Pilgrims visit “America’s Last WWII Concentration Camp” exhibit at the My Story Museum. (Photos: Rob Buscher)

By Rob Buscher, P.C. Contributor

Almost one year ago during the week of the November 2024 election, I journeyed to rural South Texas to help the Crystal City Pilgrimage Committee open a public history exhibit on the wartime incarceration at My Story Museum.

At the time, I felt slightly apprehensive boarding an airplane from my home city of Philadelphia to Texas less than 48 hours after the highly polarizing election.

Days earlier, the New Yorker published a clickbait think piece titled “The Americans Prepping for a Second Civil War,” which included stories about people on either side of the political divide who were stockpiling guns and ammunition for what they saw as inevitable violence stemming from the election.

The media fervor made it seem like we were on the brink of open conflict between progressive urban coastal areas and the conservative rural interior regions of the country. I was honestly unsure what to expect when I arrived in Texas to spend four days in Crystal City for the first time.

Crystal City itself is largely progressive as the birthplace of La Raza Unida Party — the progressive third party that sought to give political voice to the Chicano movement of the 1970s.

During the grand-opening ribbon-cutting ceremony that took place in November 2024, we were greeted by a crowd of about 250 rural Texans who enthusiastically welcomed our small committee of Japanese American incarceration survivors and descendants.

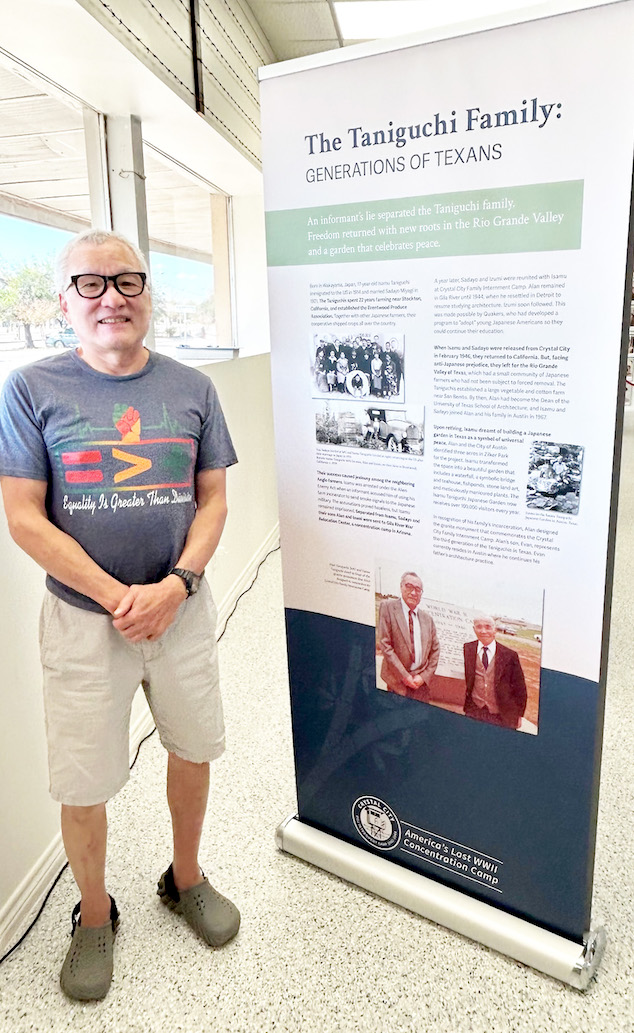

Austin, Texas, resident Evan Taniguchi poses next to his family’s banner at the museum.

There, I met Mexican American community elders and heard their stories about the 1969 student walkout, directly from the people who lived it. At restaurants and small businesses, local residents went out of their way to say hello and make us feel at home in their community.

I left Texas with a renewed sense of hope. If such a community could exist in South Texas, surely there must be others like it elsewhere in rural America.

Now, nearly one year into the second Trump presidency, I had the opportunity to revisit Texas during the 2025 Crystal City Pilgrimage that took place Oct. 9-12 in San Antonio and Crystal City.

