Top photo, from left: Mitchell Matsumura; Marina Shwe Lwin Shyan; Dr. Ethan Huynh; Christina Ku; Rep. Judy Chu (D-Calif.); Dr. Gay Yuen; Matt Weisbly; Dean Z. Pamphilis; Hyepin Im; Heidi Lau; Florence Lin

Bottom photo, from left: Seaton Tsai, Vinh T Ngo, Calif. Assemblyman Mike Fong (D-49th District), Cyndie M. Chang, Justin Kim, Robert S. Chang, Karen Umemoto, Andrew Yam, Gerald S. Ohn and Robin S. Toma. (Photos: George T. Johnston)

The event ties the tragedy to a decades-long pattern of Asian hate, anti-Asian laws.

By George Toshio Johnston, P.C. Senior Editor

(Editor’s note: The following combines Parts 1 and 2 of an article that ran in the April 18, 2025 and May 2, 2025 issues of Pacific Citizen.)

ROSEMEAD, Calif. — Just a day short of a reprehensible act that had taken place four years prior — March 16, 2021 — attorneys, politicians, law professors, community activists and other interested parties gathered at the Rosemead Community Recreation Center in Rosemead, Calif., to commemorate the eight lives — six of which were Asian women — snuffed in a Georgia shooting spree.

That contemporary incident shone a light on a chain of other massacres, as well as lynchings, roundups and anti-Asian legal policies going back more than 150 years, driven then and now by xenophobia, racism, white supremacy, immigration fears, nativism, mass media portrayals and inflammatory rhetoric that resulted in what now gets called anti-Asian violence.

Titled “Remembering: The Atlanta Spa Hate Shootings,” the event packed a plenitude of perspective into four panel discussions: “Atlanta Spa Shootings Remembrance” and “Asian Voices,” running simultaneously, and “Civil Rights & Human Rights” and “Immigration & Birthright Citizenship.”

Before the breakout sessions, though, was a keynote speech by U.S. Rep. Judy Chu (D-Calif.), followed by a short address by California Assemblyman Mike Fong (D-49th District). For the congresswoman, the commemoration of the 2021 tragedy was a teachable moment.

Rep. Judy Chu (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

“Discussions like these help to educate and mobilize our community,” Chu said. She noted that the female Asian victims were, in their lives, “hard-working daughters, mothers and grandmothers. Some were in their 50s and 60s, and one was as old as 74, and they were working hard, simply trying to support their families.”

Chu also noted that what led to the tragedy did not occur in a vacuum. “(When) President (Donald) Trump used the words ‘China virus’ and ‘kung flu’ to describe the Coronavirus in 2020, he fanned the flames of xenophobia.” Then, she said, over the next three years, there were “11,500 anti-Asian hate incidents and crimes reported.

“These were things that were going on all across this country, and we know that the remnants of this are still occurring,” Chu continued. As she wrapped up her talk, she said, “I will continue to combat these discriminatory actions and support Asian American Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders through the 119th Congress and beyond.”

Speaking next, Fong emphasized that “hate crimes against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are not new.” But what led to the Atlanta slayings may have been novel, due to “a backdrop of pandemic isolation, anti-Asian rhetoric from the administration and a steep rise in Asian hate crimes.”

Assemblyman Mike Fong (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

For his part, Fong has tried to take a practical approach. “Here in California, the Legislature has passed the AAPI equity budget, dedicating over $165 million to not only respond to the surge in anti-Asian hate, but also to address long-standing racial inequities that have harmed our community for generations.”

In quick interlude between the speeches, Chu presented half of the participants with congressional certificates of recognition, followed by Fong similarly presenting the others with California State Assembly certificates of recognition.

The “Asian Voices” panel, moderated by Dr. Ethan Huynh, was comprised of Seaton Tsai, a past president of the Asian Pacific American Bar Assn.; Monterey Park Mayor Vinh T. Ngo; and attorney Cyndie M. Chang, a managing partner at Duane Morris LLP.

