Bruce Sunada in action on the lanes. (Photos: Courtesy of Gil Asakawa)

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

Japanese Americans love bowling.

JAs have been bowling since the early 20th century. But the ancient (invented by the Egyptians!) sport was formalized in the U.S. with rules by the American Bowling Congress in 1895, and those rules excluded anyone but white players. Though JAs played where they could in unofficial lanes before World War II, the war didn’t allow for expensive alleys in the concentration camps. Baseball, football, basketball and even sumo, yes. But not bowling.

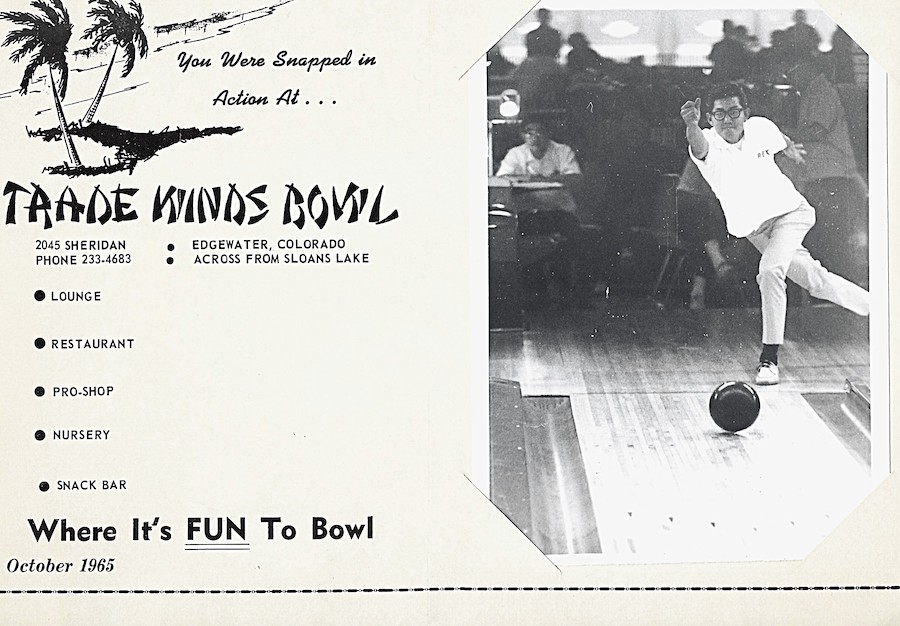

Rex Yoshimura in the Trade Winds Bowl 1965 program

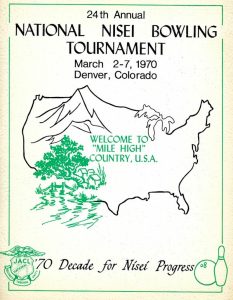

Program for the 1970 National Nisei Bowling Tournament

After the war, JACL filled the exclusion gap and hosted the first National JACL Nisei Bowling Tournament in 1947, and the organization’s circuit criss-crossed the U.S. until 1974. Even though the ABC was forced to allow bowlers of color in the early 1950s, JAs’ love for their own leagues had been established. Regional associations for Nisei leagues formed like the Southern California Nikkei Bowling Assn. in 1955, and national tournaments were held every year.

A program book for the JACL National Nisei Bowling Tournament, held the first week of March 1970, lists hundreds of bowlers from across the country, converging on Celebrity Sports Center in Denver for a week of camaraderie and competition. The program lists previous champions and winning teams, as well as includes ads from leagues and JA-owned businesses from the Denver area and greetings from Seattle, San Jose and Southern California leagues.

1970 Tournament Greetings

Bowling was so popular with JAs in the early 1970s that JACL decided to spin off the management of the sport to a separate organization. JACL was increasingly focusing on the coming years of fighting for redress. So, the Japanese American National Bowling Assn. was formed, and the first JANBA tournament was held in 1975 in San Jose, Calif.

JA bowling has continued under the JANBA banner since, with national tournaments moving from city to city — all in the West, Northwest or Hawaii, even though historically there have been JA bowlers in the Midwest, East Coast and even Texas, more as a social activity than an organized league sport. Competitive bowlers from the East competed in JACL or JANBA tournaments in Denver, Salt Lake, Las Vegas, Portland, Seattle, up and down California and in Hawaii.

Bowlers fill the lanes at the Nov. 29 Nisei Bowling Tournament at Holiday Lanes.

