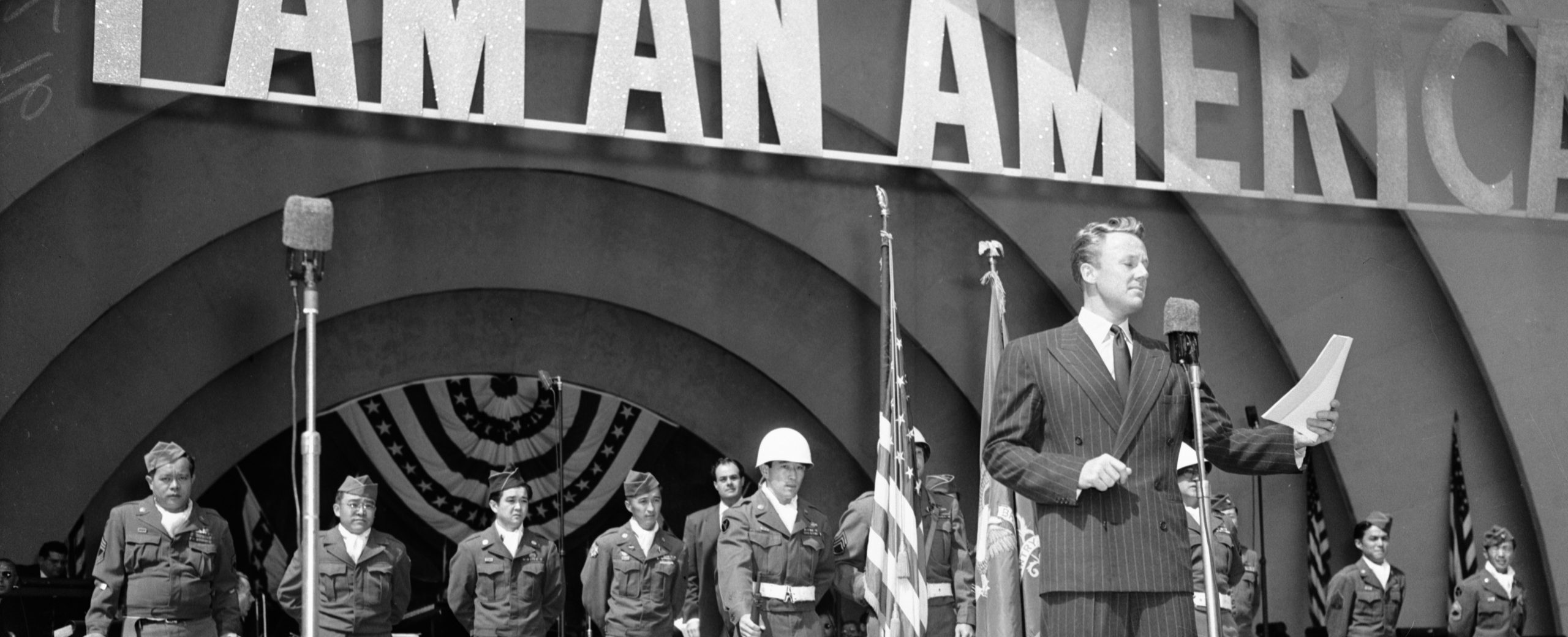

“Go for Broke!” star Van Johnson introduces several Nisei WWII veterans at the Hollywood Bowl at the May 20, 1951, I Am an American Day. Frank Fujino stands at the far left of the photo. (Photo: Copyright © 2020 USC Digital Library. Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection. Used with permission. May not be reproduced without permission of USC Digital Library.)

An uncanny coincidence leads to a puzzling story of a 442 veteran.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor, Digital and Social Media

[Editor’s Note: The following is Parts I and II of Finding Frank Fujino. Part I was published in the Nov. 6-19, 2020, issue of the Pacific Citizen. Part II was published in the Dec. 18, 2020 Holiday Issue of Pacific Citizen.]