Taking place simultaneously was the “Atlanta Spa Shootings Remembrance” panel, moderated by attorney Gerald Ohn and comprised of Dr. Karen Umemoto, director of the University of California Los Angeles Asian American Studies Center; Ed Choi, a content creator for TikTok, Instagram and YouTube; Heidi Lau, Hate Program manager at Asian Youth Center; and Esther Young Lim, former chair of the AAPI Advisory Board for the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office.

Dr. Karen Umemoto (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Umemoto began by noting that people of Asian ancestry have been in the United States for more than 200 years and have “grown to a population of 25 million over 50 ethnic groups in over 100 languages” — but in numbers that amounts to just “7 percent of the U.S. total population.” She also related how the latest wave of Asian hate was actually “one of a series of waves,” citing the Los Angeles Chinatown massacre of 1871 as an early, notorious example.

From her perspective, “education is really the key” remedy to counteract anti-Asian violence. “We say Asian American history is American history,” said Umemoto, “but we also say you can’t understand American history without understanding, without seeing it through the eyes of Asian Americans and other groups in this country.”

Umemoto also reported that the UCLA Asian American Studies Center is looking for beta testers for its free online multimedia textbook on the history of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

For Choi, the Atlanta spa shootings reoriented him to use his platform to fight Asian hate — and his contribution to the cause is storytelling and cultural sharing, but in a way that isn’t all “doom and gloom.”

“I started to realize that in order to help eradicate racism, it’s not just about telling our stories, it’s also about being able to show people that we have similarities, that our foods are similar, cultures are similar, families are similar.”

In Lau’s presentation, she referred to a survey conducted by the AYC during the pandemic of 300 people from the San Gabriel Valley. It found that that 31 percent of respondents said they or family members had experienced a hate incident based on their race or ethnicity, with 37 percent of respondents reporting they had noticed an increase in racial discrimination or harassment during that period and 45 percent saying they felt less safe in their community compared to before the pandemic.

Lau also reported that AYC had conducted bystander intervention training, partnering with Asian Americans Advancing Justice. “For the bystander intervention training, we wanted to educate community members to be an ally and also stand up for the community members when they see . . . (a) hate incident happening in the San Gabriel Valley,” she said.

Lin explained how she had created a booklet titled “How to Report a Hate Crime.” Originally written in Korean and intended for her elderly parents, the booklet would eventually be translated into 19 languages and be distributed in six different states.

For Lin, creating the booklet was especially important for the Asian immigrant community members who, for cultural reasons, might be reluctant to report hate incidents because it at least provided a choice. “It’s their right to decline to report because they don’t feel comfortable,” she said. “One thing I learned is that not to push a victim into reporting if it’s against their will because . . . if they are involved in a situation that was out of their control, they want to take some aspect of their life back in their control, so that willingness or unwillingness to report is within their control, and that is their choice.”

On the topic of what constitutes a hate crime, on hand to elaborate on that was Los Angeles Police Department Detective Orlando Martinez. “I know that we call it hate crime, but by law, it’s not hate. They don’t have to hate you, and they can have a protected characteristic themselves. Think of it as bias. It’s just any type of bias,” he explained.

As for what one could do if one were the target of a bias-motivated incident, Martinez gave some options. The first go-to might be to call 911, which, of course, involves law enforcement. “If you don’t want to report to law enforcement, you have LA vs. Hate,” he said, referring to what its website describes as the “community-centered system designed to support all residents and communities targeted for hate acts of all kinds in Los Angeles County.”

Continuing, Martinez said, “You have 211. You just call 211, and you can report these without having to deal with law enforcement. But I want you to encourage your friends and your family to report these things because if we know about it, we can try to do preemptive things to prevent the next person or going through it.”

During the lunch break, more speakers gave presentations. The first was Kasowitz Benson Torres LLP attorney Dean Z. Pamphilis, who described a 21st-century form of anti-Asian violence that came in the form of a lawsuit inspired by a conspiracy theory.

