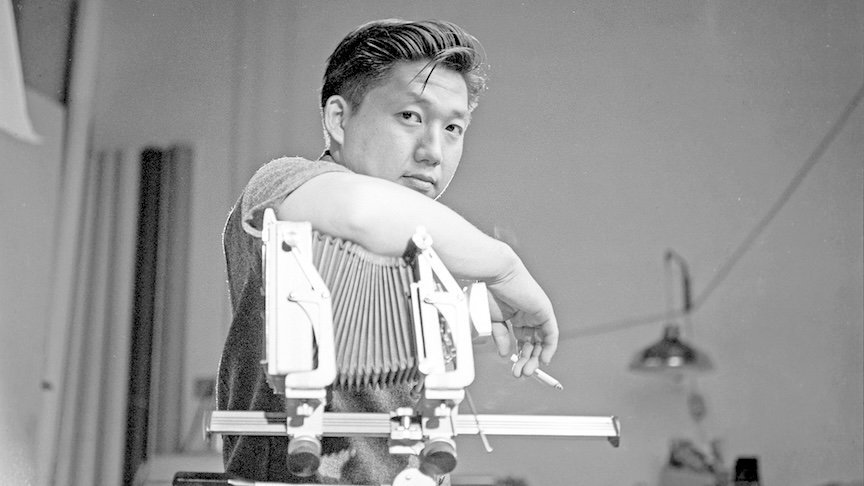

Although Bob Nakamura became known for his motion pictures, earlier in his life, he had found employment as a still photographer and photojournalist. (Photo: Robert A. Nakamura (Courtesy of “Third Act” Copyright Robert A. Nakamura)

Creative force played key roles at VC, UCLA, JANM’s Media Center.

By P.C. Staff

Robert Akira Nakamura, known to his legion of friends, colleagues and students as Bob, the filmmaker whose works spanned decades and experimental, documentary and dramatic genres and who helped to found and lead several still-extant community organizations with missions dedicated to visual storytelling, died June 10 at home in Culver City, Calif. He was 88.

Apropos of his life in pictures, Nakamura’s struggles with Parkinson’s disease in the waning months of his life were starkly and unflinchingly captured in the award-winning documentary “Third Act,” released earlier this year (see April 4, 2025, Pacific Citizen, tinyurl.com/2khbzd6s).

Like many of his generation of Japanese Americans who resided along the West Coast when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, which resulted in America’s entry into World War II — and the forced removal from the West Coast states and subsequent incarceration of more than 125,000 ethnic Japanese — Nakamura was deeply affected by his nation’s betrayals of its ideals of due process, equal treatment under the law and perquisites of citizenship.

Unlike most of his peers, however, Nakamura found an outlet to deal with the defining trauma he experienced as a child: filmmaking. Decades into adulthood, that resulted in his trippy, seminal experimental 1971 documentary “Manzanar,” named for the War Relocation Authority Center where he spent part of his childhood after being born in the Venice area of Los Angeles. In 2022, “Manzanar” was added to the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry.

Nakamura’s filmography also includes “Wataridori: Birds of Passage,” the drama “Hito Hata: Raise the Banner” (co-directed with Duane Kubo), “Fool’s Dance,” “Moving Memories,” “Looking Like the Enemy” and “Toyo Miyatake: Infinite Shades of Gray,” about the photographer who was also incarcerated at Manzanar and had famously smuggled in lenses and other camera parts to build a working camera to document life in camp from an inmate’s perspective. (“Manzanar,” “Wataridori” and “Hito Hata” can be viewed at tinyurl.com/4jd58xcz. “Looking Like the Enemy” can be viewed at tinyurl.com/5d4yvpa7.)

When he was still a teenager in the 1950s, Nakamura found work as a freelance photojournalist for the Los Angeles Examiner and the International News Service. He went on to graduate from Art Center College of Design in 1966 and build a career as a successful commercial photographer — seemingly achieving the American Dream.

The ferment of the era — the Civil Rights and Anti-War movements — and the unresolved psychic scars from Manzanar, however, pulled Nakamura in another direction. With Kubo, Eddie Wong and Alan Ohashi, he helped co-found the community-based nonprofit Asian American media organization Visual Communications, where Nakamura served as its founding director.

In 1975, Nakamura’s pull toward academia began when he earned an MFA from the University of California Los Angeles’ School of Theater, Film and Television. The association with UCLA would loom large in his future. As a grad student, he was part of the film school’s Ethno-Communications Program. After becoming a film professor in 1987 at the UCLA TFT and an Asian American Studies professor in 1994, he would in 1996 revive the name as a teaching program.

According to UCLA, Nakamura nurtured future Asian American film talent that included such names as Akira Boch, Eurie Chung, John Esaki, Evan Leong, Justin Lin and Ali Wong.

The Japanese American National Museum was yet another community institution where Nakamura made an impact. He was among those in JANM’s original advisory committee in 1985 and would later become the founder of its Frank H. Watase Media Arts Center, as well as the JANM Moving Image and Photographic Archive.

With Karen Ishizuka, his producing partner and wife of 46 years, JANM awarded Nakamura its inaugural JANM Legacy Award in 2016 for their “their multiple contributions in filmmaking, advocating for the cultural and historical significance of home movies, documentation of community events and recording of oral histories.”

“His legacy will endure in every story we tell,” said JANM President and CEO Ann Burroughs.

Nakamura is survived by his wife, Karen L. Ishizuka; daughter, Thai Binh Etsuko Checel; and son, Tadashi Nakamura; brother, Norman Nakamura; daughters-in-law, Heather Wielgos and Cindy Sangalang Nakamura; and several grandchildren.

Plans for a public memorial are forthcoming.