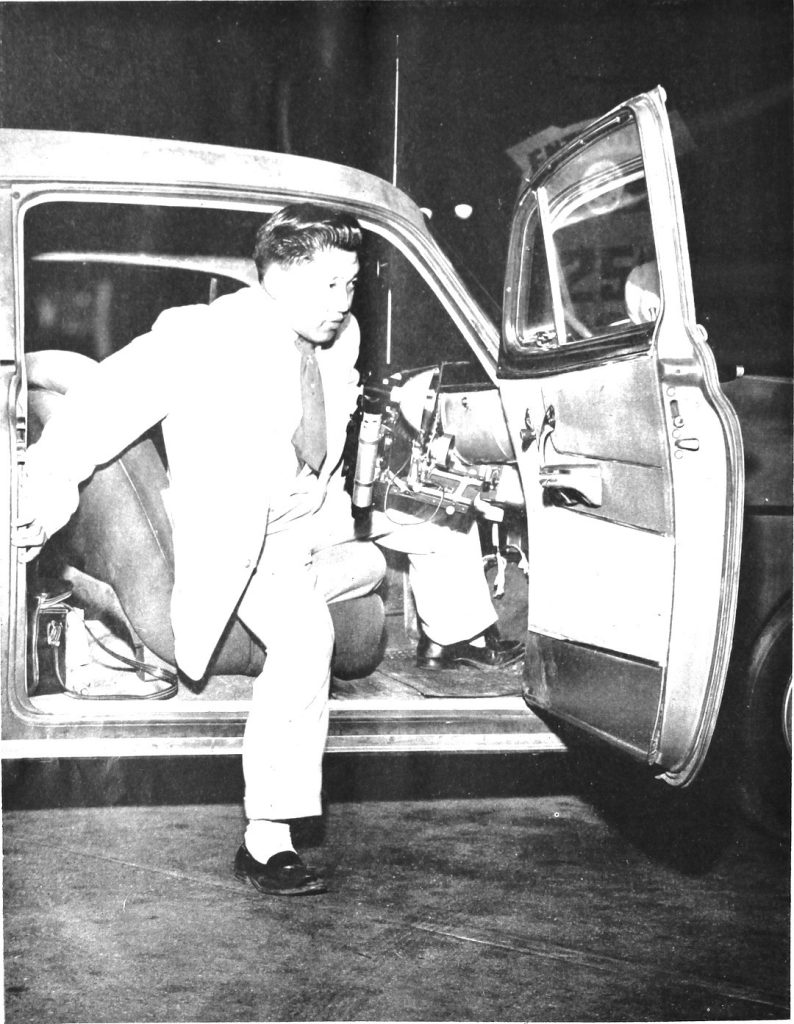

Young Bob Nakamura (Photo: Robert A. Nakamura. Courtesy of “Third Act,” Copyright © Robert A. Nakamura)

Second-gen filmmaker Tad Nakamura completes paean to Robert Nakamura.

By Alex Luu, P.C. Contributor

Tadashi Nakamura (Photo: Tibrina Hobson/Getty Images)

Director Tadashi Nakamura begins his documentary “Third Act” with a phrase that will become a refrain throughout the film’s 90-minute running time. The phrase is simple yet full of conviction: “My whole life, I always knew I had to make a film about my dad.” The phrase is spoken by Tad himself, about his father, Robert A. Nakamura.

It’s a wonder why prior to “Third Act,” no one had ever made a movie about the elder Nakamura. Lovingly known to longtime colleagues and family/friends as “Bob,” he has lived many lifetimes in his 88 years as a filmmaker, producer, photographer, activist and a founder of no less than three seminal media arts organizations: Visual Communications (1970), UCLA Center for Ethno Communications (1996) and Japanese American National Museum’s Frank H. Watase Media Art Center (1997), respectively, where Tad Nakamura now serves as its director.

Bob Nakamura documented the first pilgrimage to Manzanar in 1969; directed the searing film “Manzanar” (1972); spent a collective 33 years as assistant, associate and full professor at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film and Television and Asian American Studies Department (1978-2004); and was associate director of the UCLA Asian American Studies Center (1993-2011). He also co-directed the 1980 landmark film “Hito Hata: Raise the Banner,” about the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, and produced 28 films on the Japanese American experience.

Yet, with all of his countless accomplishments and accolades, it’s also a wonder why Bob Nakamura is not a better-known documentarian, like Ken Burns or Michael Moore. In the opening minutes of “Third Act,” Tad Nakamura narrates, “My father is known as the godfather of Asian American cinema, but ironically, most people outside of our community have never heard of him. I don’t want him or his work to be forgotten.”

Years before becoming a filmmaker, the long-defunct Scene magazine — archived at Densho.org — profiled Robert Nakamura in its September 1954 issue when he was an 18-year-old freelance photojournalist and copy boy at the long-defunct Los Angeles Examiner and the long-defunct International News Service.