According to Pamphilis, he had been hired to represent Eugene Yu, the CEO of Michigan-based election logistics company Konnech Corp. Pamphilis said Yu was targeted by a pair of election-deniers promulgating a two-related conspiracy theories, one of which was that an unnamed source claimed that 2 million U.S. poll worker records had been found on a computer server that Yu had in Wuhan, China, and that he was “also acting as an operative for the CCP, that he was committing espionage.”

“So, he hired me — I’m a trial lawyer — to sue them. And so I sued them for defamation because everything they were saying was false,” said Pamphilis. Konnech Corp. had contract with Los Angeles County when Yu was arrested in Michigan “on the authority of the L.A. County DA under a sealed indictment.

“We found out that the people who were behind the indictment were in fact the same election deniers that we were suing, that they had been working with the County to bring these charges,” Pamphilis said. Ultimately, in January 2024, Los Angeles County settled, paying Yu $5 million for his 2022 arrest. “The charges were dismissed,” said Pamphilis, who also noted that Yu was eventually declared factually innocent. “But my client’s business was destroyed. He lost over half of his customers.”

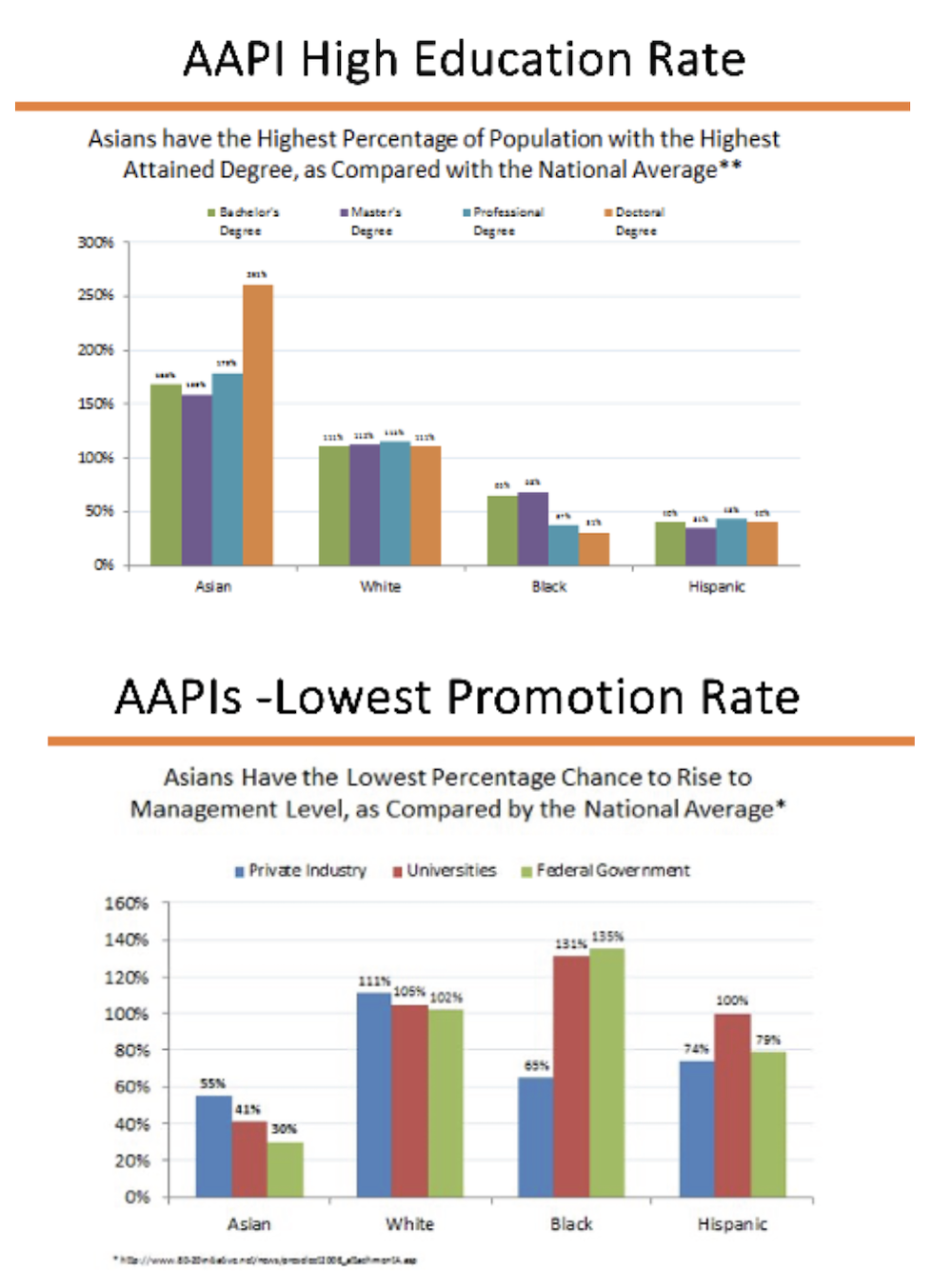

The next lunch-break speaker was Hyepin Im, founder of FACE or Faith and Community Empowerment, whose data-heavy address included several PowerPoint slides. One of her targets: the model minority myth, which she said “does rob our community of needed investments.”

Hyepim Im (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

“Part of the reason why we are perceived as a model minority is because we love education. And you know, everyone thinks and believes — and I think it’s true — education is key to advancement,” Im said. “At all levels, bachelor, masters and professional, we literally surpass any other group, white, Black and Hispanic, so that education investment should translate into success out in society.” Im’s next slide, however, came to a different conclusion.

“Asians have the lowest likelihood of any group of being promoted into management,” Im said. “It does pay off for the Black and Hispanic communities in terms of their probability going into management. But Asians, it actually goes down further.”

Brothers Justin Kim and Ray Kim, entrepreneurs behind a health supplement beverage named the Plug Drink, and Randell Nuguid of the Boiling Crab restaurant chain were next, explaining how they collectively helped raise $100,000 for wildfire relief.

One of next two concurrent panels was “Civil Rights & Human Rights,” which featured Los Angeles County Commission on Human Relations Board Chair Dr. Gay Yuen as moderator and as panelists Asian Americans Advancing Justice Southern California CEO Connie Chung Joe and Los Angeles County Commission on Human Relations Executive Director Robin Toma.

