These artist’s renditions the Fourth & Central project show how the proposed 44-story tower on the far left was reduced on the righthand side to 30 stories. Meantime, the image on the right shows that the proposed height of the white tower has been increased. (Photo: Continuum Partners LLC)

Gentrification? Redevelopment? Urban renewal?

Pressures facing America’s ethnic enclaves are nothing new.

By George Toshio Johnston, P.C. Senior Editor

(Editor’s Note: Following is the second part of an article about how recent national trends in redevelopment and gentrification are impacting L.A.’s Little Tokyo, the nation’s largest historic “Japantown.” Part One was published in the Sept. 20, 2024, issue of the Pacific Citizen.)

When Charles Dickens wrote his 1859 novel “A Tale of Two Cities” and its famous, oft-quoted opening — “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness …” — he was definitely not writing about Little Tokyo.

First, Dickens was about 25 years too early, since the agreed-upon “birth year” of the area of Los Angeles known as Little Tokyo was 1884, and second, the titular two cities were London and Paris.

In 2024, however, when it marked its 140th year, Little Tokyo seems to be, depending on your perspective and political bent, two very different places in the same space.

In one version of Little Tokyo, legacy Japanese Americans and Japanese American businesses are being displaced and driven out by greedy property owners who could not care less about the area’s roots and cultural legacy, such that on May 1 the nonprofit National Trust for Historic Preservation put it on its annual list of “11 Most Endangered Historic Places.”

Why the dire designation? “Little Tokyo is one of only four remaining Japantowns in the United States and one of the oldest neighborhoods in Los Angeles, but its unique character is endangered by large-scale development and transit projects and displacement of legacy businesses and restaurants.”

The Fourth & Central project was the main topic at the Oct. 2 meeting of the Little Tokyo Community Council. A representative from Denver-based Continuum Partners LLC had been scheduled to attend the meeting but did not. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

In the other version of Little Tokyo, it is busier and more successful than it has ever been in its seven score of existence, according to its boosters. In that version, Little Tokyo attracts 10 million visitors annually — a 10 percent increase over last year — as a destination for domestic cosplayers who might not be able to afford a trip to “Big Tokyo” but can certainly visit the next best thing to buy the latest manga and pop culture artifacts from Japan, as well as the international tourists drawn in by the so-called Shohei Ohtani effect, named after the Los Angeles Dodgers’ superstar whose likeness took over a wall of the Miyako Hotel on First Street in the spring.

Then there are, of course, Southern California’s Japanese Americans who, despite being dispersed from Santa Barbara and Oxnard to Los Angeles and Orange counties and San Diego, still see Little Tokyo as their cultural and spiritual hometown.

So, in this tale of two Little Tokyos, which version reflects objective reality? Is it strictly one or the other? Or, can both be true — or maybe trueish — at the same time?

◊◊◊

Speaking in front of the entrance to the Japanese American National Museum at the May 1 news conference where it was announced that Little Tokyo had been named one of the year’s “11 Most Endangered Historic Places” were Linda Dishman, former CEO of the Los Angeles Conservancy, on hand to represent the National Trust for Historic Preservation; Kristen Hayashi, director of collections management and access and a curator at JANM; Kristin Fukushima, managing director of the Little Tokyo Community Council; Bishop Noriaki Ito, Higashi Honganji Buddhist Temple; Hirokazu Kosaka, the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center’s master artist in residence; Carol Tanita, Rafu Bussan co-owner; and Bill Watanabe, founding executive director of the Little Tokyo Service Center, a founder of Little Tokyo Historical Society and Asian Pacific Islanders in Historic Preservation.

(From left) Carol Tanita, Bill Watanabe, Gilda Hernandez and Hirokazu Kosaka listen to Kristin Fukushima on Feb. 1. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

As to why Little Tokyo received its new designation, Dishman said, “The National Trust listed Little Tokyo on the endangered list this year because its unique character is under threat.”

The nature of that threat was alluded to by the event’s other speakers. “I want to thank the National Trust for Historic Preservation for giving Little Tokyo this recognition and designation to help us in that fight to preserve this neighborhood against many threats and obstacles that might be coming our way in terms of gentrification and economic changes,” said Watanabe, who also pointed out the Little Tokyo subway station across the street from where he was speaking that had opened in 2023. “It’s a good thing that’s bringing people to Little Tokyo. But at the same time, it’s changing land values and rents here, so small businesses may have difficulty to stay in business from this point on.”

Not coincidentally, four of the speakers that day were representing groups from Sustainable Little Tokyo, a four-organization coalition comprised of the JACCC, LTCC, LTSC and JANM.

According to Fukushima, Sustainable Little Tokyo was formed to find ways to maintain for future generations the Little Tokyo neighborhood, considering its cultural and historical background, arts and culture, as well as its economic and environmental sustainability. For her, its formation more than a decade ago was part of a “new strategy to approach gentrification and displacement.”

