Emiko (Fukumoto) and Steven Kasmauski flank their son, Stanley Kasmauski (Photo: Courtesy of the Kasmauski Family)

The Smithsonian-backed exhibition puts a unique story on the road.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor

If you were to ask any lay historian about the effects on U.S.-Japan relations since the aftermath of Japan’s surrender to Allied powers that officially ended World War II on Sept. 2, 1945, what might the answers include?

Perhaps how America’s postwar occupation of Japan set the stage for the U.S. to refashion Japan’s constitution. Maybe something about the reformation of its government and land ownership laws. How about the upgrade of women’s rights and the downgrade of its tennō from deity to figurehead? There might also be something about the miraculous economic comeback that turned Japan into both an economic rival and America’s staunchest ally in Northeast Asia.

Less likely to be cited, however, was that between 1945 and 1960, thousands of U.S. servicemen of all ethnicities, creeds and beliefs who were stationed in Occupation-Era and Post-Occupation Era Japan would meet, fall in love with and marry Japanese women.

Although such liaisons were, to put it lightly, officially frowned upon by the U.S. military and by many in both societies, the number of marriages between American servicemen and so-called Japanese war brides in that time period — said have been 45,000 — became a novel societal phenomenon.

With Nisei servicemen stationed in Japan who married Japanese women being an exception, these interracial and intercultural unions (the latter something that did not necessarily exclude Nisei servicemen) would become part of the zeitgeist of that time. Stories of American servicemen bringing home Japanese wives were reported in American newspapers and magazines and would be depicted in pop culture artifacts like the 1952 motion picture “Japanese War Bride,” James Michener’s 1954 novel “Sayonara” (which begat the 1957 movie of the same name) and, peripherally, the 1956 movie “Teahouse of the August Moon.”

Nearly eight decades after the end of WWII, the oft-ignored and overlooked contribution to Asian immigration to the U.S. represented by those Japanese war brides is being recognized as part of a traveling exhibition titled “Japanese War Brides: Across a Wide Divide,” produced by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service and the National Museum of American History.

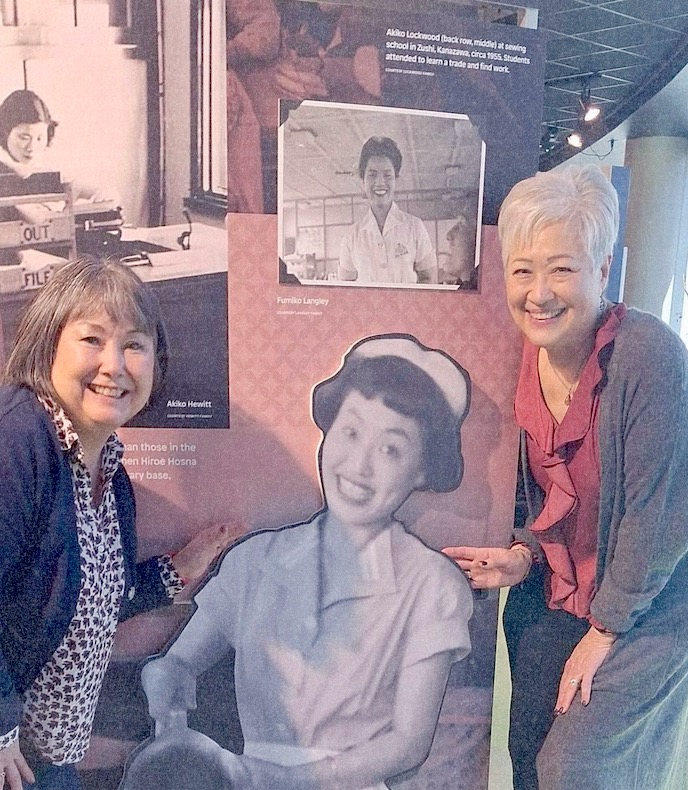

Kathy Hosna Snell (right) was surprised to find a photo cutout of her mother, Hiroe, featured in the traveling exhibition “Japanese War Brides: Across A Wide Divide.” At left is Snell’s friend, Melissa, who is also the daughter of a Japanese war bride. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathryn Tolbert)