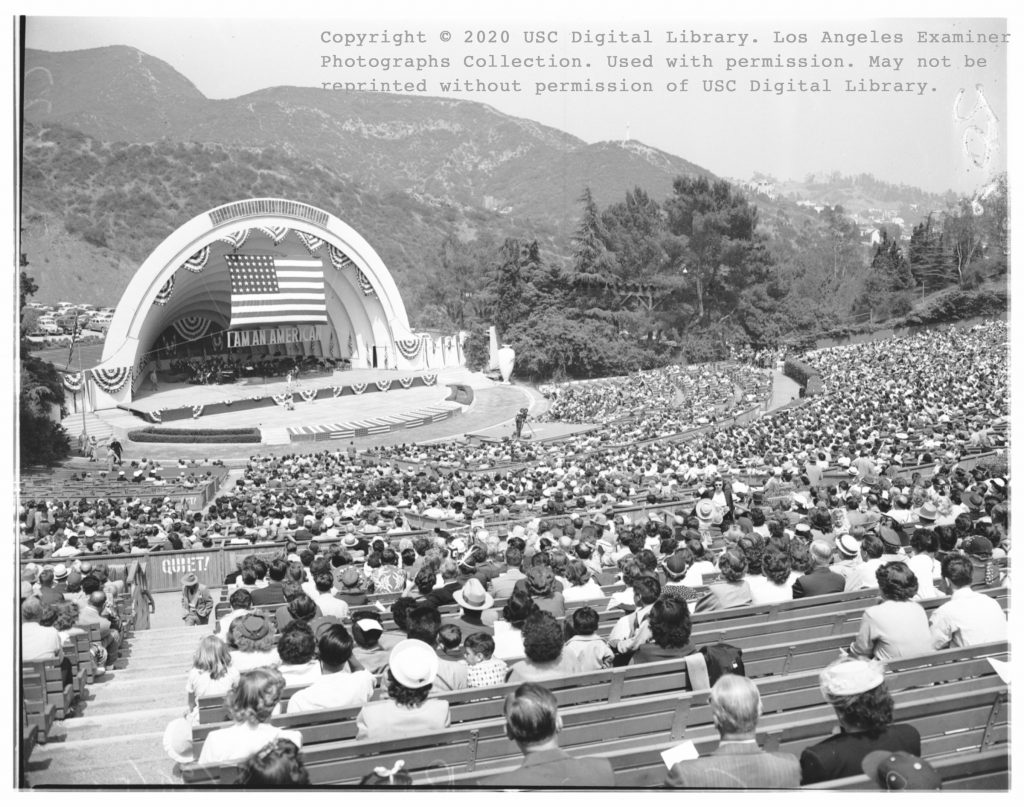

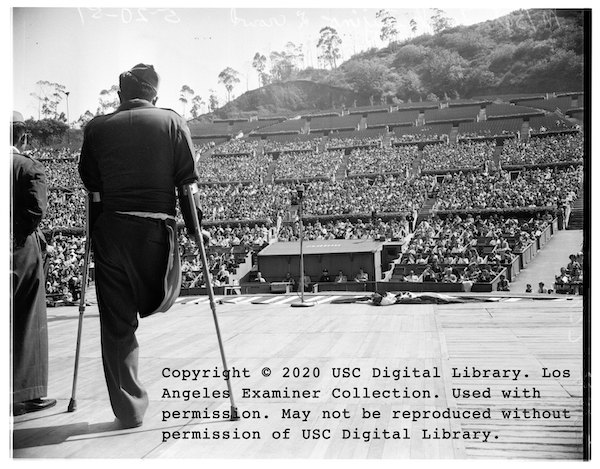

On Sunday, May 20, 1951, 17,500 people gathered at the Hollywood Bowl in sunny Southern California for “I Am an American Day,” a two-hour extravaganza of patriotism and welcome for newly naturalized U.S. citizens that featured some of the most-popular entertainers and celebrities of the day.

Overview of the Hollywood Bowl at I Am an American Day, May 20, 1951 (Photo: Copyright © 2020 USC Digital Library. Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection. Used with permission. May not be reprinted without permission of USC Digital Library.)

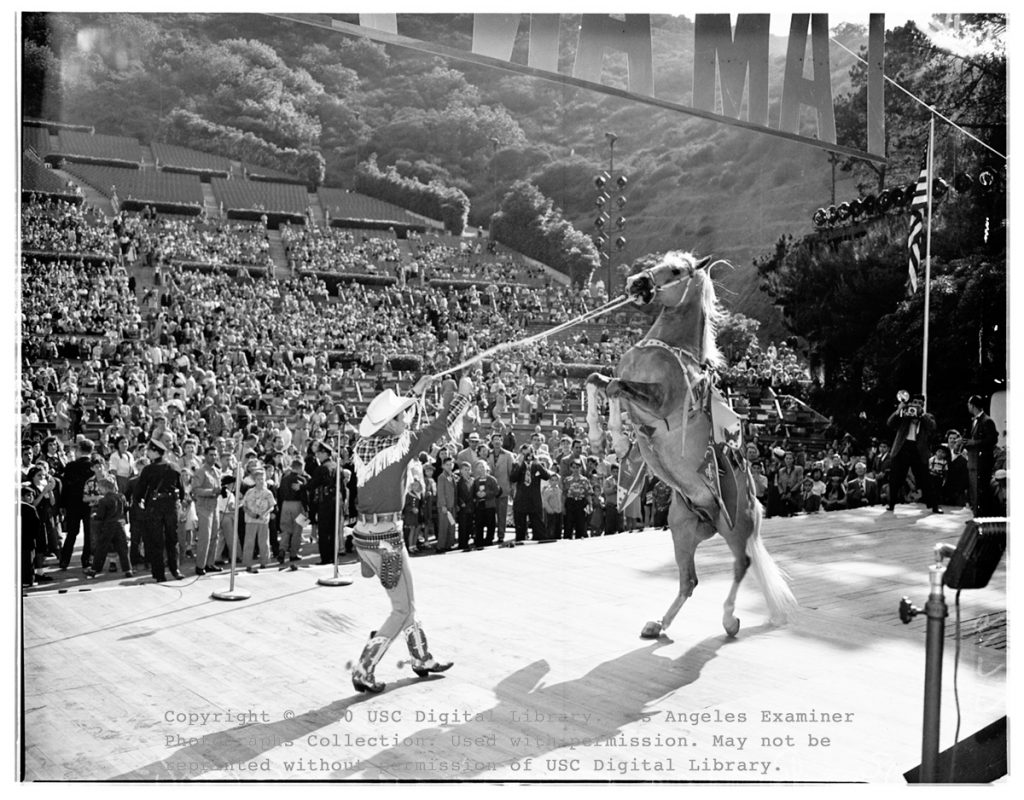

On stage that Sunday were some notable stars still remembered today: singing cowboy Roy Rogers and his trusty mount, Trigger; comedic duo Gracie Allen and George Burns; and actors Lana Turner, Donald O’Connor, Gene Nelson and future star of “The Munsters,” Yvonne De Carlo.

Singing cowboy Roy Rogers and his horse, Trigger, were among the entertainers at the Los Angeles edition of I Am an American Day on May 20, 1951. (Photo: Copyright © 2020 USC Digital Library. Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection. Used with permission. May not be reprinted without permission of USC Digital Library.)

Also present were acting (and future) California Gov. Goodwin Knight and American Legion National Commander Erle Cocke Jr., who retired as a brigadier general. The master of ceremonies was the “toastmaster general of the United States,” George Jessel.

The Los Angeles Examiner, owned by infamous newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, would give the event front-page coverage, just below a banner headline that read “FRESH RED DIVISIONS HIT ALLIES,” a reference to the in-progress “police action” better known as the Korean War.

The next day’s front-page coverage was because the Examiner sponsored the event. In 1939, after Hearst learned of a local I Am an American Day event in one of his newspapers, he used the power of his newspaper empire to advocate that it be celebrated across the land.

On May 3, 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt inked a joint congressional resolution to proclaim that it would be marked annually on the third Sunday of every May as a day for the “recognition, observance and commemoration of American citizenship.”

The ironies of Hearst and Roosevelt helping to set aside a day to commemorate American citizenship are manifold.

The Hearst newspapers were notorious during this era not just for sensational “yellow journalism,” but also for “yellow peril journalism” in general and, before and during World War II — along with the then-reactionary Los Angeles Times — anti-Japanese and anti-Japanese American rhetoric.

Roosevelt, meantime, despite having just proclaimed a day that celebrated American citizenship in 1940, issued Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, which paved the way to putting ethnic Japanese — the majority of whom were American citizens — into several government-operated concentration camps.

