Three children pray at the Cenotaph in Hiroshima Peace Park on Aug. 12, 80 years after the bombing of Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. (Photos: Darrell Miho)

It’s been 80 years since humanity turned against itself,

but with hope and resilience, the world must learn to do better.

By Darrell Miho, P.C. Contributor

It has been 80 years since atomic bombs were detonated in Japan over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Eighty years since humanity turned against itself. In those 80 years, leaders of the most-advanced countries have learned nothing about how to live in peace. Nuclear weapons are now up to 250 times more powerful than the bomb that was used in Hiroshima. With more than 12,000 nuclear warheads worldwide, humanity is just a push-of-a-button away from the end of the world as we know it.

On Aug. 6, more than 40,000 people descended upon Hiroshima Peace Park for the annual Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony. One of those in attendance was Junji Sarashina, a Lahaina-born hibakusha (bomb-affected person), now living in Buena Park, Calif., who moved to Hiroshima with his family when he was 8 years old.

August 6, 2025; Hiroshima, JPN – 80th Annual Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony in Hiroshima.

After the ceremony, atomic bomb survivor Junji Sarashina stops to pray for the victims and say goodbye to his beloved wife, Kiyoko Sarashina, whose name was added to the cenotaph at this year’s ceremony.

Sarashina-san was 16 years old and 1.5 miles from the hypocenter when the atomic bomb, named the “Little Boy,” unleashed the force of 16 kilotons over Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. Ironically, he was working in a factory building artillery shells for the Japanese war efforts. He was knocked unconscious by the blast, but luckily, he did not sustain any major injuries.

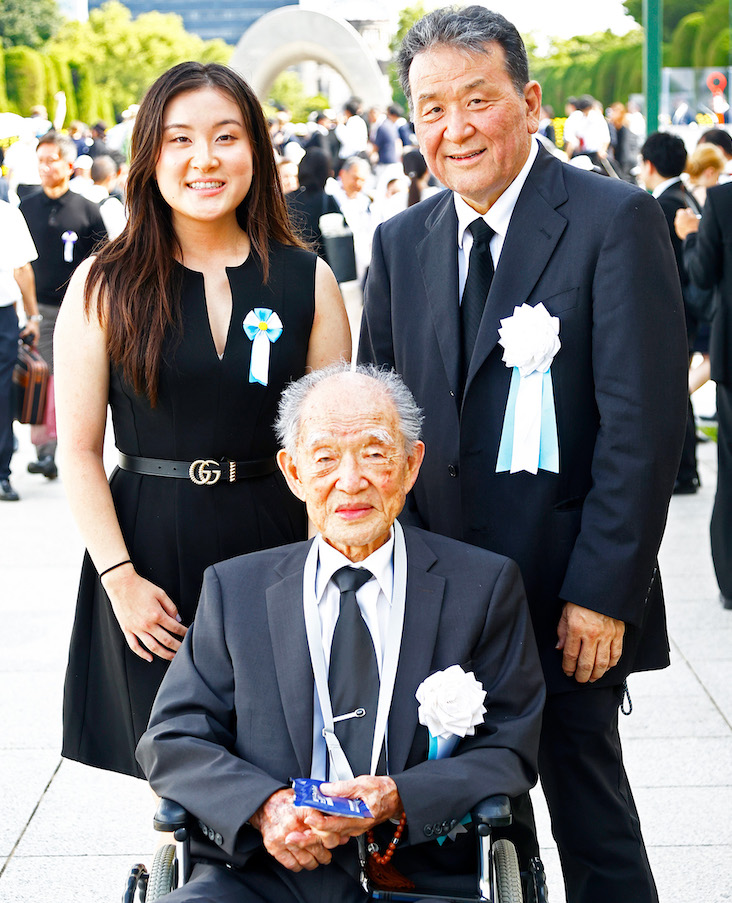

He attended this year’s ceremony as a guest of the city of Hiroshima, along with his son, James, and his granddaughter, Emily. James was there to represent his mother, Kiyoko Sarashina, who was also a hibakusha, who unfortunately was tragically killed in a car accident two years ago. They all shared tears as they remembered her — wife, mother and grandmother.

Sarashina-san has mixed emotions about being in Hiroshima for the 80th annual ceremony. While he enjoyed returning to the city where he spent his childhood, the painful memories of that fateful day are seared into his memory. As Junji Sarashina talked about his experience, he retold his story with such clarity — as if it happened yesterday.

“What I’ve seen is something unimaginable,” he recalled. “The tremendous explosion, buildings collapsing, the bright glows of rays and heat. The whole city is burning. The only thing you can see is the flame and smoke — smoke so thick that you can hardly see the city itself. When I tried to go into the city, that’s when I saw many victims, burned people, no face, no hair, no clothes, skin burned, bleeding, wounded, some of them wandering aimlessly.”

Emily and James (standing) and Junji Sarashina pose for a photo after the ceremony with the Cenotaph and Genbaku Dome in the background on Aug. 6 in Hiroshima, Japan.

As president of the American Society of Hiroshima-Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Survivors, Sarashina-san has told his story countless times over the years to students, adults, church groups and many others to remind people of what he calls “the living hell” that he lived through.

After the ceremony, we all sat together in a coffee shop and talked about how Sarashina’s story is different from most other hibakusha’s stories. He is a U.S. citizen, he survived the atomic bomb and he served in the Korean War in the Military Intelligence Service. Emily reminded us of the strength and resiliency her grandfather has, yet, Japanese American hibakusha stories have received little recognition.

We need to honor the hibakusha the same way we honor the 442nd/100th. We need to remember their stories the same way we remember the incarceration of people of Japanese ancestry during World War II. There will come a time when there will be no more hibakusha left to share their stories, and that time is coming soon. The average age of hibakusha is 86. ASA only has one member left who shares his story regularly, and he recently told me he is ready to retire.