Bob Nakamura’s relative obscurity in the mainstream serves as part of his son’s motivation to make the film. “Maybe an earlier generation knows who my dad is, but a lot of people my age and younger don’t,” Tad Nakamura said, “or they don’t even know a lot about the history of VC (Visual Communications) or early Asian American cinema. A lot of people think it started with ‘Crazy Rich Asians.’ It was early on where I became protective of his legacy.”

Most documentarians have an objective distance and relationship to their subject matter. “Third Act” is that rare exception where a son is telling his own father’s story. As to whether this process would be too close or too partial, Tad Nakamura actually makes a strong case for flipping the rules of a traditional documentary. “It would be a given that if there was gonna be a film made on my dad, I would make it,” he said. “I wanted to do it because I felt I could trust myself. I wouldn’t trust anyone else to do my dad justice.”

In addition to having an irrefutable connection with his subject matter, Tad Nakamura brings to “Third Act” an impressive 20 years of experience as an Emmy Award-winning filmmaker. He was named CNN’s “Young People Who Rock” for being the youngest filmmaker at the 2008 Sundance Film Festival, and his previous films include “Pilgrimage” (2006), “A Song for Ourselves” (2009), “Jake Shimabukuro: Life on Four Strings” (2013) and 2024’s “Nobuko Miyamoto: A Song in Movement.”

And so, “Third Act” wastes no time in presenting Bob Nakamura’s influential role in Asian American media for the past eight decades. The film features an assortment of black-and-white/color photographs and 16mm footage that functions as a visual timeline of Nakamura’s prolific oeuvre, dating all the way back to the late ’60s.

The photos range from a shot of Bob Nakamura proudly posing next to his still camera to him manning a bulky Arriflex movie camera to him directing “Hito Hata” perched atop a crane. There’s even an iconic photo of him with a cigarette, grinning and looking very much like an Asian American version of Hunter S. Thompson — and in Tad Nakamura’s proud assessment — “a f*****g badass.”

The celebratory and downright flexing of the pioneering filmmaker in his heyday is coupled with brief day-in-the-life scenes of present-day Bob Nakamura. There is also a glimpse into the elder Nakamura’s humor and playfulness.

When Tad Nakamura asks why he wants to make “Third Act,” his father deadpans, “To further your career” and laughs. Bob Nakamura also can’t help but joke, “So you’ll be guiding it though, right? Because you’re the director, and I just interfere because I’m a filmmaker!” This tender and humorous interplay between father and son quickly reveals their close familial bond.

Another seemingly innocuous scene that accentuates their deep bond is when they make their annual trek to UCLA football games. Having graduated from UCLA with an MFA in 1975, Bob Nakamura introduced his son to the games when he was just a young boy. This continued on throughout Tad Nakamura’s own later years as a Bruin in the early 2000s and has remained as a tradition since.

This sacred tradition is shockingly broadsided in one of the film’s most harrowing scenes. At a UCLA football game, Bob Nakamura becomes disoriented and agitated. He walks and walks and walks, seemingly going nowhere as he tries to figure out what exactly is happening to him. A vast contrast from earlier scenes, the elder Nakamura’s demeanor and voice are disparate as he barely finds the words to match his confused mental state. “Walking to the Rose Bowl, I felt totally out of control, and that’s what really kinda scared me,” he shared. Back in the car after the game, Bob Nakamura struggles to process what happened. “Well, I feel I got all kinds of symptoms right now. . . . I can’t breathe, I can’t hear. My voice is going. My legs are getting really tired,” he explained.

After checking into UCLA Medical Center and seeing a neurologist, it is confirmed that Bob Nakamura has Parkinson’s disease. With this shocking diagnosis, the filming of “Third Act” took on an even more urgent pace.

This unexpected turn of events more than challenged Tad Nakamura as a filmmaker. Instead of sticking to the original idea of a biopic, he took a risky chance by restructuring the overall focus of the film. “Once he got diagnosed, it kind of evolved into the film that it is,” Tad Nakamura said.

What follows is a bold roundabout in the direction, structure and tone of “Third Act.” Gone are the more carefree scenes that marked the beginning of the movie. Bob Nakamura gets more candid and somber in his interviews, baring his soul and peeling the layer off of his own bravado to reveal a very broken man who has been struggling with depression for many years.

Ironically, the combination of decades-long depression coupled with Parkinson’s emboldened Bob Nakamura to be open in expressing his inner thoughts and emotions. Tad Nakamura also attests to his father’s willingness to be more transparent.

In a powerful scene, Bob Nakamura reflected, “I’m in a really good place in terms of family, finances, creative work, friends, community. But, regardless of that, every morning you wake up feeling miserable; there’s a feeling in the pit of your stomach, and you don’t want to get out of bed.”