◊◊◊

Rafu Bussan store manager Carol Tanita speaks at the Feb. 1 news conference in Little Tokyo. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Historically, Little Tokyo is no stranger to displacement. After the United States declared war on Japan on Dec. 8, 1941, it was just a matter of months before ethnic Japanese people, U.S. citizens or not, were removed from the coasts of California, Oregon and Washington. Even JACL and this publication, Pacific Citizen, had to hightail it to Utah’s Salt Lake City, which had an extant Japantown of its own, during the years of World War II.

During that time, Little Tokyo became a new home for African Americans who moved from the South to take advantage of employment opportunities in California’s war-fueled manufacturing boom. The area became known as Bronzeville — until Japanese Americans returned from the 10 War Relocation Authority Centers to the West Coast in general and Little Tokyo in particular to reclaim the area and return its name to Little Tokyo. Then, in the late 1940s, under the City of Los Angeles’ right of eminent domain, a section of (now historic) Little Tokyo was seized as the site of Parker Center, the headquarters of the Los Angeles Police Department, and an adjacent parking lot.

In the 1970s, the new buzzwords were “urban renewal” and “redevelopment” — and once again, the environs of Little Tokyo were in the crosshairs. Speaking in 2023 at the JACL National Convention’s plenary titled “State of Ethnic Enclaves,” Fukushima gave background on this era. “In the’70s and ’80s, which was both the redevelopment period for Little Tokyo, as well as, of course, the Asian American movement, a lot of folks were finding their identity, saying, ‘What’s going on back in our home communities?’” she said.

“As young folks came to Little Tokyo, they realized that a lot of things were changing. A lot of small businesses were being displaced. The SRO hotels were being torn down. Small businesses were under threat. Residents were under threat. So, groups like the Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization were created. They were an anti-eviction, anti-displacement group. I always make sure I include this history because I really think Little Tokyo would not be here today if it weren’t for their efforts to really actively fight for this neighborhood and also create organizations like the Little Tokyo Service Center, the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center. A lot of the organizations that serve Little Tokyo and the Japanese American community today were created back then.”

After the turn of the century, with construction of a new LAPD HQ a few blocks away at First and Main in 2009, Parker Center’s days were numbered, and it was demolished in 2019 — and that created a rare opportunity whereby a seized area that was once part of an ethnic enclave could be returned to that community and be redeveloped in a way that modernly reintegrates it with its historic roots.

Therefore, on Feb. 13, ground was broken for construction of the ambitious First Street North project, a reclamation of an area once part of Little Tokyo that will become the new home of the Go For Broke National Education Center and also a place for affordable housing, community-based businesses and office space for nonprofits (see April 26, 2024, Pacific Citizen).

◊◊◊

The machinations and changes occurring in Little Tokyo are not isolated. Historic Asian American ethnic enclaves such as San Francisco’s Japantown, Seattle’s Chinatown-International District, Denver’s Sakura Square, Salt Lake City’s historic Japantown and Philadelphia’s Chinatown are all grappling with different — but similar — scenarios that fall under today’s catch-all description, gentrification — even when the definition of “gentrification” varies depending upon whom you ask.

As was pointed out at the 2023 plenary, when the status quo facing Philadelphia’s Chinatown — namely a bid by the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers to build a new arena to its south — this latest challenge is nothing new.

Dr. Mary Yee speaks at the “State of Ethnic Enclaves” plenary on July 22, 2023, in the main hall of JANM during the JACL’s National Convention.

“In Philadelphia, we have been saving Chinatown for over 50 years from a range of projects … an interstate, downtown mall, casinos, convention center and so on,” said Dr. Mary Yee, who has been active in the fight to protect Philly’s Chinatown and also founded Asian Americans United and the Yellow Seeds newspaper.

“The 76ers are thinking of building a stadium for 18,000 people,” said Yee. “We think that it’s disingenuous for them to say that their arena will not harm Chinatown. They’re saying, ‘We’re not going to take any land from Chinatown, so why are you upset?’ But it’s clear to us that there are really serious economic and traffic implications for this project. So, we’re thinking, ‘How will it be if there are 18,000 people entering or visiting this arena during dinner hours for Chinatown restaurants and businesses?’ And you can imagine that this is going to create public security issues, along with impacts on small businesses that will be competing with the concessions in the arena.”

Incidentally, in 2023, Philadelphia’s Chinatown was added to that year’s list of “11 Most Endangered Historic Places.”

If viewed from a summit with sightlines that cross cities and states, it’s safe to conclude, then, that the challenges facing Little Tokyo are A, nothing new; and B, not unlike the pressures that other historic Asian American ethnic enclaves face today.

What might be new, however, at least when compared to, say, the 1940s, is the willingness of stakeholders to use the political and legal systems, take stands and, to use a term of art from the not-so-distant past, fight the power.