That’s still the case. This year’s JANBA tournament was held in Las Vegas, and it will be in Sacramento in 2026, then back to Denver in 2027. The tournament still operates under the racial requirements that forced JACL to start its post-war opposition to the American Bowling Congress’s exclusion 80 years ago. JANBA remains an organization “for members (and spouses) of Japanese descent.”

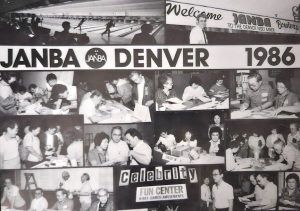

1986 JANBA Denver bowling photos.

That requirement isn’t a problem in Southern California, where so many JAs still live. Every city in the L.A. area has its own leagues. The SoCal Nikkei Bowling Assn. represents bowlers from the San Gabriel Valley to Gardena and all around the L.A. area. The Northern California Nikkei Bowling Assn. is the umbrella organization for leagues from Sacramento south to Gilroy and Stockton and San Francisco and San Jose.

In some areas, there has been a crisis for JA bowling. At one point, bowling became tagged with a reputation as an activity for elders, and membership in local leagues dropped as older bowlers joined senior leagues or, sadly, passed on.

But thanks to younger bowlers, that trend has been changing, with more youth — including younger members of JACL — picking up the ball for heritage and history.

“For a while, I thought it was a dying sport,” says Mae, who at one time was a leader in the Nisei bowling community in the Northwest (she preferred her last name not be used). “You know, after those early bowlers passed on, the younger kids were really not into it. But now, it seems like here in Portland and up and down the west to the San Jose area, there has been a resurgence of young kids bowling.”

One major reason Mae thinks bowling is making a comeback is that “bowling is for everybody. Basketball wasn’t for everybody.” There have been Nisei leagues for basketball and baseball, and golf is a common passion for many JAs, but she thinks golf attracts a different crowd, while bowling is truly open for everybody.

In large part, and in common with others who were interviewed for this story, the special attraction for bowling is the sense of cultural community. “It’s just for the social aspect, the camaraderie, being with friends,” she added. “Scoring was important, yes, but for me, it was always more about the friendships.

A 2024 Holiday Lanes Nisei League potluck

“And it’s still the same to a degree,” Mae continued. “I go to Las Vegas with my sons to watch them bowl. People think I’m nuts going to Las Vegas not to gamble, but to watch the family bowl instead. They can’t believe that I would do that. How can you sit in a bowling alley for six hours at a time? Well, I see a friend from Seattle. I see someone from San Jose I know. So, half the time, I may not end up watching my son bowl, but I’m socializing.”

Mae is excited to see what the next generation of bowlers bring to the sport. “The younger kids now are also trying to encourage more of their friends into bowling,” she said. “And these may not be all 100 percent Nihonjin, but you know, they may be mixed blood or whatever, but they have the appreciation. They have encouraged a lot of their friends to come in, and that’s one of the reasons why this league in Portland is able to sustain itself.”

Bruce Sunada proudly wears his 2025 JANBA shirt

Dominique Mashburn, who is a board member of the SELANOCO chapter and vp of membership for JACL, is one of that younger generation of JA bowlers keeping the sport alive in the L.A. area.

“I think I had a very large fascination with bowling, just because it was an adaptive physical activity for my older brother, who has autism,” she said. But Mashburn was introduced to bowling when she was younger, like many JAs, who go to alleys with their parents and family members and absorb the sights and sounds of the high-fives and the thundering pins.

She agrees that Southern California is a pocket of enthusiasm for JA bowling, partly because of the Nikkei student unions that use bowling as an icebreaker. “So, it has been really great for JACL and SELANOCO to have those university relationships where we were able to build new bridges with them,” she noted.

And Mashburn concurs with Mae’s point that everyone can bowl. “I think that’s the really best part of it because not all sports can do that. It’s the sport that anybody can do. And there’s no judgment. I feel like it’s a really judge-free zone. No one’s a loser; everyone’s a winner. I love it.”

Lincoln Hirata, a 19-year-old college student who’s a leader in JACL’s National Youth/Student Council, is another bowler who represents the future of the sport.

“I think that there is kind of a divide, though,” he observed, “between those who are in JACL and then those who are bowlers and those who are JA golfers. People are either focused on their bowling or their golf, versus, you know, people who are only focused on JACL, right?” (Others like Mae think that bowlers and golfers can coexist, and so do some younger bowlers who hit the links as well as the lanes.)

Hirata, who is from Portland but attends the University of Oregon in Eugene, says many of his generation’s introduction to bowling came from parents or their grandparents, who were part of the community and very involved in JACL or, in his case, also “because I’m very big in my church, you know, the temple. But as time has gone on, it seems that people have just naturally drifted away from the more traditional things and have moved on toward other activities.”