With the first stop, which ran from Dec. 14, 2024-April 6 in Texas at the Irving Archives and Museum having wrapped up and the second leg having just begun in Florida at the Morikami Museum & Japanese Gardens in Delray, Fla., “Japanese War Brides: Across a Wide Divide” gives perspective on the obstacles, barriers and challenges these couples — but the Japanese women especially — had to overcome to follow their hearts, and that was often just the beginning of more hurdles yet to overcome.

In addition to barriers to marriage put into place by the military or short-notice transfers out of Japan for the American men and health screenings for the Japanese women that could derail nuptials because of, say, exposure to tuberculosis or allegations of moral turpitude, successfully getting hitched was no easy feat.

This article from Scene magazine — a long-defunct feature magazine that covered Japanese American subject matter — addressed the Japanese war brides phenomenon in its September 1954 issue. (Image: Courtesy of Densho.org)

In time, however, as those barriers were overcome, the Japanese war brides had to then learn how to become American wives (by the standards of the time) via Red Cross courses that taught Japanese women how to cook American food, maintain an American home, act American and more.

Years in the making, the “Japanese War Brides” exhibition is the latest peak in a years-long effort by Lucy Craft, Karen Kasmauski and Kathryn Tolbert — all three daughters of Japanese war brides who married white American servicemen — to document the disparate yet similar journeys that that particular cohort of native Japanese women, now quite elderly if still alive, took so many years ago.

Kathryn Tolbert, standing in front of a display featuring her mother, Hiroko Tolbert, née Furukawa, collaborated with Lucy Craft and Karen Kasmauski on their project titled “The War Bride Experience.” (Photo: Courtesy of Kathryn Tolbert)

For Tolbert, who had nothing but praise for the exhibition’s first stop in Irving, Texas — “They did a beautiful job displaying it” — telling the Japanese war bride story these past several years has been an all-consuming effort that has enabled her to employ her storytelling skills developed as a journalist but also learn new modalities, such as documentary filmmaking (with Craft and Kasmauski, co-producing and co-directing the 2015 documentary “Fall Seven Times, Get Up Eight: The Japanese War Brides”) and web-based storytelling via the website warbrideproject.com.

So, what does a visitor to “Japanese War Brides: Across a Wide Divide” get to see? According to Tolbert, the exhibition has seven free-standing curved panels that contain photographs accompanied by explanatory captions and several interactive touchscreen displays with video stories and an interactive timeline that “deals with the history and the definitions and the legal problems” faced by the Japanese women.

From her wheelchair, Yoko Breckenridge of Minneapolis looks at her barber tools on display as part of the traveling exhibition “Japanese War Brides: Across A Wide Divide.” The story of how she got her license to cut hair in the U.S. and later changed professions to become a real estate agent can be viewed at tinyurl.com/ur5j5sbj. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathryn Tolbert)

It’s worth remembering, for example, that the landmark Loving vs. Virginia Supreme Court case of 1967, which overturned bans on interracial marriages, was still years away. Furthermore, depending on what part of the U.S. one of these couples moved to, whether it was rural or urban, or whether there was an extant Japanese American community, all presented different potential problems. Also, the challenges were different for white-Japanese couples versus Black-Japanese couples. “It tells a lot of very personal stories, and it is focused that way,” said Tolbert, who added, “There’s a big section on family and the range of marriages and outcomes, and these again are told through individual voices, women or their children. It talks about food, it talks about identity, and then it ends with their legacy, and also the fact that children are part of their legacy.”

