(From left) Actor Michael B. Jordan, Lacy Lew Nguyen Wright, actor and founder of BLD PWR Kendrick Sampson and actor Nev Schulman at a protest in Beverly Hills on June 6. (Photo: Tommy Oliver)

Collaboration is key, and action is needed now, as protests continue in Los Angeles and across the U.S. to end systemic racism once and for all.

By Athena Mari Asklipiadis

Over the last few weeks, dozens of protests have been organized throughout Southern California following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police in Minneapolis on May 25. Attending a few Los Angeles protests, I decided to speak to some Asian American activists to discuss their experiences on the frontlines, as well as gain an understanding as to why it is important for our community join the Black Lives Matter movement.

On May 30, a Black Lives Matter march was organized to start in the Fairfax District of Los Angeles at Pan Pacific Park. After a few hours, the protest became violent when police arrived, but most media outlets that day failed to deliver accurate coverage of the events, sensationalizing the story and demonizing protestors.

Protesters supporting BLM at the Fairfax District Protest on May 30.

For nearly two hours, the march went on without incident before the arrival of the Los Angeles Police Department. Prior to the police interference, the multiracial crowd filled the park and streets, cheers erupting when cars passing by honked in support.

Residents and business owners crowded the sidewalks, watched from balconies and rooftops and cheered as the march passed. Some locals brought their own signs to join in from the sidelines, with some even bringing their children to watch the historic moment flow through the streets.

An overcome Black USPS worker wiped her tears as the crowd parted around her stopped postal truck.

Protesters thanked her for her service as they noticed her crying happy tears and chanting along.

Drivers in stopped cars not able to move through the sea of the crowd honked not out of frustration, but in solidarity. Drivers even rolled their windows down to raise a fist, with some even getting out of their cars to stand on their hoods or out of their sunroofs to cheer on the protesters.

More signs to relay powerful messages.

These images of support and solidarity were not seen in the news broadcasts that day, but rather overshadowed by the violence that ensued later in the evening.

Quickly, the peaceful march in beautiful, sunny and breezy Southern California turned aggressive and more reminiscent of a warzone than a community gathering for racial justice.

Baton-yielding police officers, agitators vandalizing police cars and buildings, tear gas, pepper spray, rubber bullets, flash bang explosions and crowds running and screaming in the streets soon became the scene at the end of the march.

It is worth mentioning that there was curiosity and shock among protesters that so many vandals videoed were white and seemingly choreographed. Rumors that Antifa, the KKK or undercover police are to blame is yet to be determined by investigators in Los Angeles.

On the ground that day was Lacy Lew Nguyen Wright, associate director of BLD PWR. BLD PWR is actor/activist Kendrick Sampson’s nonprofit initiative. You may recognize Sampson’s name or face as a major organizer and voice of the Black Lives Matter protests in Los Angeles.

Wright shared with me about the moment when the peaceful protest quickly went sour for her and her team at Third and Fairfax when the LAPD arrived to disperse the crowd. Wright explained that while she and the other protesters did not leave, they never initiated any violence.

“We never pushed back,” Wright recalled. “When we wouldn’t move, cops began swinging their batons at us and shooting rubber bullets. I was there with my boss, Kendrick Sampson, and his assistant, Mario. Mario was hit so hard on the leg that we could see his bone. A street medic came to help provide first aid, but we had to flee as the chaos broke out and get him to Urgent Care.”

Tensions started to rise when Los Angeles Police Department officers arrived on scene at the Fairfax protest.

Stories mirroring Wright’s went viral on social media that evening and in the following days.

The most disturbing accounts from the L.A. protest are those from protesters who were hit in the face by rubber bullets and those who were arrested and left in a van handcuffed for hours without access to a restroom or water.

But despite what many would consider traumatizing experiences, it only fueled protesters to continue on in the days ahead. The irony that a peaceful protest against police brutality would end in police brutality further proved the activists’ point.

One such activist is Sophie Kanno, who uses social media as her weapon in the fight to educate and activate others on this issue.

Kanno, aka @asian_soph and moderator of page @mixedpresent on Instagram, shares her thoughts daily on racial equality and the importance of solidarity during these times.

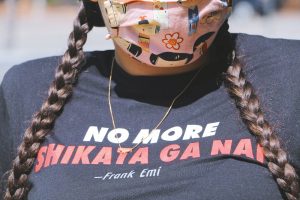

Sophie Kanno dons a kokeshi doll mask and a “No More Shikata Ga Nai” T-shirt at the Koreatown Protest on June 6.

Kanno reminds Japanese Americans that traditional sayings such as “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down” or “It can’t be helped” (shikata ga nai) have been ingrained in us for generations. Those types of phrases that echo in our minds do not motivate our community to strive for change — they only silence us.

The inaction of Asian American officer Tou Thao during Floyd’s murder proved to be an example of the common protest motto, “Silence is violence.” It’s something many Asian Americans complain is an issue in our community.

Kanno says it’s important Asian Americans have “uncomfortable conversations around race in America,” and that we should “challenge the Asian American norm of staying silent and not speaking out.”