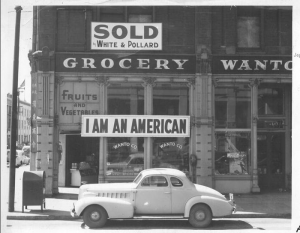

More irony: The name of the event may today be best-remembered tangentially as appearing in a Dorothea Lange photo, taken in Oakland, Calif., in March 1942 of the Wanto Co. grocery storefront and its sign — a cri de coeur, really — that read “I AM AN AMERICAN,” placed, presumably, by the Japanese American owner.

Dorothea Lange’s 1942 photo shows a sign identical to the one used at the 1951 I Am an American Day.

The sign uses a typeface and style — all uppercase letters — identical to the even larger sign used more than nine years later at the Hollywood Bowl.

Unbeknownst to all gathered, the May 20, 1951, gala would be the final national recognition of I Am an American Day.

Whether there was a connection between the death of Hearst on Aug. 14, 1951, and the demise of the event is unclear, but in February 1952, President Harry S. Truman signed a bill that not only moved it to Sept. 17 to commemorate the signing of the Constitution on that same day in 1787, it was also renamed “Citizenship Day.”

In 2004, it officially became known as “Constitution Day,” even though Sept. 17 is now still commonly referred to as both “Citizenship Day” and “Constitution Day.”

❖❖❖

The year 1951 was also when the MGM movie studio released “Go for Broke!” the first and to this day still only motion picture by a major Hollywood studio that attempted to tell the story of the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team, the segregated Army regiment that, with the exception of most of its officers, were Japanese Americans who fought in WWII with astonishing valor and distinction in the European Theater.

In a confluence of patriotism and movie-marketing synergy, “Go for Broke!” star Van Johnson, backed by several uniformed Japanese American veterans of the 442nd, appeared on the Hollywood Bowl stage at the I Am an American Day event to promote the movie.

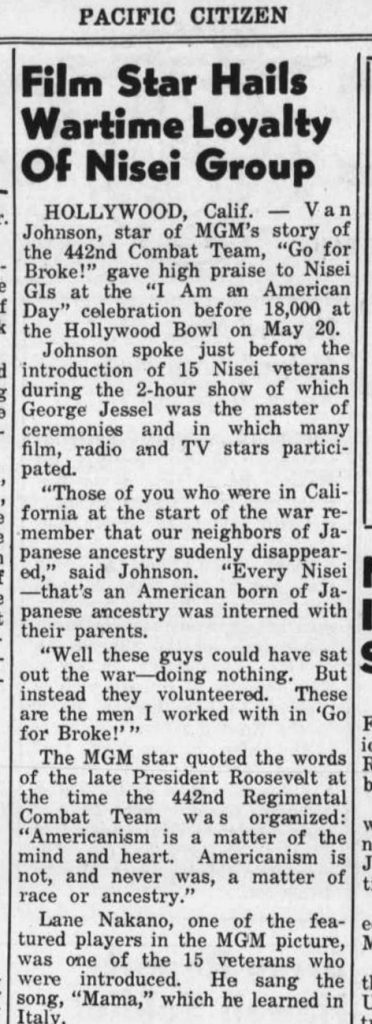

The P.C.’s May 26, 1951, story about I Am an American Day

This was noted in a Pacific Citizen newspaper article from the May 26, 1951, issue. In part, it read: “Those of you who were in California at the start of the war remember that our neighbors of Japanese ancestry suddenly disappeared,” said Johnson. “Every Nisei — that’s an American born of Japanese ancestry — was interned with their parents.

“Well, these guys could have sat out the war — doing nothing. But instead, they volunteered. These are the men I worked with in ‘Go for Broke!’”

The Pacific Citizen newspaper’s coverage of this final I Am an American Day concluded: “The MGM star quoted the words of the late President Roosevelt at the time the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was organized: ‘Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart. Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry.’ ”

Unknown is whether any of the Japanese American veterans found Roosevelt’s words ironic. What is known is that the Nisei veteran lined up behind Johnson, to his far right, was Frank Toichi Fujino.

And just who was Frank Fujino?

❖❖❖

That was a question I had wondered about since 2013, when I bought the Culver City, Calif., house he used to own.

Frank Fujino’s license plate with a sticker for 1983, the year he died.

I knew Fujino was a second-generation Japanese American. I learned that from his daughter’s real estate agent when I went to an open house and saw in the garage an outdated California license plate with a 1983 registration sticker nailed onto a work cabinet, held in place by a license plate frame that read “100/442 RCT” across the top and “Go for Broke” across the bottom.

Having made a short documentary about the 100th/442nd, I knew the significance of the license plate holder — and as it would turn out, it was one of the things that helped my family and me buy this house instead of a couple of house flippers. (See page 28, Dec. 13, 2013, Pacific Citizen Holiday Special Issue.)

Curious to learn more about Fujino, I did some cursory internet research on him at the time, but the only significant item I found was a photograph in the Japanese American National Museum’s website.

It pictured a group of middle-aged Nisei military veterans circa 1970. Many were wearing garrison caps showing their affiliations with the American Legion, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Disabled American Veterans, etc. They had raised money and donated wheelchairs to the Keiro retirement home.

In 1970, several Nisei vets donated wheelchairs to the Keiro retirement home. Fujino is third from right. (Photo: Japanese American National Museum. Photo by Toyo Miyatake studio, gift of the Alan Miyatake family.)

Among them, in the background, stood Fujino, third from the right. At least I now had a face for the name, and I left it at that.

Fast-forward to last fall.

I tried another internet search to glean what might have been added over the intervening years about Fujino, using some different search terms. What Google came back with stunned me.

Among the images from the 1951 I Am an American Day at the Hollywood Bowl is one taken from the rear of the stage.

In it is a man whose back is to the camera. He faces the audience. He is on crutches.

His right leg is gone.

Frank Fujino faces the audience gathered at the Hollywood Bowl on May 20, 1951, on the final I Am an American Day. (Photo: Copyright © 2020 USC Digital Library. Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection.)

It was Frank Fujino, the former owner of the house I’m now making payments on. Suddenly, several things made sense. The wheelchair ramp to the backdoor that we removed. The grab bar outside the kitchen door. The issues of DAV Magazine that still arrive in the mail to his late widow, Yuriko Fujino.

More internet searches yielded additional tidbits. One, in particular, would stun me yet again, namely a footnote on page 395 of James C. McNaughton’s 2006 book “Nisei Linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service During World War II.”