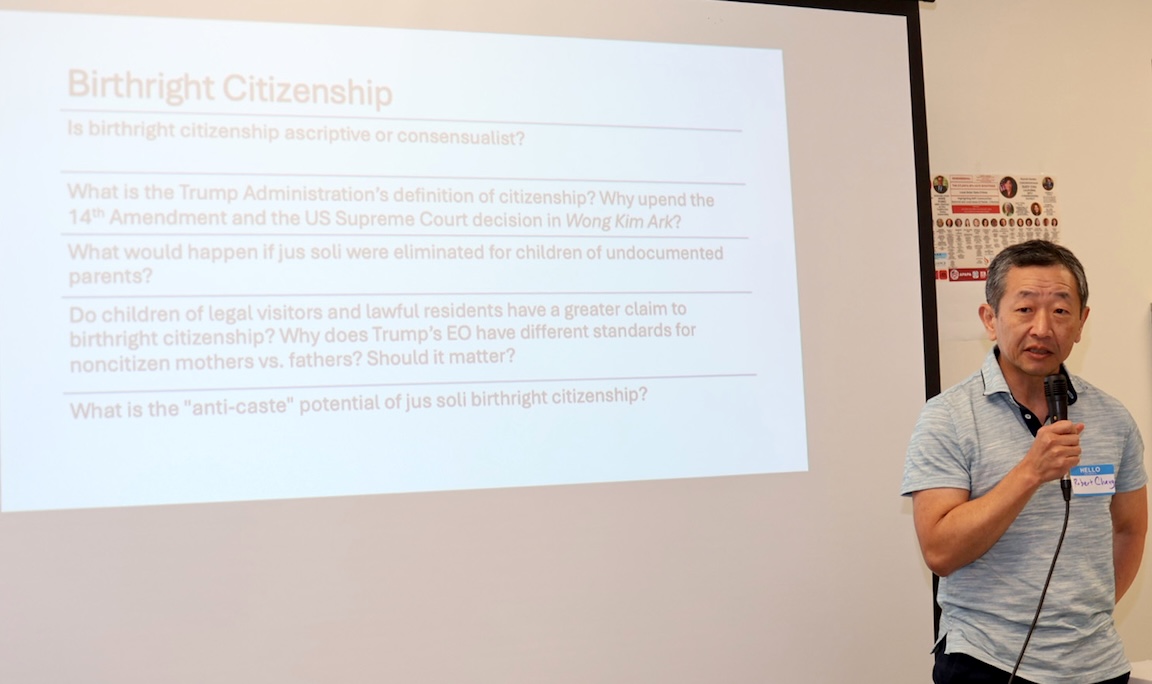

The other was titled “Immigration & Birthright Citizenship,” and serving as panelists were National JACL Education Programs Manager Matthew Weisbly, Loyola Law School Associate Dean and Professor of Law Kathleen Kim and UC Irvine School of Law’s Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality Executive Director Robert S. Chang.

Mitchell Matsumura (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Moderated by Mitchell Matsumura, Greater Los Angeles JACL chapter president, the panel began with Weisbly providing background about something that has been receiving news coverage after the Jan. 20 inauguration of President Trump, namely his use of the Alien Enemies Act. Weisbly noted it was enacted in 1798 when it was one of four laws known as the Alien and Sedition Acts, created when the still-young United States was on the brink of war with France.

Matt Weisbly

“Congress passed these laws to sort of combat any possible enemy aliens or enemy saboteurs who were in the United States at that time,” Weisbly said, noting that politicians were wary of being “taken out from within.” He noted that three of the four parts of the Alien and Sedition Acts “have either expired or been sunsetted,” leaving just the Alien Enemies Act, which has no expiration date. He also acknowledged that until Trump invoked the AEA in January, it had only been used three times: the War of 1812, World War I and World War II, when it was applied to some 2,000 Japanese nationals (who at the time were barred from becoming naturalized U.S. citizens), 1,000 German nationals and 200 Italian nationals.

“Anyone who is not a naturalized U.S. citizen, anyone who’s here in the U.S. without a green card is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and removed,” Weisbly said. “Basically, in a time of war, the president, the government, anybody, can take an alien national or someone who is not a U.S. citizen, and deport them without a trial, without basically without due cause even.”

Although a key part of the AEA is that it may only be used in a time of war — which only Congress may declare — the Trump administration has nevertheless claimed it has the authority to invoke it and deport noncitizens without due process. “There was also a provision that was added later that says that if there is some extenuating circumstances where Congress cannot declare an act of war, that the president can still invoke the Alien Enemies Act without Congress’ approval — which is terrifying,” said Weisbly.

Next up was Kim, author of the 2023 book “Feminist Judgments: Immigration Law Opinions Rewritten.” Her focus for the panel was on the history of legislation and lawsuits as it pertained to Asian Americans and Asian immigration to the U.S., such as what led to the passage of the 13th (elimination of chattel slavery) and 14th Amendments (birthright citizenship and equal protection doctrine) to the Constitution.

Kathleen Kim

She also cited the 1866 Civil Rights Act and 1875’s Page Act, which was designed to prevent prohibit entry of Chinese women — effectively stunting the growth of a Chinese American community by blocking Chinese men laboring in America from marrying Chinese women — into the U.S. by presuming that they were prostitutes and the importance of 1898’s United States v. Wong Kim Ark, a split decision in which the Supreme Court held that U.S. citizenship was conferred upon any person born on U.S. territory.

In Chang’s portion, he discussed several legal cases, such as 1857’s Dred Scott v. Sandford Supreme Court case (which denied citizenship to Black people), the Wong Kim Ark case, 1922’s Supreme Court case Takao Ozawa v. United States, as well as 1882’s Chinese Exclusion Act and 1890’s Naturalization Act.

“The Constitution,” Chang noted, “doesn’t say anything about citizenship. It does say something about naturalization. So, Article One, Section Eight, Powers of Congress, the Congress will have the power to establish a uniform rule of naturalization. And so then what Congress did in 1790 was to pass an act that said that only free white persons could become naturalized.”