What I saw and experienced there has continued to fuel my optimism in the organizing potential of rural America and the role that our Japanese American community might play in bridging the urban-rural divide.

Members of the Crystal City Pilgrimage Committee

This year’s pilgrimage theme was “Crystal City Rising — Neighbors Not Enemies,” chosen in reference to the legislation first introduced in 2020 by Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) that, if passed, would repeal the Alien Enemies Act of 1798.

The pilgrimage’s co-chairs, Hiroshi Shimizu, Gabriela Nakashima and Brian Shibayama, offered more context in their welcome letter, stating “[The theme] honors the solidarity and community between the people on both sides of the Crystal City Family Internment Camp barbed-wire fence. This sense of community and friendship has continued through the years, and we are deeply grateful for the partnership and support of our Crystal City friends as we continue this pilgrimage work.”

The pilgrimage co-chairs continued, “At a time when we are seeing rampant anti-immigrant rhetoric and direct parallels to our own history, we must uplift and preserve our stories, build across communities and movements and stand in solidarity together.”

“Alien Enemies Act” panel participants (from left) Katherine Yon Ebright, Jennifer Ibanez Whitlock, Grace Shimizu and Larry Oda with moderator Rob Buscher (back row)

As a Department of Justice detention site that specifically imprisoned individuals arrested under the Alien Enemies Act, the history of Crystal City is uniquely suited to draw comparison with what is happening amid the nationwide expansion of ICE detention and militarized immigration enforcement.

The pilgrimage program was designed to emphasize these direct linkages in a way that commemorated the experiences of incarceration survivors, while also demonstrating actionable strategies for pilgrims to get involved in advocacy work to support immigrant communities today.

In its curation of the program, the committee also prioritized content that would further the connections between local histories of the Chicano Movement and the Nikkei diaspora.

The pilgrimage consisted of two full days of programming, starting with a day of educational workshops in San Antonio, followed by a visit to Crystal City.

Nearly 200 people attended the events, with some traveling from Japan, Peru and Canada — in addition to local Texans and Japanese Americans from across the country.

The program opened with remarks from Bexar County Judge Peter Sakai, a Sansei and third-generation Texan whose grandparents were among the first Issei farmers in the Rio Grande Valley.

San Antonio Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones also welcomed the pilgrims to her city. Having assumed office in June 2025, Jones is herself an indication of the changing demographics of Texas as both the first Asian American (Filipino) and openly gay mayor of San Antonio.

CCPC member Karissa Tom then offered their own remarks connecting the past to the present and underscored the relevance of Crystal City to current events.

This messaging was consistent with remarks delivered by speakers who participated in an incarceration survivor panel that featured Japanese Americans, Japanese Peruvians and German Americans.

Following this, a second plenary titled “Manufacturing Enemies: The Alien Enemies Act Then and Now” addressed current efforts to repeal the AEA. The plenary included legal scholars, policy experts and grassroots advocates. Among the speakers was JACL National President Larry Oda, himself a Crystal City survivor.

CCPC board member and local Crystal City resident Ruben Salazar speaks to pilgrims at the high school.

Workshops held during the second half of the day explored the Ireichō, which was brought to Texas by Rev. Duncan Ryuken Williams and his team, and the ongoing collaboration between CCPC and My Story Museum.

A second workshop track explored the Chicano Movement in South Texas that featured several members of La Raza Unida Party.

Presented in tandem was a workshop led by Campaign for Justice that explored current efforts to achieve redress for Japanese Latin Americans.

That evening, the pilgrimage hosted a celebratory event called the Peru-Kai, which offered an opportunity for pilgrims to share their performance talents as the attendees enjoyed dinner and informal socialization.

Pilgrims and locals join together for an intergenerational dance.

I had the opportunity to perform guitar and co-lead several bon odori dances during the Peru-Kai, which reminded me that amidst the difficult work of organizing, we must also make space for joy. Our Mexican American friends in attendance greatly appreciated the opportunity to experience Japanese cultural traditions.

The next day, my visit to Crystal City commenced with an interfaith memorial service held at the site of the swimming pool where two Japanese Peruvian girls drowned in 1944.

