Entry to the Redondo Beach Veterans Memorial in February 2025; note that the concrete base in the center is missing its plaque. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Plaque commemorating Dr. Tsuyoshi Okada is replaced in time for Veterans Day.

By George Toshio Johnston, P.C. Senior Editor

In January, Douglas Okada was at the Redondo Beach Veterans Park to teach a martial arts class when he made a disquieting discovery: The park bench at the park’s Veterans Memorial that he had helped pay for years earlier to commemorate his father, Tsuyoshi Okada, M.D., was gone.

Yes, the bronze plaque that was embedded in the concrete bench had been chiseled out, leaving an unsightly, empty space.

To say that the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agent was shocked by the desecration to his father’s memory would be an understatement. That this bench — the only one with Japanese first and last name — was the only one among the so-targeted immediately made him wonder whether there was also some sort of anti-Japanese or anti-Asian animus at play.

Regardless, Douglas Okada was determined to have the plaque honoring Tsuyoshi Okada replaced. Getting that accomplished would not, however, be a simple task.

Who Was Tsuyoshi Okada?

The story of Tsuyoshi Okada’s life was both unique to him but also similar to those in his cohort of second-generation Americans of Japanese ancestry. He was the eldest among the three sons of Kanichi Okada, an Issei from a Japanese farming family and himself an eldest son, who came to the United States to seek his fortune farming here, landing in California’s Salinas Valley, rather than taking over his father’s farm in the Old Country.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the family voluntarily evacuated to Colorado, settling in Fort Morgan to begin farming again. Those cold Colorado mornings and farming did not, however, agree with Tsuyoshi Okada, who decided that education was his way out. He went on to the University of Colorado at Boulder to study chemistry, graduating at the top of his class, then to Northwestern Medical School in Chicago, paid for with proceeds from his father’s successful sugar beet farming operation, which had a contract to provide sugar for the Army.

Douglas Okada, who works as a Customs and Border Protection agent, is shown in February next to the bench that had contained the plaque commemorating the military service of his father, Tsuyoshi Okada. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

In Chicago, as he studied medicine, he also furthered his commitment to Christianity by studying at the Moody Bible Institute. Although the Army wanted to draft him as a student, he made a promise that he would serve as a physician after completing his medical studies, which he did, eventually serving as a doctor stationed at Camp Zama treating soldiers injured in the Korean War but also serving as its base commander.

Tsuyoshi Okada’s civilian medical practice began after his honorable discharge. He brought his family to settle in Torrance, Calif., where he began his internship and residency training at Harbor General Hospital, now Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

That would lead to a 46-yearlong medical practice, with Okada serving patients in Southern California’s South Bay: Gardena, Torrance, Redondo Beach, Manhattan Beach, Palos Verdes, Rolling Hills and Los Angeles. Initially, like other Nisei trying to make an honest living and despite his educational achievements and military service, Okada had to overcome not just the usual “anti-Oriental” sentiment that was then the norm, there was still a lot of post-WWII anti-Japanese sentiment.

As Douglas Okada noted, “The Caucasian physicians did not want any Asian, African American, Hispanic or Jewish doctors practicing medicine in the South Bay but especially Palos Verdes and Torrance.”

According to Okada, the American Medical Assn.’s board certification testing was conducted with one week of written examinations and one week of oral examinations. “The Caucasian local physician specialists would fail anyone of color or a different ethnicity that would attempt to pass the oral part of the American Medical Assn. Board Certification tests,” he wrote.

However, because of his father’s “near-photographic memory and intelligence,” they could not fail him. Furthermore, according to Okada, the American Medical Assn. “realized how the oral examinations were being abused, and they ended that type of testing.”

The Case of the Stolen Plaque

This statue of Sontoku Ninomiya at the corner of Second and San Pedro Streets in Little Tokyo used to have a metal plaque attached to its base. It was stolen decades ago. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

So, Douglas Okada wanted to pay tribute to his father in the years after his death by paying for a bench and commemorative plaque to honor his memory and military service during both the Korean and Vietnam Wars.

As it turned out, however, the theft of the bronze plaque was likely the modern-day scourge of opportunistic metal theft, not anti-Japanese or anti-Asian sentiment, as there were also other bronze plaques with no Asian names that were also stolen, as well as still-intact plaques with Japanese names on them.

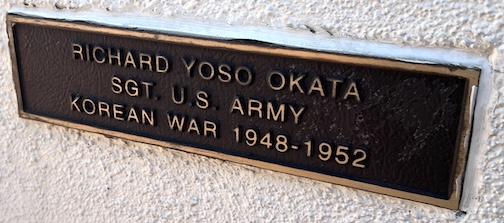

The plaque for Richard Yoso Okata, also a Japanese American like Tsuyoshi Okada, was not stolen. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Although it is nothing new — the bronze plaque on the statue of Sontoku Ninomiya in Little Tokyo was stolen decades ago — in recent years there have been dozens of news accounts of people having their catalytic convertors sawed off their Toyota Priuses, copper wiring stolen from municipal streetlights, bronze nameplates at mausoleums getting stolen, etc. It became so bad in Los Angeles that the city created a “copper wire task force.”

That it was more likely a case of metal theft and not anti-Japanese sentiment would be small consolation for Douglas Okada. The plaque was still gone.

Indications several months ago were that the city of Redondo Beach would have his father’s plaque restored by Memorial Day last May, this time with less-expensive aluminum instead of bronze. But that didn’t happen.

Even on Nov. 7, a visit to the Redondo Beach Veterans Park showed that the bench plaque honoring Tsuyoshi Okada was still missing — and Veterans Day, Nov. 11, was looming.

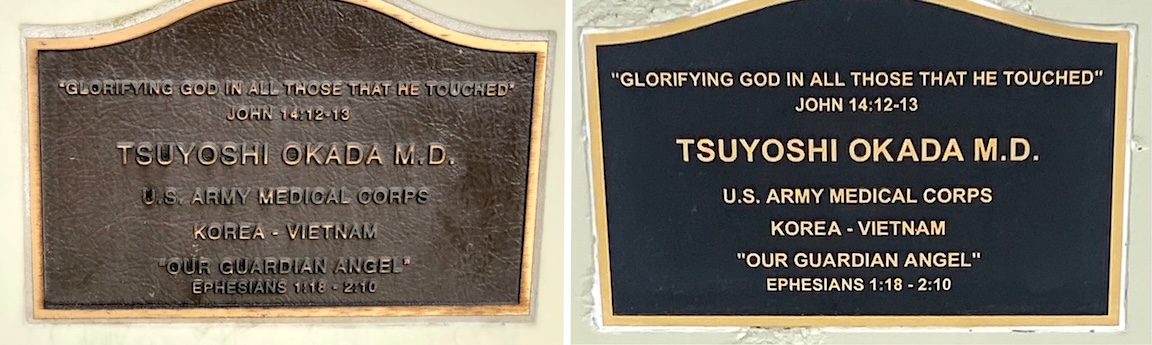

The original plaque, left, and the new plaque right (Photos: Courtesy Of Douglas Okada and Tom Lasser)

But on that Tuesday, just in time for Veterans Day, the plaque was back. It was a happy ending to a worrisome, distressing story that Douglas Okada no doubt hopes does not have a sequel.

(Editor’s note: Tom Lasser of the Redondo Beach Veterans Memorial Task Force contributed to this report.)