Chang said that the Supreme Court’s pre-Civil War Dred Scott decision of 1857 required a change to the Constitution, i.e., adoption of the 14th Amendment, to change that — but he also noted that with regard to Dred Scott, “The U.S. Supreme Court has never overruled it explicitly.”

In 1870, with the Naturalization Act, Congress said, according to Chang, “‘OK, we’re going to change the rules.’ So before, it was just free white persons who could become naturalized. But now, white people and people of African nativity or descent could become naturalized.”

University of California Irvine School of Law’s Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality Executive Director Robert S. Chang in front of a slide explaining birthright citizenship. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

But then in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act barred federal and state courts from granting Chinese persons to U.S. citizenship. However, thanks to the decision in the Wong Kim Ark case, a person of Chinese ancestry born on U.S. soil was entitled to U.S. citizenship. But how was “white” defined, as in the phrase “free white person”? Chang then referred to the 1922 case of Takao Ozawa v. the United States.

Ozawa — a Japanese immigrant who had lived in the U.S. for 20 years — came to the court, and he wanted to be naturalized, asserting that he was actually paler than many so-called white people. It was, Chang said, “an interesting litigation strategy.” When he went to court, Ozawa included as evidence a statement from a cultural anthropologist who had visited Japan and talked about the “white people of Japan.”

“So, he was saying, ‘Well, what is the meaning of white?’ He was contesting ‘whiteness’ and trying to become included as part of that group,” Chang said. “The court looked at him and said, ‘Well, we know that the statute says ‘white,’ and we’re going to understand that as meaning Caucasian. You’re clearly not Caucasian, so you can’t become naturalized.”

Chang then referenced the 1923 case of United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind. “The U.S. Supreme Court kind of put itself in a jam because at the same time, there were these other cases coming along regarding South Asians. South Asians at the time were regarded to be of Aryan ancestry. And so Bhagat Singh Thind, who had also served in the U.S. military during World War I, he came to court and said, ‘I’m Aryan. I’m Caucasian. So, you just last term said that white equals Caucasian.’ . . . That means that you have to let me become naturalized.”

The Supreme Court, however, rejected that argument. “They went back to a ‘common-sense’ notion of whiteness, where he was precluded. Now, there was a real tragedy here because at this time, 60 to 70 South Asians had become naturalized.

“The U.S. Department of Justice had various U.S. Attorney’s Offices around the country institute denaturalization proceedings against them, and over 50 were denaturalized. There were actually a couple courts though that said, ‘No, we’re not going to denaturalize you,’ but in one particular instance, it resulted in a tragedy where the person killed himself, and he said that he has no country to return to.”

Chang then brought up the Expatriation Act of 1907. “So, if a U.S. citizen woman married an alien, somebody who was not a U.S. citizen, she lost her U.S. citizenship,” he said. “But politicians around the country wanted to get voters like women to vote for them, and so they actually repealed part of the Expatriation Act, but it left an infirmity for U.S. citizen women who had married aliens ineligible for citizenship. They were forever barred from regaining their citizenship.”

Chang also noted how those past examples inform today’s executive orders. “There are two categories of people who and according to the executive order, for those born after Feb. 19, 2025, will no longer be recognized as being citizens by birth.

“Now the thing about the executive order is, and this is something that I think people are not paying enough attention to, is that the government is saying, ‘Well, this only applies prospectively.’ But this is wrong because if the executive order is upheld, the constitutional basis [is] for everybody who falls into these two categories.

“So, if you were born to a person who was unlawfully present and the father was not a citizen or a legal permanent resident, then the constitutional basis for your citizenship has gone away. If you were born to somebody who was temporarily here, and the father was not a U.S. citizen or a legal permanent resident, the constitutional basis for your citizenship goes away,” Chang concluded.

When the event wrapped up, because it had gone over the allotted time, organizers dispensed with the candlelight ceremony to honor the Atlanta spa shooting victims.