Flower offerings at the Crystal City camp monument

With religious observances led by Williams and Christian Pastor Dino Espinoza, the memorial also featured remarks by Crystal City Mayor Jose Angel Cerda, City Clerk Sandra Zavala and members of the city council and school board. As part of the ceremony, local officials were asked to stamp the names of several Crystal City incarcerees in the Ireichō.

Local residents then hosted lunch at Crystal City High School, where pilgrims were able to view the photo exhibit by Crystal City native Hector Estrada that first debuted at the Spinach Festival in 2012.

Pilgrims then took turns visiting the My Story Museum and touring what remains of the prison site. There was also a workshop about immigrant rights led by Amerika Garcia Grewel, co-founder of Border Vigil – a group that hosts monthly vigils for migrants who died while attempting to cross the border, advocating against further militarization in immigration enforcement.

I spent most of that day at the My Story Museum to help support the local docents by answering questions that pilgrims had about the newly renovated exhibit. It was gratifying to welcome members from six of the eight families who were profiled in the exhibit as they saw their stories incorporated into a museum setting for the first time.

The closing day of the pilgrimage took place in San Antonio and featured a half-day program that gave attendees actionable ways to get more involved in advocacy work. This included presentations from Tsuru for Solidarity and Natalie Sanchez-Lopez, executive director of the Latino Texas Policy Center.

In the month or so since the pilgrimage ended, I have found myself returning to the question of what change might be possible with sustained engagement by coastal urbanites in rural regions of the U.S.

As a country, the U.S. feels more divided today than any moment in recent history. Although there have been major divisions across segments of our population since the birth of this nation, in recent decades, both sides of the aisle have created a zero-sum, all-or-nothing approach to governance.

The extremity of partisan politics has created a political culture where compromise is viewed as weakness, and loyalty to the party is valued over collaboration that might lead to positive change for society.

In the context of overcoming the urban-rural divide, sharing physical space with someone of a different background creates the potential to better understand perspectives outside of our own.

Acknowledging our shared humanity, we must work to see each other beyond the context of mediatized stereotypes propagated by individuals on both sides of the divide.

In doing so, this may reveal mutual goals that we can work toward together for the betterment of our society.

As a public historian, I have spent a great deal of time in rural, conservative and often impoverished communities where Japanese Americans were incarcerated during WWII. I believe that such communities long-forgotten by the coastal elite of both parties are rife with opportunity to build coalitions that may one day heal the divide.

CCPC board members Victor Uno, Hiroshi Shimizu, and Kaz Naganuma with former Crystal City Mayor Frank Moreno and former City Manager Felix Benavides

I see the work that CCPC is doing as an opportunity to measure the impact of this strategy, as we continue to build and strengthen relationships with local residents in our shared effort to preserve the history of Crystal City.

The camp exhibit at My Story Museum provides a physical site of exchange and connection between our communities. Pilgrims who knew little of the Chicano Movement history in Zavala County left the museum with an understanding that state violence and institutional racism has shaped the Mexican American community in similar ways to the Japanese American community.

Regional audiences and Crystal City residents have also come to see the wartime incarceration as an important part of their own local history, as the exhibit demonstrates that much of the town’s current infrastructure was built on the remnants of the prison camp. Crystal City residents have become a compassionate witness to the wartime history of Japanese Americans, as we have to theirs.

A 3D camp model at My Story Museum

Each region of the country possesses distinct local histories that impact the ways our wartime experiences are understood. That also means that the specific points of intersection with local communities are all slightly different.

Given that the population of Crystal City is over 90 percent Hispanic, Crystal City offers unique opportunities for mutual connection and understanding compared to other regions where Japanese American confinement sites were located.

However, even in places with a conservative white majority, I believe there are still opportunities to build genuine connections around shared values and begin dismantling the manufactured political divide.

The theory of change for this work has yet to be fully tested, as the Crystal City exhibit has only been open for just over a year. Whether this will lead to lasting impact in the region is yet to be seen. In a limited sense at least, the success of the recent pilgrimage has demonstrated that it is possible to transcend the urban-rural divide as we continue to deepen the organizing relationship with our friends in Texas.