Bob Nakamura pinpoints that pit-of-the-stomach feeling by saying, matter-of-factly, “Everything comes back to camp, and everything comes back to Manzanar.”

It turns out that Manzanar has had a vice-like grip on Bob Nakamura’s heart, soul and psyche ever since he was a boy. At just 6 years old, he and his family were incarcerated there until the end of WWII. In a pivotal moment from “Third Act,” he takes a painful deep dive into the recesses of the past and remembers how Manzanar had impacted his own father, Harukichi George Nakamura. In a weary tone, Bob Nakamura recounted, “Before WWII, before camp, Jichan had kind of worked his way up from a gardener to a businessman. He owned a house, and we had a piano in the living room. They were kind of joining the middle-class as much as a person of color can.”

In a deft touch, Tad Nakamura gives a visual companion to his father’s testimonial by including footage from Nakamura’s own 1971 film “Manzanar” — Nakamura as a young boy smiling happily, Jichan watering his plants, the whole Nakamura family posing in front of the family business’ storefront sign in 1935 — accentuating the fact that once upon a time, the Nakamura clan did live a kind of all-American life before incarceration. This film within a film technique is twofold in that it solidifies Bob Nakamura’s narration and reminds the viewer of one of America’s most disgusting transgressions against its own citizens.

The idyllic shots of the happy Nakamura family segue to grim footage of racist signs denouncing the existence of the Japanese at the onset of WWII. Nakamura continued, “But then that was all wiped out. . . . After Pearl Harbor, overnight, I was a Jap, I had the face of the enemy. Jichan was under a lot of pressure because he was very high up in judo. Most of the judo instructors, like other community leaders, were taken away and put into maximum security prisons. For whatever reason, they missed my dad. But he was so scared of being taken away that he took everything that was related to Japan — pictures, letters, anything with Japanese writing, he buried in the backyard or burned.”

Unfortunately, like most Japanese American families who had to start all over postcamp, Jichan, having lost his family business, went back to being a gardener. “Coming back to postwar Los Angeles, it was outright unabashed racism.”

Tadashi Nakamura, Bob Nakamura and Prince Nakamura in a scene from “Third Act,” directed by Tadashi Nakamura

Photo: Lou Nakasako, Courtesy of THIRD ACT/ COPYRIGHT ©Tadashi Nakamura

The trifecta of Jichan’s own erasing of the Nakamura family’s Japanese ancestry, incarceration in Manzanar and having to start postwar life from scratch served as a kind of “perfect storm” that created a lifelong schism between him and Bob Nakamura, as well as sowed the seeds of generational trauma and emasculation that would haunt both men.

This gritty reconciliation of how he felt about his father and his own battles with racism leads to the most gut-wrenching scene from “Third Act” wherein Bob Nakamura, with the unbearable weight of depression and Parkinson’s, completely releases all the decades’ worth of guilt, shame and trauma that has been repressed for way too long. What transpires next is at once tragic and excruciating to watch as it almost teeters on the edge of voyeurism, which once again begs the question: Is Tad too close to his subject matter?

“So, that particular scene — it wasn’t planned at all. I think it was the day after Thanksgiving, and . . . he started talking and talking, and I just took out my phone and started filming,” Tad Nakamura remembered. “He’s always talked about how racism and camp will destroy you. It f**ks up the way you see yourself and the world. . . . He had expressed that to me in a more conceptual, intellectual, theoretical way. But at that moment, it was the emotion of that.

“That’s the first time I’ve ever seen my dad that vulnerable,” he said. “It was the first time where, you know, I did emotionally have to just put down the camera. I probably start off as Tad, the filmmaker, filming the content, but then by the end, I just have to be the son and give my dad a hug.”

Just as Bob Nakamura is finally coming to a harsh reckoning of his own life and reassessing his troubled relationship with his own father, Tad Nakamura is also starting to relook at Bob Nakamura through a more enlightened perspective.

“I never knew my dad felt this way about himself or my Jichan. I always thought of him as this proud Asian American filmmaker,” he offerered, “so I guess it was just hard to learn that he was so ashamed of who he was, and it hurts even more to know that he had no one to talk to, no one to help him understand what was going on or how to cope.”

Bob Nakamura’s mantra of “Everything comes back to camp, and everything comes back to Manzanar” is doubly layered in that the place and source of trauma can also provide a sort of release from said trauma. And so the latter half of “Third Act” provides an opportunity to both exorcise the searing pain held internally for decades and reclaim a sense of dignity.

Tad Nakamura includes footage from his own film titled “Research Trip for Pilgrimage” (2004) in which his father takes him to Manzanar for the first time. Once again, employing the film-within-a-film motif, the son is introduced by the father to the historical place that maligned thousands of Japanese Americans’ lives.