In part, it read: Another Nisei, Frank Fujino, was said to have been captured on Bataan but escaped and later joined the 442nd RCT. “Nisei Survived Death March on Bataan, Lost a Leg in Rescue of Lost Battalion,” Pacific Citizen, 29 Mar 47, p. 1.

I immediately grabbed the bound edition for 1947 from the Pacific Citizen’s office’s bookshelf. Sure enough, there was the story — and what a story! (Note: The scan and the text of the original article that appeared in the March 29, 1947, P.C. can be read here.)

In a way, the introduction to the P.C. article said it all.

Ed. Note — The story of Frank Fujino, who survived the Death March on Bataan and escaped from a Japanese prison ship and later lost a leg during the 442nd Combat Team’s rescue of the Lost Battalion, is a true story which reads like a dime thriller. The experiences of this California Nisei GI make one of the most dramatic sagas to come out of World War II.

It was written by John Kitasako and had a Washington dateline. If one word were to encapsulate the story, it would be “fantastic.”

❖❖❖

Here are some facts about Frank Fujino. He was born in Fullerton, Calif., on Sept. 13, 1918, to Japan-born Issei parents, Tomo and Tojiro Fujino, and he died on Aug. 16, 1983 at Brotman Hospital (now Southern California Hospital at Culver City).

According to the 1930 Census, taken when Frank Fujino was 11, he had an older sister, Kaoru, 13; two younger sisters, Tomiyo, 9, and Mitsuyo, 7; and a younger brother, Yeiji, 6.

Fujino’s date of enlistment in the Army was June 25, 1941, and he was honorably discharged on April 17, 1947, with the rank of private first class.

He served in K Co. of the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team. His military serial number was 39160647. He was wounded in November 1944 and eventually lost his right leg; he spent time recuperating at the Walter Reed General Hospital.

This photo, from Wilson Makabe, shows several 442 vets at Walter Reed General Hospital in July 1946. Clockwise are Makabe, Rom Harimoto, Frank Fujino, on bed, Terumi Kato, in wheelchair, and George Miki, eating manju. (Photo: Courtesy of the National Japanese American Historical Society.)

That preceding is verifiable and true. But some of the other elements in the 1947 article? Let’s just say there are some questions.

His entire family killed in a car accident at age 8? Adopted by the O’Connor family of La Cañada, Calif.? Attended both Stanford and UCLA? Was stationed in the Philippines when the Japanese invaded on Dec. 8, 1941? Survived the Bataan Death March? Escaped from a torpedoed POW ship bound for Kobe? Made his way to the inland “American base at Delmonico”? (There was no such base; there was, however, a Del Monte Airfield.) Fled on the last plane to leave, only to be forced by a Japanese Zero to land on an island and rescued by an “Allied submarine and brought to Australia”? Applied to two different officers training schools, only to be rejected because of his ethnicity? Awarded the Silver Star?

It is, in a word, fantastic.

For example, Fujino’s parents, Tomo and Tojiro Fujino, are named in the War Relocation Authority’s Final Accountability Roster, which means they (and his siblings) were incarcerated at Arkansas’ Jerome and Rohwer camps and were not killed in an automobile accident when he was 8.

If there is the possibility that Fujino was indeed put up for adoption by his parents for any reason, resulting with him being adopted by the Thomas O’Connor family of La Cañada and becoming Frank Fujino O’Connor, adoption records are inaccessible except by family members.

As for being stationed in the Philippines when the Japanese invaded on Dec. 8, 1941, Fujino was indeed active duty, having entered the military on June 25, 1941. But as this composite image of where he had been transferred prior to joining the 100th/442nd shows, he was not in the Philippines. Also, the timeline of entering the military in late June 1941 and being sent to the Philippines by the Dec. 8, 1941, Japanese invasion is, though possible, not probable.

That would mean the exploits noted in the 1947 P.C. article, including surviving the Bataan Death March, could not have happened.

According to historian and researcher Seiki Oshiro, who has spent the last several years compiling a registry of Nisei who served in the Military Intelligence Service during WWII and is also knowledgeable about the service of all Nisei veterans during that war, there were only four Nisei in the Philippines prior to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor and its invasion of the Philippines.

They were Richard Sakakida, Arthur Komori, Clarence Yamagata and Yoshikazu Yamada. In an email, Oshiro added, “There is no evidence for Fujino to be the fifth!”

I sought out as many old-timers as possible who might still remember Fujino, who would be 102 now. No one, it seemed, remembered him. Three fellow 442 vets I sought out had no memory of him. Two — Lawson Sakai and Don Seki — died in 2020, both at 96.

❖❖❖

Although Frank Fujino is a 442 vet who until now was mostly forgotten, he appears several times in different Japanese American community publications of yesteryear. He also received coverage in mainstream newspapers and other media.

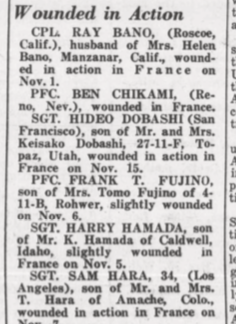

Before Fujino’s story was told in the March 29, 1947, Pacific Citizen, his name appears in the Dec. 16, 1944, P.C. in a front-page article.

Its headline reads, “Ten Western Nisei Killed on French Front,” followed by a subheadline that reads, “34 Others Wounded, Two Missing in Action in Europe.”

The article’s first two paragraphs read: “Ten American soldiers of Japanese ancestry were killed, 34 others were wounded and two are missing in action in eastern France, according to word received by next of kin in the western United States.

“The following list is unofficial and is compiled by the Pacific Citizen from information from next of kin and from relocation centers.”

Detail from a P.C. article dated Dec. 16, 1944.

Among those listed as wounded in action, between Hideo Dobashi and Harry Hamada, is the report for Fujino. It reads: “PFC. FRANK T. FUJINO, son of Mrs. Tomo Fujino of 4-11-B, Rohwer, slightly wounded on Nov. 6.”

In a report that predates the P.C.’s article, the Dec. 6, 1944, Rohwer Outpost camp newspaper also reports that Fujino had been wounded. That snippet reads: “On Nov. 6, Pfc. Frank T. Fujino received slight wounds. His mother, Mrs. Tomo Fujino, lives in 4-11-B.”