The Florida phase of “Japanese War Brides: Across a Wide Divide” continues until Aug. 31. It then moves to Louisiana’s Old State Capitol in Baton Rouge, La., from March 21-May 31, 2026, followed by a stay at the Mills Station Arts & Culture Center in Rancho Cordova, Calif., from Dec. 19, 2026-Feb. 28, 2027, with a final stop at the Castle Museum in Saginaw, Mich., from March 18-May 28, 2028.

For Tolbert, Kasmauski and Craft, the effort and time spent working on the traveling exhibition and other war bride-related projects have been both a major accomplishment that paradoxically has only begun to tell the stories of Japanese war brides.

“What’s great is that there are a lot of students who are tackling this subject,” Tolbert told the Pacific Citizen. “So, we’re hoping that the exhibition, as it travels, will encourage more family storytelling because we have only scratched the surface.”

Bride and Prejudice?

‘Picture Bride, War Bride’ gives voice to different waves of Japanese women.

By Curtiss Takada Rooks, P.C. Contributor

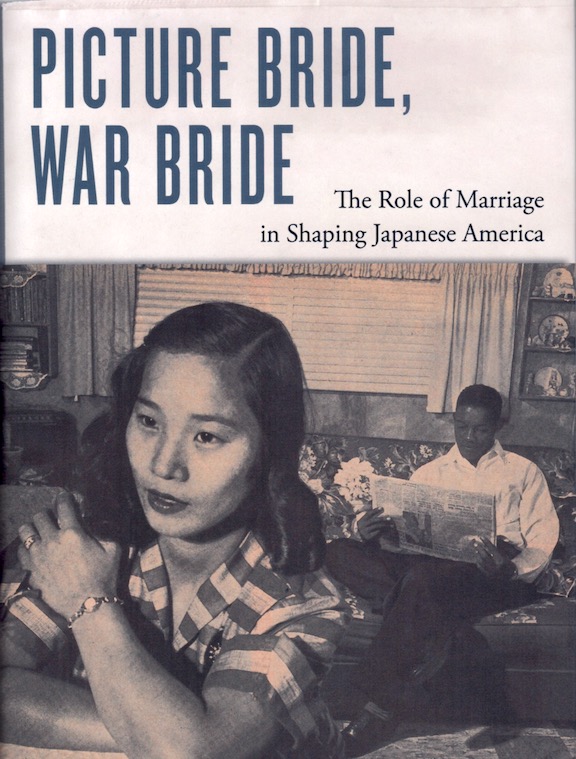

In “Picture Bride, War Bride: The Role of Marriage in Shaping Japanese America” (ISBN-13: 978-1479803071, NYU Press, 2024, 200 pgs., SRP: $35), author Sonia C. Gomez — an assistant professor of 20th-century U.S. history at Santa Clara University — provides a much-needed and largely overdue testimony of women’s voices in Japanese American history.

Given gender and cultural power dynamics, “history” has been generally viewed through the lives, experiences and views of men — and this is particularly true of Japanese American histories that have focused on the predominantly male migration of Issei during the Meiji Restoration, resulting in a heavily imbalanced immigrant community. These histories focus on telling the story of Issei men as agricultural labor, small-business owners and community leaders.

Given gender and cultural power dynamics, “history” has been generally viewed through the lives, experiences and views of men — and this is particularly true of Japanese American histories that have focused on the predominantly male migration of Issei during the Meiji Restoration, resulting in a heavily imbalanced immigrant community. These histories focus on telling the story of Issei men as agricultural labor, small-business owners and community leaders.

In broad 19th- and early 20th-century Asian American histories, mention of women migrants too often focus on them as exploited domestic laborers and/or sex workers. Nor do these Japanese American histories explore how the presence of Japanese women was perceived in the gender politics of the time served to domesticate Issei men, serving a dual purpose of proving their potential for assimilation, while protecting the virtue of white women. In short, these histories tell us a particular “story” about Japanese immigrant women, but not necessarily their stories and voices.

