A group photo from the 88th and 60th birthday celebrations of Dr. William Higuchi and Shirley Ann Higuchi, respectively, at the Grand America Hotel in Salt Lake City. Pictured (seated) are Shirley Ann Higuchi and Dr. William Higuchi and (front row, from left) Bill Collier, Angie Collier, Nan Kline, Amelia Collier, Adele Collier, Theresa Bruce, Dr. Jeanette Misaka, Consul General Midori Takeuchi, Hon. Judge Raymond Uno, Hanako Wakatsuki, Yoshiko Uno, Vanessa Yuille, Janis Seils, Emily Higuchi, Pat Higuchi, Jim Higuchi, Kathy Yuille, Mia Russell and (back row, from left) Derek Dodd, David Bruce, Lucas Yuille, Kevin Yuille, Katrina Yuille, Ray Locker, Danielle Laufer, Mike Holland, Rex Seils, David Ono, Becky Higuchi, Bob Higuchi and Julie Abo. (Photo: Brian Smyer)

Highly successful former classmates who were incarcerated together in Heart Mountain during World War II reunite to celebrate the 88th birthday of one of their own.

By Ray Locker, Special Contributor

Jeanette Misaka didn’t know William Higuchi while they were in the same grade in school at the Heart Mountain War Relocation Center, but she knew his reputation.

“He was the brains,” she said.

Those brains helped Higuchi, now 88, earn a doctorate in pharmaceutical sciences and teach at the universities of Michigan and Utah, where he led the pharmaceutical sciences department for 30 years. His contributions to science led the government of Japan to award him its Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon, in 2012.

Higuchi was the first of a trio of former classmates at Heart Mountain to receive one of the variations of the Order of the Rising Sun. Misaka, a Ph.D. in special education and emeritus professor at the University of Utah, received the honor citation in 2016. Raymond Uno, the first Asian American judge in Utah, received his in 2014.

Heart Mountain former child incarcerees and classmates Dr. Jeanette Misaka and Honorable Judge Raymond Uno (pictured together, far right) reunited in Salt Lake City to celebrate the 88th birthday of fellow Heart Mountain classmate Dr. William Higuchi and the 60th birthday of his daughter, Shirley Ann Higuchi (pictured together, far left).(Photo: Brian Smyer)

All three now live in Salt Lake City, where they gathered on March 16 at the Grand America Hotel for a birthday celebration for Higuchi and his daughter, Shirley, who turned 60 that day. Shirley Higuchi is an attorney for the American Psychological Association in Washington and chair of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, which operates an interpretive center on the site of the former Japanese American concentration camp during World War II.

Together, Higuchi, Misaka and Uno share a traumatic wartime history that saw their families uprooted from comfortable lives in California before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

Higuchi lived with his parents, three brothers and younger sister, Emily, on a 14.25-acre farm in San Jose, Calif., in what is now the heart of Silicon Valley. Misaka and her three sisters also lived in that area, where her father, Henry Mitarai, was a farmer who pioneered the use of mechanized farm equipment. Uno was born in Ogden, Utah, but moved to Southern California’s San Gabriel Valley with his family in 1937.

All of the families lost their livelihoods after the outbreak of the war when they and 120,000 Japanese Americans were forced from their homes and businesses and sent to one of 10 concentration camps from California to Arkansas. Their families were first sent to assembly centers at the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds in Pomona, Calif., or Santa Anita Park horseracing track in Arcadia, Calif., before they arrived at Heart Mountain in northwestern Wyoming in the summer and fall of 1942.

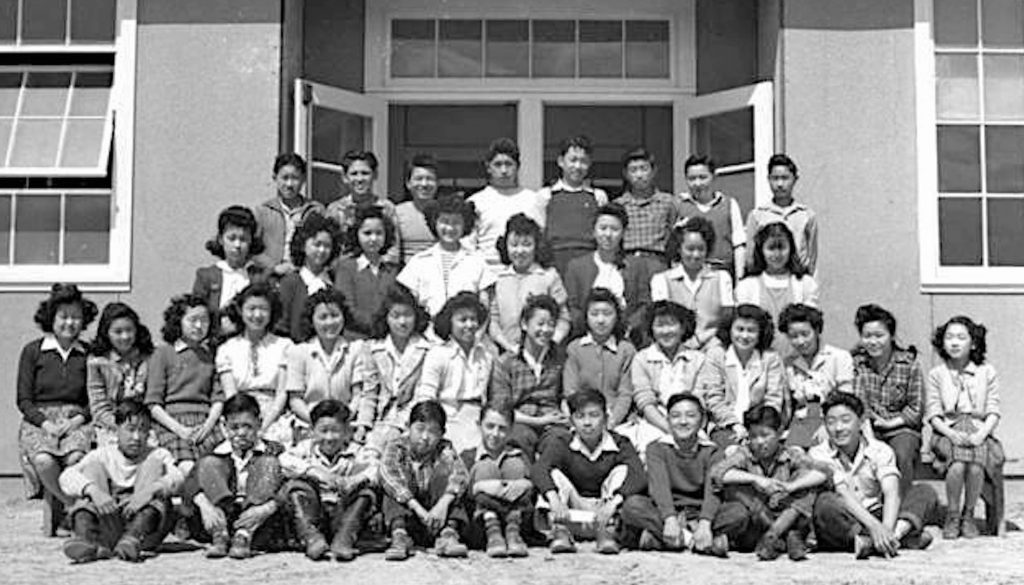

A photograph of an eighth-grade class at Heart Mountain High School for the yearbook, taken at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center. The Hon. Judge Raymond Uno is seated in the front row (far right). Also pictured is Dr. William Higuchi’s future wife, Setsuko Saito (second row, fourth from left) (Photo courtesy of the Higuchi Family)

The three classmates, as well as Higuchi’s late wife, Setsuko Saito Higuchi, who Misaka knew well at camp, helped build the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation and push for the creation of the award-winning museum there.