Fujino is also mentioned in the Dec. 14, 1944, McGehee Times newspaper (McGehee is a town a few miles from the Rohwer WRA Center) in an article with the headline, “21 War Casualties From Rohwer Center Reported in 3 Weeks.” His entry in that article reads: “Pvt. Frank T. Fujino, son of Mr. and Mrs. Tojiro Fujino.”

From these three articles, it’s apparent that Frank Fujino’s parents were not killed in a car accident when he was 8, as reported in the March 29, 1947, P.C. article.

Both the Rohwer Outpost and Pacific Citizen reported that his wounds were “slight.” But since Fujino lost his right leg, the reports that his wounds were “slight” seem incongruous.

It’s possible that the initial injury reported in both papers was inaccurate. It’s also possible that even if the injury report was accurate, unsanitary conditions, as was alluded to in the March 29, 1947, P.C. article, caused an infection or infections. (Unclear in the article, however, is when his right leg was amputated: in the field or while hospitalized.)

In Ancestry.com’s hospital admission card for Fujino, it indicates under second diagnosis, “Gangrene, not elsewhere classified.” If accurate, that would seem to corroborate a severe infection could have led to amputation. In the same section, however, under Third Diagnosis, it reads: “Osteomyelitis (secondary to traumatism) Causative Agent: Artillery Shell, Fragments, Afoot or unspecified” (sic)

Again, if accurate, that would indicate Fujino was hurt by artillery fragments, the severity of which is unclear.

Osteomyelitis, incidentally, is an infection of the bone. And, in the same document, under Medical Treatment, it reads: “Fracture, compound, closed, treatment with skeletal traction (includes Kirschner Wire).”

For those who have forgotten their basic first aid, a compound fracture is when a broken bone breaks through the skin, a description that sounds far more serious than “slight.”

(To muddy the waters even further, the Ancestry.com document lists an admission date of November 1944 and a discharge date of April 1944, which makes no sense.)

Going back to the date of Fujino’s injury, the March 29, 1947, P.C. article reported that Fujino’s injury occurred during the Rescue of the Lost Battalion. According to Densho.org and GoForBroke.org, however, that exploit took place between Oct. 25 and Oct. 30. In other words, the reported date of Fujino’s injury happened after the Rescue of the Lost Battalion.

Also prior to Frank Fujino/Frank Fujino O’Connor’s appearance in the March 29, 1947, P.C., he appears on page 1 of the Oct. 30, 1946, Daily Tar Heel, the newspaper of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It’s a wire story from UP Feature Services.

In it, some of what was later related in the March 29, 1947, P.C. appears here: the Frank Fujino O’Connor moniker, both parents no longer living, attending Stanford (no mention of UCLA, though), joining the Army in 1938, being stationed in the Philippines, being “evacuated on the last transport to leave the Philippines,” later joining the 442nd and losing his leg in the Rescue of the Lost Battalion. (The article writes “ … when they took him to the hospital the doctors decided to amputate a leg.”)

Missing from the Daily Tar Heel article is surviving the Bataan Death March and escaping from a Japanese prisoner of war transport that gets torpedoed by a submarine. New, however, are the reports of going home on furlough to Pasadena, Calif., to visit his foster parents. While “home,” he attempts to get a haircut, only to get “thrown out of 23 barber shops.”

The story’s last paragraph reads: “Frank tried eleven other barbershops around his home. One threw his crutches out of the shop, and then stood glaring as the one-legged sergeant hobbled out. None of the barbershops seemed to care that Frank was wearing three rows of service ribbons on his uniform. None of them noticed that one of the ribbons was the Silver Star.”

Some of that same reporting appears in the March 6, 1947, edition of the Hawaii Star newspaper. Its headline reads, “Nisei Veteran Help Fight For Democracy; Finds Little Left in California Hometown.” It appears to be a rewrite* of the same story that appeared in the Daily Tar Heel, but its first paragraph contains an undated attribution to a story that appeared in the Los Angeles Daily News.

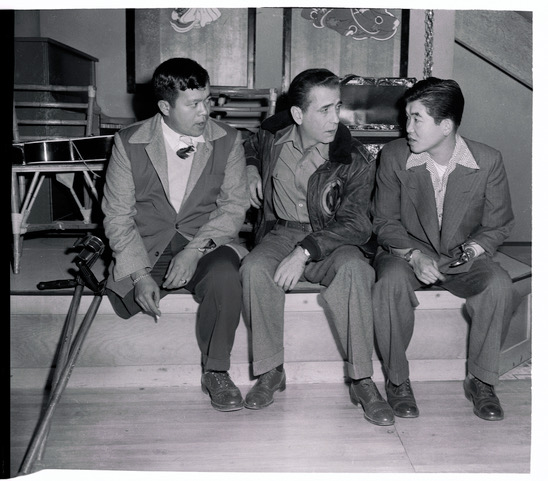

In this photo by Toge Fujihira from the P.C.’s Dec. 8, 1945, issue, Frank Fujino is on the left, seated at a table with his friend and Walter Reed roommate, Terumi ”Terry” Kato and another unidentified 442 vet at the Hotel Delmonico. Standing are Earl Finch and Ed Sullivan. According to the photo caption, the Nov. 21 event was a New York JACL dance.

It also turns out that Fujino again appeared in the P.C. before the March 29, 1947, article. In the Dec. 8, 1945, P.C. is a stand-alone photo with a headline and caption. Its headline reads, “Combat Buddies Meet at JACL Dance.” In the photo, credited to Toge Fujihira, are, from left, Frank Fujino, noted 442nd RCT benefactor Earl Finch and fellow amputee Terumi “Terry” Kato, who is talking to a third unidentified 442 vet whose face is obscured.

The Nisei are all in their Army uniforms. On the left arm of the jacket worn by the unidentified soldier is the iconic 442 emblem of a hand holding aloft the torch of liberty.

Standing to the far right is someone who would later go on to become famous for introducing America to Elvis Presley, the Beatles and Topo Gigio, a man who is identified as a “famous Broadway columnist”: Ed Sullivan.

Fujino also appears in a photo that was part of the Los Angeles Examiner’s I Am an American Day coverage from that paper’s May 21, 1951, edition. In it, “Go for Broke!” star Van Johnson kneels next to Fujino, in uniform, seated in a folding chair with his crutches in his lap, with comedian George Jessel leaning over Fujino.