Ironically, one activity cited by some of the older generation of bowlers is having kids. Many parents gave up bowling when they had children and only returned to the game after their kids grew older. Now, they’re bringing their sons and daughters to the lanes. Hirata understands that experience. “My parents both stopped bowling when I was born, and I think that was a trend with a lot of these other families.”

Hirata cites Covid as a prompt for a return to bowling. At first, JAs in his community started golfing because that was a safer outdoor activity. “After that, kids my age, or kids a little bit older than me, started to bowl, and we had this giant influx of young bowlers, you know, 20s, 30s, teens. It’s not like it was everywhere, but when I go to JANBA, I do see a lot of kids my age now.”

Robert Wada, who is vp of the Denver Nisei Bowling League, was raised around bowling. Wada’s mother and her brother were active in the early 1950s JA bowling scene, and she won the singles title at the JACL tournament in 1952. “She was the real bowler in our family,” he recalled. “And that’s kind of how I got roots in bowling.” His uncle later served on the JANBA board for years, and Wada now serves on the JANBA board today. “It’s kind of ironic that eventually I got on the board as well, and now, I’m the old guy in the Denver league (he’s not that old).

Back then, as today, there were leagues or associations all over Southern California. Denver has a significant JA population, but not a big one like around LA. In fact, its bowling community has diminished over the decades, even though it will be hosting JANBA’s tournament in 2027.

Chris Yoshida, president of Denver Nisei Mixed League bowls at Holiday Lanes in Lakewood, Colo.

Chris Yoshida, a Denver native who is president of the city’s Nisei bowling group, organizes games every Tuesday in a Denver suburb. He began his bowling life as a boy. “I started learning how to score for teams,” he recalled. “They used to pay us $1 a game to keep score. So, that’s where I got into bowling.”

Like others, Yoshida appreciates the welcoming nature of bowling. “It doesn’t matter if you’re a good or a bad bowler. They just want to be able to bowl, or they want to be involved in that atmosphere,” he said. “I’m hoping we can get a lot of kids involved in bowling, and then hopefully, we can make sure that the league does not die out. I personally want to keep the tradition alive. I don’t want it to die on my watch.”

A community might live on, but bowling alleys can die out. Many have come and gone over the years, and one of the most notable longtime landmarks of JA bowling in L.A. was the Holiday Bowl on Crenshaw Boulevard. It was opened in 1958 and closed in 2000, and John Saito Jr., a former editor for the Rafu Shimpo and former Pacific Citizen editorial board chair, holds the distinction of being the last JA league bowler to grace its lanes. He even has a pin from that night as a prized artifact on his shelf.

Saito says the Holiday Bowl was a reflection of the status of JA bowling when it was built. “It was started by these four Nisei guys who were real entrepreneurial,” he said. “This was in the late ’50s, when bowling was huge.” The Holiday Bowl became a cross-cultural center of bowling, entertainment and dining for decades. Although the building was a landmark, it had undergone ownership changes and hadn’t been kept up by the time it closed. But Holiday Bowl is often mentioned in accounts of the glory days of JA bowling.

Japanese Americans have long-embraced bowling as a sport that also brings with it camaraderie and cultural traditions. Here, a photo from the Nov. 28 Denver Nisei Tournament at Holiday Lanes.

Bowling alleys may have gone over time, but today, young and old bowlers are keeping the sport alive. And some JA leagues have a built-in source of players. Bing Lau is the administrative director of the San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center, and he has a pool of elder JAs who can be recruited to bowl. He came to JA bowling as the president of the Asian American fraternity at USC, whose brothers urged him to join them in JA bowling.

His day job benefits from his involvement in bowling, Lau says. “Yeah, it’s so important just for people, and I always talk about this from the senior perspective, to get out, to be able to engage with others and give them that activity,” he said. “It’s so good for them mentally to fight loneliness and whatnot, so we actually have a senior league that is attached to our center as well, through our Meiji Club. A lot of the people that used to bowl on Fridays that can no longer bowl, or they don’t want to drive at night, now bowl on Tuesday mornings in our Senior League.”

The sport even led to his marriage. “I met my wife, Eileen, through the league,” Lau said. “She wasn’t a bowler, but I bowled with her cousin, and she came around to watch her cousin. So, we met through the league. We got married on a Friday in Little Tokyo, we had a small wedding and dinner, and then we went bowling that night. We had a cake at the bowling alley.”

Now, that’s dedication to Japanese American bowling.