Kanno also reminds us that during World War II, many groups stood by silently as Japanese Americans were shipped off to American concentration camps … and “even other Asian American groups were quick to distance themselves from JAs. This came as a result of fear. We were at war with Italy and Germany, too, but whiteness does not other whiteness.”

Kanno went on to say that Japanese American incarceration “was a reminder that no matter what, the Japanese were seen as foreign enemies at home, they would never be true Americans … this mind-set has not gone away, it has simply evolved.”

She added that COVID-19 resurfaced a lot of anti-Asian sentiments and proved how quickly our community could be targeted again.

“If we want other groups to stand with us when we need them to, we must stand with them when they need us,” said Kanno. “When Blacks marched and opened the door to a deeper conversation on systemic racism, they ultimately did that for all people of color. All of us — Blacks, Asians, Latinx and Indigenous peoples — have been othered for too long by whiteness and systemic racism. Enough is enough.”

Speaking to Asian Americans, Wright added, “Yes, we have our own issues. But there is no tool of oppression used on the Asian American community that wasn’t experimented on and used on Black, Brown and Indigenous communities first. They did not come up with internment camps for Japanese Americans. America already had practiced uprooting and relocating communities when they stole land from Indigenous communities.”

These histories repeating themselves to various groups in different forms over centuries bonds us against the common enemy that is White supremacy and systemic racism.

A Koreatown gathering on June 6 titled “Yellow and Brown Folks United for Black Lives” was held at Liberty Park. Various speakers spoke to their communities in their own languages to illustrate similarities between the plight of their own groups to that of the Black struggle for equality.

“Too long we have allowed animosity between our groups to perpetuate. We must build a bridge and work to understand one another, the unique struggles that we face, the similar struggles that we face and the history of our groups in this country. In doing this, true unity and solidarity will occur. A people united will never be divided,” said Kanno.

Sophie Kanno, Naomi Hayase and Athena Mari Asklipiadis participated in Loving Day outside Los Angeles’ City Hall on June 12.

The following week, on June 12,, a mixed Japanese group and festival, joined other mixed-race organizations to protest on Loving Day at Los Angeles’ City Hall.

Loving Day, founded by Japanese-Belgian New Yorker Ken Tanabe, celebrates the day interracial marriage was legalized in all 50 states on June 12, 1967, via the Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia.

Sonia Smith Kang, president of Multiracial Americans of Southern California, who was in attendance at the protest, reminded protesters that if not for various brave Black folks who fought for interracial marriage with their partners, like Mildred and Richard Loving, and if not for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many other minorities and immigrants would not have the rights they do today.

Also at the protest at City Hall was Duncan Ryuken Williams, director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture and Hapa Japan Founder.

Williams addressed the group at the protest and mentioned the intersectionalities and parallels between the shooting deaths by guards of Japanese Americans in incarceration camps during World War II to the police brutality and killings of Blacks.

Another parallelism between WWII and today’s events was the presence and support of the Quakers, who joined the crowd at City Hall chanting “Black Lives Matter.”

During WWII, the “Religious Society of Friends” (also known as Quakers) utilized their American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) to provide support to Japanese Americans during and after their forced incarceration.

‘All of us — Blacks, Asians, Latinx, and Indigenous peoples — have been othered for too long by whiteness and systemic racism. Enough is enough.’

— Activist Sophie Kanno

Many JAs may remember that Quakers provided water and aid as JAs were boarding trains leaving to the American concentration camps, as well as gave JA children gifts during the holidays.

Additionally, their support after WWII was instrumental, as Quakers assisted many JA families with resettlement and housing following their release. Seeing a new generation from the same loyal group 75 years later in solidarity chanting next to descendants of those who were wrongly incarcerated was touching, but sadly, it was also proof that we are still fighting the same injustices in our country today as we were then.

Wright reminds us that protests and words alone mean nothing if not moved into action.

“A protest is a great first step in getting involved in activism, but after that, the real work begins,” she said.

And by “work,” Wright means supporting Black businesses, hiring diverse employees and assisting in the movement.

“Find the places you hold power, and use that power for racial equity,” she said. “That can be at your jobs, at your schools, in your homes, at the voting booth.”

On June 20, Nikkei Progressives, a “grassroots, all-volunteer, multigenerational community organization,” released a video voiced by multiple Japanese Americans outlining the course of actions they plan to take to support Black Lives Matter.

Nikkei Progressives also encouraged the JA community at large to 1) Donate to Black Lives Matter — LA and the Movement for Black Lives, 2) Contact L.A. City Council to support the People’s Budget, 3) Educate ourselves on how to challenge and dismantle racism and engage in dialogue to combat anti-blackness.

Nikkei Progressives is one of several Japanese American groups doing something to become a better ally to the Black community. Tsuru for Solidarity and Japanese Americans for Justice also making a difference.

Wright clarified the role of being a true ally: “I am not here to ‘help’ the Black community. They don’t need our help. They need our collaboration. We all need to be in this work together if we want to dismantle the systems that oppress all of us. We must do this work together because all of our oppression and liberation is tied together. In the words of Lilla Watson, ‘If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.’”

Athena Mari Asklipiadis, a hapa Japanese L.A. native, is the founder of Mixed Marrow, a filmmaker and a diversity advocate.