Gomez’s “Picture Bride, War Bride” joins Akemi Kikumura’s “Through Harsh Winters” and Evelyn Nakano Glenn’s “Issei, Nisei, War Bride” in elevating Japanese immigrant and Japanese American women’s experiences and voices. But Gomez does more than simply write these women “into history”: She deftly argues their centrality in 1) the formation of Japanese American communities through their demographic, social, cultural and economic contributions; and 2) the roles these Japanese immigrant women played in various processes of race and interracial relationships.

Throughout her analyses, Gomez, whose maternal grandmother was a Japanese war bride, leans heavily on notions of inclusion and exclusion both within the Japanese American community and broader American multiracial landscape, centering individual stories as an illustration of larger cultural, social and political processes. She unveils the vital roles played by these Japanese women in establishing economic stability for the Issei family and with it the burgeoning Japanese American economy beyond agricultural wage labor.

Indeed, Gomez points out that Issei women’s field labor constituted an economic threat to Irish and other white farmers by giving the Issei men unfair advantage. Why? Because by using the labor of their wives (and later their children), they did not have to hire as many migrant laborers.

In many respects, Gomez argues that the “unpaid” Issei women’s and Nisei children’s labor in family agricultural and small business enterprises served as economic multipliers, solidifying economic stability and success for the Issei.

By 1920, when the Japanese government stopped issuing picture bride passports and with the passage of the 1924 Immigration Act, which virtually halted all Japanese (and Asian) migration to the U.S., the picture-bride phenomenon became a historical artifact. It would take the end of World War II to create a new wave of immigration from Japan.

From 1945 to the early 1960s, Japanese war brides would constitute the largest cohort of Japanese immigrants to the U.S. According to the Smithsonian Institution’s traveling exhibit “Japanese War Brides: Across a Wide Divide,” unveiled in December 2024 in Irving, Texas (see main story), the nearly 45,000 Japanese women who married U.S. servicemen stationed in postwar Japan had by 1960 increased not only the Japanese American population but also the Asian American population by 10 percent.

Yet, too often in the telling of Japanese American history, this cohort appears almost as an “footnote,” Japanese but not Japanese American, thus essentializing the traditional Japanese American narrative as the authentic Japanese American story.

Gomez remedies this with her examination of the lives of the Japanese war bride women and their families, providing a window into narrowness of the Japanese American community’s sense of inclusion, as well as its racialized attitudes toward other nonwhite American communities.

Of particular interest for me, as the child of a native Japanese mother and African American father, is Gomez’s examination of Japanese war brides who married Black servicemen. Gomez situates their lives within an understanding of broader Afro-Asian solidarities, providing an argument on the impact and influence of Black soldiers, sailors and airmen on Occupation Era and Post-Occupation Era Japan and the ideals of civil rights, including the expansion of Japanese women’s rights.

While focusing on Camp Gifu as a site for the relationship between Japanese women and Black soldiers, it provides a template excavating similar understandings, explorations and analyses of Japanese locations such as Okinawa and Camp Zama (Yokohama) where my parents met and married.

In centering on picture brides and war brides, Gomez asserts the primacy of the role of marriage and family in the formation of “Japanese American.” In this monograph, Gomez also asks about and gives insight into the lives of Issei men who never married. As with the women’s stories and the narratives surrounding these Issei men’s lives, she not only gives them a voice but also provides deeper insights into Japanese American gender, family and sexuality.

While aimed at scholars and lay historians, Gomez’s “Picture Bride, War Bride: The Role of Marriage in Shaping Japanese America” is, I believe, of great importance to the Japanese American community writ large.

Gomez, as she intends, brings to our understanding and consciousness the lives of those rendered to the “margins” of our stories about the Japanese American experience. In doing so, she allows all of us a fuller and more complex story to tell.

Curtiss Takada Rooks, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at the Asian and Asian American Studies Department of Loyola Marymount University.