The stories themselves are powerful reminders of the destructive force nuclear weapons have on not just the land but also on people’s lives. When Sarashina-san recounted his story, he talked about wandering the streets of Hiroshima for three days because he was unable to go home due to all of the debris that blocked the roads and train tracks.

One of the vivid memories he talked about is how he saw a black ball, a child, curled up on the ground, cradled by the mother. The child was burned so bad, he doesn’t even know if it was a boy or a girl. He saw 5,000-6,000 dead bodies. No 16 year old should witness such horrible sights, but Sarashina-san did. He tells his story again and again, not because he wants to remember those horrific days, he tells them so that we never forget.

Any visit to Hiroshima should include two places, Miyajima, designated by the Japanese government as one of the three most beautiful places in Japan, and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, a stark reminder of the devastation that destroyed a city and the lives of the people who lived there. The two places are polar opposites of beauty and destruction.

A mother and her son look at a large mural on Aug. 12 showing the destruction of the Genbaku Dome and the surrounding area after the bombing in Hiroshima.

The museum underwent a major revision of its exhibition area and reopened in 2019. There are many new photographs, murals, artifacts from the destruction and artwork created by the survivors, but most importantly, there are more displays of personal belongings accompanied by stories of the deceased. Visitors learn about the people of Hiroshima.

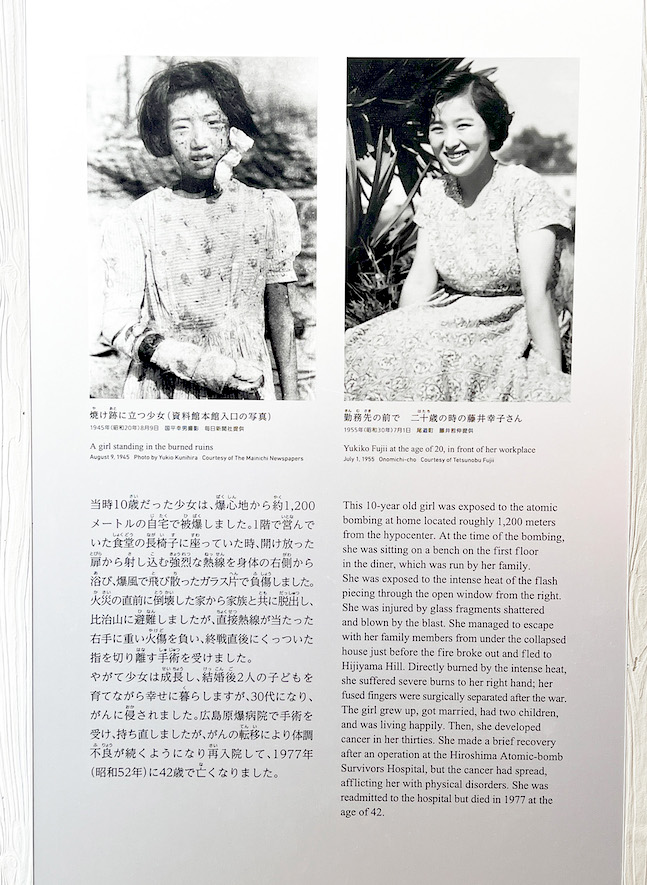

One of the displays in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum shows two photos of Yukiko Fujii. One was taken on Aug. 9, 1945, shortly after the bombing, and the other is 10 years later on July 1, 1955.

The day I visited the museum, five days after the ceremony, the line outside was long, and the museum was packed, but inside there was almost utter silence. The only sound one heard was shuffling feet and sniffles from those overcome with emotion. Children and adults were all respectfully quiet as they absorbed the sorrow of the stories and exhibit.

After the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony, thousands of people line up to pay their respects at the Cenotaph, where the names of those who are deceased are placed.

It’s an emotional experience learning about the lives of the people who were affected. It’s a major shift from the previous exhibit, which focused on the physical destruction of the city. The current exhibit, with more personal belongings and stories, will create a stronger connection with visitors and, as a result, bring more awareness about the devastating affects that nuclear weapons have on people’s lives.

As one of ASA’s directors and someone who has met with more than 400 hibakusha around the world, I have heard countless stories from survivors, who mostly declined to be interviewed on camera, yet still took the time to tell me about their experience.

Stories of hardship, loss and overcoming tremendous odds and having to do things that no child should have to do, like being tasked with cremating bodies. I made a promise to them that I would continue to tell their stories so that we never forget their pain and suffering and continue their fight for a world free of nuclear weapons.

Hundreds of people release lanterns along the riverbank of the Motoyasu River to pray for peace and honor the victims and survivors of the atomic bombs.

If there is one thing that we can learn from the hibakusha, it’s forgiveness. Despite surviving one of the most heinous crimes against humanity, none of them hate America, not that they never did, but over the years as time has passed, they have learned that it is more important to live in peace rather than hold a grudge. They chose forgiveness over vengeance. Peace over anger. Their hope is that no one ever has to experience the “living hell” they went through.

We all want peace in the world. We all want peace in our lives. It all begins with peace in our hearts. The bombs may have ended the war, but 80 years later, the silent battles the hibakusha face and their outward fight for the abolishment of all nuclear weapons continues to this day.

It is now our responsibility to carry on their fight for world peace. We must continue to share their stories for the same reason that Sarashina-san does, so that future generations never forget. Peace begins with us.

This article was made possible by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL Redress Strategist Grant Ujifusa. To make a donation to this fund, email busmgr@pacificcitizen.org and put Honda Memorial Journalism Fund in the subject line.