Setsuko Higuchi was also a fellow classmate. She met her future husband in class, and an exhibit in the Heart Mountain museum shows the two seated next to each other in their ninth-grade class photo.

William Higuchi

When the war broke out, two of the older Higuchi brothers, James and Takeru, were grown and living elsewhere. James was a doctor in the Army, while Takeru was studying for his doctorate in pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Wisconsin. Kiyoshi, the second brother, remained in San Jose; his education had been slowed by a four-year bout with pleurisy.

The Higuchi family was forced to sell their farm to a neighboring family at a significant loss before they went to the assembly center at Santa Anita Park and then to Heart Mountain in September 1942. Iyekichi Higuchi, who had immigrated to the United States in 1915, thought he was having a heart attack upon the family’s arrival at Heart Mountain. Doctors at the rudimentary hospital determined it was a gastrointestinal disorder.

While at camp, William Higuchi excelled at school. He and Setsuko Saito were ranked in the A class of students, which had high-achieving students from across the West Coast who had been forcibly yanked from their schools.

At the end of WWII, Iyekichi suffered a heart attack just days before he was set to return to San Jose to find a new home and farm. He recovered, and by 1946, the family bought a new farm in San Jose.

William Higuchi went on to graduate school at the University of California, Berkeley, where he bumped into his former classmate, Setsuko Saito, while walking near one of the campus tennis courts — the couple was married in 1956.

He held teaching jobs at the University of Wisconsin and worked in private industry before joining the University of Michigan faculty in 1962, remaining for 20 years.

In 1982, William Higuchi joined the University of Utah faculty and guided dozens of Japanese students through their work in pharmaceutical sciences. There, he co-founded three pharmaceutical companies — TheraTech, Lipocine and Aciont. Lipocine (LPCN) is traded on the Nasdaq exchange.

The Japanese government awarded him the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon, in 2012 for his contributions to pharmaceutical education in Japan through his work at the University of Michigan and University of Utah.

“It was a great honor to receive the award,” William Higuchi said. “I only wish my wife was there to see it because she wanted so much for it to happen.” Setsuko Higuchi died in 2005.

Jeanette Misaka

Henry Mitarai, Jeanette Misaka’s father, moved from Heart Mountain in 1943. Two of his business partners in California had found land that Mitarai could farm in Sigurd, Utah. He left his wife and four daughters in Heart Mountain until the following spring, when they all joined him on the new farm.

Jeanette Misaka said she was nervous about being the only Japanese American in her new high school, but her mother would not allow her to stay home. On her first day at school, the principal held a school assembly in which he announced, “We have a new student. She’s an American, just like you.”

Misaka attended the University of Utah and then started teaching at local schools before joining the University of Utah faculty, where she is an emeritus clinical professor in the department of special education.

She met her future husband, Tatsumi “Tats” Misaka, after he returned from the Korean War in the 1950s. He was the brother of University of Utah basketball star Wat Misaka, who was the first nonwhite player in what became the National Basketball Assn.

Misaka received the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Rays, in 2016 for her leadership in the Japanese American Citizens League and keeping alive the memory of the Japanese American incarceration.

Raymond Uno

Along with his parents, brother and sister, Raymond Uno was forced from his home in California and sent first to Pomona and then Heart Mountain in 1942. His father, Clarence, had immigrated to the United States and then served in World War I in the Army’s Rainbow Division in France. Although U.S. law then prohibited first-generation Japanese immigrants from becoming citizens, Clarence Uno earned his citizenship through a special law passed in 1935.

Two-thirds of the Japanese Americans incarcerated during the war were U.S. citizens. Few, however, were veterans like Clarence Uno, who died in January 1943 after attending a USO meeting in camp to discuss how to help U.S. troops serving overseas.

After Clarence’s death, the Uno family returned to Ogden, where Raymond finished high school, worked on the railroads during the summer and then entered the Army. He served in intelligence units in Japan during the Korean War.

Raymond Uno earned a law degree and eventually became the first Japanese American judge in the state after having previously serving as a referee of the juvenile court, deputy Salt Lake County attorney, assistant attorney general of Utah and a private practice lawyer. He became president of the JACL in 1970 and pushed for the payment of reparations to those incarcerated during WWII. Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act that provided such payments in 1988, which President Ronald Reagan then signed into law.

Uno received the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette, in 2014 for his work with the JACL and for supporting the Japanese American community in Utah and throughout the nation.

“The three of us were given the Japanese Foreign Minister’s Commendation, and the three of us were given the Order of Rising Sun,” Uno said of his fellow classmates. “That’s three of us in the same class, in Salt Lake City. I don’t think that’s happened in any other camp.”

Shirley Higuchi, who is currently writing a book about the incarceration, uncovered many of the details of her family’s incarceration and their relationships with Misaka and Uno that were never shared with her as a child.

“It’s testament to their dedication and commitment that they accomplished so much to merit receiving this award,” she said.

Ray Locker is an author and freelance writer living in Washington, D.C.