“Go for Broke!” star Van Johnson chats with Frank Fujino and comedian George Jessel in this photo that originally appeared in the May 21, 1951, Los Angeles Examiner’s coverage of the I Am an American day festivities that took place at the Hollywood Bowl. (Photo: Copyright © 2020 USC Digital Library, Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection. Used with permission. May not be reprinted without permission of USC Digital Library.)

Worth noting is that in the photo, Fujino’s chevrons show his rank is that of master sergeant. That would indicate that Fujino had been promoted from his rank of private first class as shown in his Enlisted Record and Report of Separation Honorable Discharge document dated April 17, 1947, obtained from the National Personnel Records Center.

The long-defunct magazine Scene, which might be described as a People magazine focused on the Nisei population, ran a feature on Fujino in its December 1954 issue.

The article is about the recognition given by the Disabled American Veterans to Fujino for his “exceptional and meritorious conduct in performance of outstanding service” as a DAV national service officer for the Los Angeles area.

This article is interesting because it describes how he was injured as he served in the 442nd.

Fujino’s war injuries are considerable. (He becomes literally speechless when he gets a slight cold or passes through a high altitude, result of a throat wound.) In a battle action in France, in Bruyeres, he was declared dead by the burial squad, loaded on a jeep wagon with the other dead. (He was on the bottom.) Chaplain Hiro Higuchi (now of Hawaii) checked him for his “dogtag” (identification plate), noticed Frank was breathing. He was rushed to the hospital and put in an iron lung.

For his fighting that day, a heroic adherence to his mission in spite of his wound, Fujino won the Silver Star, received the award from President Truman.

This undated photo, which appeared in Scene magazine and the Rafu Shimpo, shows Frank Fujino shaking hands with President Harry Truman while Fujino was hospitalized at Walter Reed.

The article, which contains a photo of Truman meeting Fujino at Walter Reed Army Hospital, is also notable because it details his role in the formation of the Nisei 100 DAV chapter, of which he served as its first commander. (Nisei 100 is now defunct, having been absorbed by another Los Angeles area DAV chapter.) The article also includes a photo of Frank Fujino’s wife, Yuriko, and young son, Arnold Terry Fujino, at play in their yard.

The Scene article also reports on what Fujino had to do to become a DAV NSO, namely put in “2 years of medical education, 2 years of law and 2 years of Veteran Administration Law.”

The same photo of Truman and Fujino also appeared in an article by Henry Mori in the Oct. 25, 1949, Rafu Shimpo newspaper. In it, we get a physical description of Fujino as a “solid-built guy who must weigh at least 175 pounds, and you’d immediately think he was a football player coming off the field.”

Mori’s article continues: “He is the eldest son of Mr. and Mrs. Tojiro Fujino who hail from Fukuoka, Japan. He has two sisters, and a younger brother.” This description stands in contrast to the P.C. article that claimed he had been orphaned at 8 because of an automobile accident and was the only surviving family member.

The article also reports that Fujino was “hit three times during the raging fights near Vosges Mountains in October and November of 1944.” He is then quoted: “The last one nearly blew me apart,” he’ll give it to you without a wink.”

More description: “No one would ever suspect that Fujino has one glass eye; a tin jaw; one artificial leg; and other physical handicaps.” The Rafu Shimpo’s photo caption accompanying the photo of Truman and Fujino reads:

Truman Congratulates Fujino

Silver Star Award made in Ward Ceremony

The reference to Fujino having lost an eye in addition to his leg is one that is sometimes mentioned, sometimes not. More on that later.

Meantime, the long-defunct Shin Nichibei newspaper mentions Fujino in several articles during the 1950s and ‘60s, mostly in relation to the Nisei 100 DAV chapter — visits to the Long Beach Veterans hospital (with members of the USC sorority Sigma Phi Omega or the Girl Scouts), a DAV picnic, the results of an election of officers, etc.

Fujino even makes an appearance in the 1946 book “Boy From Nebraska” by Ralph G. Martin about famed Japanese American turret gunner Ben Kuroki, who flew on 30 bombing missions in Europe and another 24 in Japan. (See Dec. 14, 2012, Pacific Citizen)

Frank Fujino — actually Frank Fujino O’Connor — appears on page 202 of Martin’s book. The Bataan Death March is mentioned again, but here he tells Kuroki he avoided it.

As Frank opened his clothing locker to look for something, Ben saw his neatly pressed uniform with the Silver Star for killing a lot of Japs on Bataan, his first Purple Heart for wounds in the Pacific, a Purple Heart cluster for losing his leg while pushing forward to rescue the Lost Battalion of the 36th Division in France.

Fujino relays the story of visiting his foster parents in La Cañada and being refused service at ten different barbershops, including one where the barber “ . . . picked up my crutch and threw it after me and yelled, ‘We don’t want any business from Japs.’

In the last paragraph, Fujino strikes a bitter tone.

“So I fought for Democracy and I lost a leg trying to save some white Americans and now I’ll be a cripple for the rest of my life. For what, Ben? For what?”

In yet another appearance in the Pacific Citizen, Fujino is mentioned in an article by Beatrice W. Griffith (author of the 1948 book “American Me”) that appeared in the paper’s Dec. 22, 1951, Holiday Issue.

Griffith writes about the obstacles Fujino had to overcome to buy a house in Los Angeles.

One such Nisei hero, who returned from the war (after having spent three years in an Army hospital) came home with an artificial leg, a silver star, and 100 per cent disability incurred from serving with the famed 442nd Regimental Battalion. Despite his honors and injuries, when he came back he was denied the opportunity of buying a home by 15 Los Angeles real estate agents.

Finally, when Frank did find a home, he encountered another rebuff. The title officer of a title and trust company told him bluntly he “wouldn’t do business with a damn Jap.”

Griffith wrote that Fujino did ultimately prevail, but only after sitting for seven hours in the waiting room of the title company.

Fast-forwarding to the 1960s and ’70s, Fujino appears in two letters to the editor of DAV Magazine. In the May 1967 issue, a retired WAC (Women’s Army Corps) named Esther P. Hart, who was hospitalized at the Long Beach Veterans Hospital, wrote: “Mr. Fujino was instrumental in getting my compensation increased as my disability was established as one hundred percent.”

Similarly, in the August 1970 issue of DAV Magazine, William F. Celello wrote to the editor: “I can personally attest to the tremendous work being done by our National Service Officers. My thanks go especially to Frank T. Fujino of the Los Angeles Office who was instrumental in processing a claim on my behalf.”