Some 20 years later after Tad’s first visit to Manzanar in 2004, everything has come full circle yet again. In the coda of “Third Act,” Tad Nakamura is taking his own son, Prince, there at the behest of Bob Nakamura. When asked why, the elder Nakamura said, “I guess it is getting back to homecoming. . . . On one hand, I want to show him where his grandfather was in, essentially a prison. But at the same time, I like to show him where I used to get the branches to make the slingshots with. There’s some really negative stuff (about Manzanar), but I can’t help myself. There are positive things that I wouldn’t mind showing him.”

Representing the three ages of man, seeing three Nakamura males walking around and exploring the grounds of Manzanar is tender and bittersweet. Holding Prince’s small hand, Bob Nakamura shows him the lay of the land and points out lizard and snake holes that he used to come across as a boy in camp. Grandfather to grandson, he said, “We didn’t have things to play with, so we played with lizards and scorpions and snakes and kept them in bottles. Those were our pets.”

This pilgrimage to Manzanar with Prince even has a tinge of the surreal as they come across a black-and-white photo of Bob Nakamura’s second grade class. The picture has been a permanent fixture amongst the archival materials displayed at Manzanar. Almost in disbelief, Prince stares wide-eyed at the photo. To whatever degree Prince has been told about camp is uncertain, but here lies indisputable proof that his Jichan was physically incarcerated there.

In this revelatory moment, grandfather, son and grandson are inextricably linked by Manzanar. It is a moment that also has the possibility of a bit of healing. “He’s been looking for answers himself,” stressed Tad Nakamura. “He has been trying to process and come to peace with not only what happened with camp, but his own identity, his own relationship with his parents and his own relationship with his kids, too.

“Camp became analogous to Parkinson’s,” said Tad Nakamura. “There is no cure to Parkinson’s, just like there is no cure for trauma or racism. So, the goal is how much can you heal along the way? It can’t be cured. But can you heal, can you come to peace with it? Can you at least process it while you’re here?”

These questions are valid but they have no easy answer(s), not for Bob Nakamura and certainly not for his son. Nevertheless, “Third Act” fulfills an epiphany that Nakamura shares in the film, which is,“Less history, more soul.” In changing course in the middle of production when it was obvious that Parkinson’s was already taking a swift hold of his father, Tad Nakamura has transcended the paint-by-numbers quality that plagues most documentaries.

Instead, “Third Act” is less of a portrait of an artist and more a portrait of Nakamura as son, father and grandfather. It is also a portrait of a man with weaknesses and strengths. The godfather of Asian American media is, at his core, a human being who more than deserves forgiveness and redemption.

Tad also realizes “Third Act” is most likely the last film that Nakamura will be working on alongside him as the ravages of Parkinson’s progresses at a steady pace. “One of the north stars throughout this process was what is the film that only I could make as his son. It became this really special time and place where I could sit across from my dad,” Tad said. “I could ask him anything I wanted to know about his life. I asked him all the advice I’ve always wanted to ask. And at the same time, he could tell me everything he wanted to tell me before it was too late.”

“Third Act” had its world premiere earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival and will be screening numerous film festivals this year, including the upcoming Riverrun International Film Festival in Winston-Salem, N.C. (April 14), the San Luis Obispo International Film Festival (April 25, 26 and 28), the Atlanta Film Festival (April 26), Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival (May 3) and the CAAM Fest in San Francisco (May 8). As “Third Act” rolls out, it will undoubtedly garner more attention and accolades as it reaches more festivals and audiences.

Tad Nakamura, however, is more focused on the film’s ability to effect change and engage dialogue about difficult topics such as racism, trauma, illness and the grace inherent in forgiveness and healing.

Tadashi Nakamura and Bob Nakamura in a scene from “Third Act”

Photo: Tadashi Nakamura, Courtesy of THIRD ACT/ COPYRIGHT: ©Tadashi Nakamura

“One of the many things my dad always told me was that the success of your film is based on how useful it is,” Tad Nakamura said, “and so it’s not the merit, it’s not critical acclaim but how much can the community and people use your film. I think hopefully there’ll be a point of connection for people to project their own histories, their own communities, to how racism in this country can really destroy you for multiple generations. I want people to be able to either identify with that intergenerational trauma or that historical trauma, but also my dad is an example of someone who not only has lived through that and is experiencing that, but has also found a way to heal and how to process.

“The reality is that my dad is not going to be around forever, and hopefully, this film will,” he concluded. “I wanted to use the film as a love letter to my dad or thank-you letter. Mainly to thank him for everything that he had done for me. And also to let him know how serious I took his legacy and wanted to carry that on. This is that one film that I felt responsible, obligated and destined to make. And because of that, I think it’ll always be the most important film that I’ve ever made.”