Part of that ethos means participating in the process needed to approve and move forward on redevelopment projects. One example was the discombobulated, snafu-plagued public environmental impact hearing held by the City of Los Angeles’ City Planning Commission via Zoom on Nov. 20 to address the Fourth & Central project.

One speaker, Mia Barnett of Nikkei Progressives, said, “First of all, the city should really be ashamed that you didn’t prepare for this hearing properly and wasted so much time on technical issues. People work during the day, and not everyone can take hours off of work to watch you all struggle to figure out how Zoom works. Secondly, Continuum Partners has failed to present the community with the changes to their project. They were supposed to on Oct. 2, but they canceled, and they never rescheduled.”

Little Tokyo Business Association President David Ikegami (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Not everyone, however, including some Japanese Americans with ties to Little Tokyo, opposes the Fourth & Central development. Many of the meeting’s participants expressed support. One of the supporters was David Ikegami, president of the Little Tokyo Business Assn. and president of DTI Corp.

No newcomer to Little Tokyo, back in the mid- to late-1980s, Ikegami was involved with the development of Little Tokyo Square at Third and Alameda streets, which is now Little Tokyo Market Place.

Ikegami points out that Fourth & Central is not located in Little Tokyo, but rather in the adjacent downtown industrial district and that the current business on that property, Los Angeles Cold Storage Co., has been around since 1895 and owned by the Rauch family for more than a century.

While he says he understands and appreciates the concerns of Little Tokyo Against Gentrification, Ikegami has a different take on the situation. “Converting what is an existing cold storage warehouse facility into a multistory, multibuilding, $2 billion development, which is absolutely beautiful, is not gentrification,” Ikegami told the Pacific Citizen. “Gentrification is when you displace residents or businesses and … there is no displacement going on.”

Regarding accusations that the developer, Continuum Partners LLC, has been uncooperative with different Little Tokyo-based stakeholder groups, Ikegami disagrees. “I think that they’ve bent over backwards listening to all the different constituencies, LTBA included, and really have tried to work concessions and have done so.

“They’ve lowered the height of one of the main buildings, the one closest to Little Tokyo, by 10 or 15 stories — I can’t remember exactly — and they’re going to add that square footage further south on the block, but it’s going to be a much lower skyline when you look at it initially from Little Tokyo,” Ikegami continued. “They’re creating reduced rents for legacy businesses, so that businesses that wish to move into their property have much reduced risk.”

◊◊◊

The saying that “the only constant is change” applies also to what is happening in Little Tokyo. Back in August, LTAG wanted to present a revisit/redo demand regarding the environmental impact report needed to proceed on Fourth & Central to L.A. City Councilman Kevin de Leon. Now that itself needs to be revisited since he lost his seat to challenger Ysabel Jurado after the Nov. 5 election.

Then, there’s the possibility that the Supreme Court’s decision on Seven County Infrastructure Coalition v. Eagle County, Colorado may limit how much environmental impact reports can have on the ability to delay or stop construction projects.

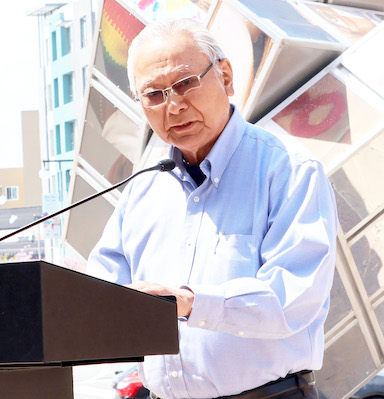

Bill Watanabe, who is now a member of the Little Tokyo Community Impact Fund, speaks at the Feb. 1 news conference in Little Tokyo. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Despite the “only constant is change” saying (and the possibility of eminent domain), one constant that still matters is ownership. With ownership comes self-determination because when you own the land upon which your business sits, you can’t be evicted at the whim of, say, a new landlord.

Ownership, it turns out, is a word that both Ikegami and Watanabe can agree upon.

“The businesses that have been able to be successful in the community, some of them have purchased their own properties, which is really amazing,” said Ikegami. “It’s insurance that their rents won’t go up.”

Watanabe, meantime, belongs to Little Tokyo Community Impact Fund. A visit to its website (littletokyocif.com) reveals why it was created: “We established the Little Tokyo Community Impact Fund (LTCIF) to directly address these challenges and try to preserve the legacy of Japanese American family owned businesses, cultural institutions and spiritual centers in Little Tokyo.” LTCIF is, in his words, a California incorporated investment fund.

“If you don’t own it, you can’t control it. And so ownership becomes the key thing to try it and control what these properties will be,” Watanabe told the Pacific Citizen. “So yeah, we want to control it. We want to own it so that we can help direct the future of those properties.”

If there is a place where the tale of the two Little Tokyos can meet and find common ground, literally, ownership may be the key by which all parties live happily ever after.