Frank Fujino’s media appearances were not limited to the printed page. He also had a very short appearance opposite one of the most iconic and popular movie stars of all time: Humphrey Bogart.

In this publicity photo, Frank Fujino, Humphrey Bogart and Don Seki appear on the set of Columbia Pictures’ 1949 motion picture “Tokyo Joe.” Fujino has a small speaking part in the movie opposite Bogart in a nightclub scene. (Photo: Copyright © 2020 Bettman Archive. May Not Be Reprinted Without Permission.)

The movie was “Tokyo Joe,” a 1949 offering from Columbia Pictures. A publicity photo of Bogart, flanked by Fujino and fellow 442 vet (and amputee) Don Seki, appeared in several mainstream newspapers of the time. This is the same Don Seki who had no recollection of Frank Fujino.

Fujino also makes an appearance in the acknowledgements of Masayo Umezawa Duus’ 1987 book “Unlikely Liberators” as one of the many 100th Battalion/442nd RCT vets she interviewed. Nothing from that interview, however, was included in her book.

❖❖❖

Looking back over the many months that I spent compiling information about Frank Toichi Fujino, whether it was paying for copies of documents in analog form (on paper or from microfilm) or searching for the now-digital trail and ephemera of Fujino’s life, my thoughts and feelings swung from different extremes.

Initially, I only knew that Fujino was a Nisei who had served in the Army’s segregated 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team during WWII. That fact alone was significant to me.

As someone of Japanese ancestry, the meaning, the lessons, the significance, the import, the legacy and the gravitas of the service of Japanese Americans, whether in the 442nd across the Atlantic or the Military Intelligence Service across the Pacific, for subsequent generations of Japanese Americans in particular but also other Asian American groups and anyone and everyone else who is an American and calls this land home, is direct and tremendous.

Serving and sacrificing as they did, that group of men made life for everyone who followed — and not just Japanese Americans — easier, better, freer, more equitable and more respectable.

The serendipity of having bought the home once owned by this particular 442 vet and also working for the newspaper that ran articles about him, including one in particular that indeed read “like a dime thriller” makes one wonder if the definition of coincidence as being something random needs to be amended.

Last fall, when I saw the Los Angeles Examiner’s photos from the 1951 I Am an American Day and learned that Frank Fujino had lost his right leg during WWII, I was stunned. I had not known the extent of his injuries.

Upon reading that 1947 P.C. article, I was excited that such an amazing story about a 442 vet had been overlooked and forgotten. I wondered why no one had already uncovered his story? Why had no one heard of him?

Almost to a person, however, no one I had spoken to about Frank Fujino had ever heard of him or knew him. Why was that? When I spoke with Densho’s always-helpful Brian Niiya about him, he noted that because Frank Fujino died in 1983, it was a few years before younger generations began organized efforts to interview aging 442 vets and collect oral histories while they were still alive with memories intact.

The late Chester Tanaka’s book, “Go for Broke: A Pictorial History of the Japanese-American 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442d Regimental Combat Team,” was published in 1982. The late filmmaker Loni Ding’s two independent documentaries on Nisei military service — “Nisei Soldier: Standard Bearer for an Exiled People” and “The Color of Honor” — didn’t come out until 1984 and 1989, respectively.

When Fujino died, the Japanese American National Museum and the Go for Broke National Education Center were not even embryos. Perhaps that answered why few people now knew of Frank Fujino.

There is also the age factor. Were he living now, Frank Fujino would be 102. As noted, fellow 442 vets Lawson Sakai and Don Seki, who both died last summer, were 96. They presumably might have known him or known of him. But that six-year differential, plus the fact that Fujino had joined the 442 as a “replacement” in 1944, might explain why they had no recollection of him, not to mention the failing memory that can come with age.

Seki, as noted, had no recollection of Frank Fujino. This despite my sending the photo with him, Frank Fujino and Humphrey Bogart to his daughter, Tracey Matsuyama, who in turn showed it to her father. Nada.

Over the years since Frank Fujino died, there have been dozens of books and several documentaries produced about Nisei veterans, including one by me. In the bigger picture, it’s like a mini-industry, telling the stories of all things WWII — and rightfully so, since it was the pivot point in modern history that still defines why the world is as it is, three-quarters of a century after WWII ended.

Surely, even with all the nonfictional and fictional books, movies and TV shows that have been made over the intervening decades, Frank Fujino’s story deserved to be revisited and retold. That Frank Fujino could have done what was described but also have been seemingly forgotten within the Japanese American community needed to, it seemed to me, be set right.

Over time and with further investigation, however, doubts began to form. Could all of what was described in Kitasako’s article really have been true? Not knowing anything about Frank Fujino’s personality, it’s impossible to know: Was he a fabulist? Was this a case of what would now be known as stolen valor?

The Stars and Stripes newspaper defines stolen valor as “ … the phenomenon of people falsely claiming military awards or badges they did not earn, service they did not perform, Prisoner of War experiences that never happened, and other tales of military derring-do that exist only in their minds.

“Some phonies, with zero military experience, create their stories from whole cloth.

“Others, having served an honorable but peaceful stint in the military, choose to embellish their records and ‘spice up’ an otherwise unremarkable career.”

❖❖❖

There was one person who I thought might be able to clear up some of the questions I had about Frank Fujino: his daughter, the only living member of his immediate family.

I had never, however, met her. We’d never even spoken on the phone. The real estate transaction was done via her agent and mine.

After she sold the house to me, I gratefully mailed her a thank you gift, a wooden teapot I had purchased in Hakone, Japan. That was it.

Before contacting her for this story, I wanted to find out as much as I could about her father. If she was the key to learning more about him, I not only wanted to make sure I knew everything I could about him, I also needed to be careful so as not to spook her, as this seemed like a potentially sensitive subject. Why should she trust me or my motives? She didn’t know me, other than as the person who bought her parents’ house.

It was more difficult than I thought it would be. Although I had her phone number and address, when I called, she would hang up on me. My voice messages, text messages and letters went unanswered.

Finally, she called me after I mailed her yet another letter. I got the feeling she just wanted me to stop bothering her. She agreed to meet with me one time, just to get it over with.

So, we met one afternoon last summer after her workday ended. With the Covid-19 safety protocols in mind, we sat down to chat at an outdoor restaurant not far from her place of work, masks in place.

Although she answered my questions without hesitation, her answers were, at first, very short. Still, they provided some insight. For instance, she grew up not in Culver City, like I had presumed, but in L.A.’s Mar Vista area. The house she grew up in was on Gilmore Avenue.

My research later found that Frank and Yuriko Fujino bought the Culver City house in May of 1975, the year she graduated from high school. She didn’t spend much time in the Culver City house.

As for how her parents met, she only knew that it was after the war. She said her mother, Yuriko Taketa, had been incarcerated at the Gila River camp in Arizona during WWII and worked there as a nutritionist.

It turned out that she had a fraught relationship with her father. While she allowed that when she was young, she was “his buttercup,” their relationship became strained during adolescence.

Although she was very close to her mother, who died on Feb. 12, 2013, she said her father was “harder to get along with.”

“When I was growing up, I was the rebel child. I was the rebel, OK?” she said. “My dad kicked me out when I was 18.”

The reason: her boyfriend. He was older than she and Chinese. “They were very prejudiced,” she said. “He was a good fellow. Kind of like a Jesus fanatic, but other than that, he was a nice person.”

Before she was “kicked out” of the house, she recalled getting into a car accident at 17-1/2 when she was learning to drive with a learner’s permit, with her father in the car.

“I smashed up my mom’s car. He’s the one who told me to go through the light, and I ran into a cement truck,” she laughed. “I can laugh now because it was so long ago, but I never really drove after because my dad blamed it all on me.

“There was a rough side to my father,” she continued. Her late brother, Arnold, she said, was “always afraid of my dad.”

She also, however, has some fond memories of her dad from her younger years, including shooting hoops and him, with just one leg, teaching her to ride a bike. “It was really difficult,” she said.

She remembered how he had more than one prosthetic leg, all of them very heavy and made of wood. She remembered that his last wooden leg had a hydraulic knee, which helped him walk better.

In his later years, though, Frank Fujino used a wheelchair to get around.

As for reports of her father having a lost an eye, she said this was not true.

Before her dad died, she heard from Arnold that their father, who was hospitalized and on his death bed, wanted to see her.

“When I had last seen him, he weighed over 200 pounds,” she said. “When I saw him, when I tried to reconcile with him, he was down to 120.” According to Frank Fujino’s death certificate, the cause of death was septic shock as a consequence of stage IV lymphoma.

Despite getting a better idea from his daughter of who Frank Fujino was, there were so many questions still remaining. But since she was just somewhat uncooperative, I had to boil them down to what I thought were most essential.

I reached out over the phone. Again, when I called, I was hung up on. Finally, I texted first, then called. She answered, and I received answers to the two short questions I had. One, did she know whether her father had been adopted? Two, did she know whether he had ever been stationed in the Philippines?

To both questions, she said no.

I had many more questions, of course. But I’ve come to the conclusion that finding some answers 38 years after his death may be impossible.

❖❖❖

Finding Frank Fujino did not go in the direction I had initially thought it might when I learned of John Kitasako’s Pacific Citizen story. That 1947 article contained elements that were true. Frank Fujino had served in the 442nd. He had lost a limb as a result of injuries sustained in combat.

But some of the rest of what is in that article? Well, let’s just be charitable and say some things don’t add up.

Terumi ‘Terry’ Kato of Hawaii and Frank Fujino of California, both 442 vets and amputees, became friends while recuperating at the Walter Reed Army Hospital. (Photo: Courtesy of the Nisei Veterans Committee, Seattle, Wash.)

If Frank Toichi Fujino embellished and fabricated some of his experiences, determining today his reasons for doing that would be purely speculative. If he did make up some stuff, his reasons for doing so are lost to history. To me, his having lost a leg meant that he certainly didn’t need to gild the lily of his experiences.

But if he was a fabulist, I still cannot judge him too harshly — and to anyone who would do so, I’d have to say first walk a mile with his crutches. The trauma of losing a leg and then the traumas of undergoing several operations, not to mention overcoming the obstacles of rehabilitation and making peace with living the rest of his life with such a major handicap could scramble anyone’s thoughts.

In spite of the circumstances Frank Fujino found himself in, he dedicated the rest of his life to helping his fellow wounded veterans as a national service officer for the Disabled American Veterans. That’s not nothing.

Good or ill, true or false, it can safely be said that Frank Toichi Fujino is forgotten no more.

❖❖❖

In the Sept. 1, 1980, edition of the Los Angeles Times, Charles Hillinger wrote about the first reunion between the men of 2nd Battalion, 141st Infantry of the 36th Division, aka the Lost Battalion, and the men of 442nd Regimental Combat Team. It took place in Dallas, Texas.

The article quoted Jack L. Scott, president of the 36th Division Assn., who said, “You are our heroes. To be with you men again is the most powerful experience I have ever had.”

Sen. Daniel Inouye of Hawaii was the event’s principal speaker. Several other Nisei are quoted in the article. Shim Hiraoka of Fresno, Calif. Hoppy Kaneshina of Gardena. Calif. Monte Fujita of Los Angeles. Hideo Takahashi of Ontario, Ore. Shiro (Kash) Kashino of Seattle. Victor Izui of Evanston, Ill. James Okimoto of Kaneohe, Hawaii. Henry Nakada of Homer, Alaska.

There was one other man quoted.

“I paid a high price — my leg — to get the Texans out from behind the enemy lines,” said Frank Fujino, 62, of Culver City, Calif., who came to the reunion in a wheelchair. “I have no regrets,” he added.

The marker for Frank Toichi Fujino. He is buried next to his wife, Yuriko Fujino, at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Los Angeles. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Funding to research this article came from a George and Sakaye Aratani CARE Award, which is sponsored by the UCLA Asian American Studies Center. The author would like to thank the following entities and individuals for their help with this article: the Los Angeles Public Library, the University of Hawaii Library, the USC Digital Library, the UCLA Library, the Japanese American National Museum, the National Personnel Records Center, Getty Images, Google, Kanji Sahara, Seiki Oshiro, Brian Niiya, Peter Duus, Lane Hirabayashi, Satsuki Ina, Rev. George Matsubayashi, Mary Uyematsu Kao, John Kao, Eric Saul, Frank Toichi Fujino and his daughter.

* After publication, microfilm of the Nov. 18, 1946, Los Angeles Daily News showed that Matt Weinstock’s column was used verbatim in the March 6, 1947, Hawaii Star.

Read related item here.