Pictured at the 2025 JACL National Convention (from left) are Brian Shimomura, Floyd Shimomura, EDC Gov. Paul Uyehara and National President Larry Oda. (Photos: Courtesy of Brian and Floyd Shimomura)

A summer road trip opens up one family’s past

and connects them to the broader JA experience.

By Floyd and Brian Shimomura

From the Editor:

In July, Brian and Floyd Shimomura set out on a road trip from their homes in Northern California to attend the JACL National Convention in Albuquerque, N.M. Along the way to the “Land of Enchantment,” they made a stop at the Amache National Historic Site in Colorado, where members of their family were forcibly incarcerated during World War II. Following, according to Brian Shimomura, is “an attempt to record a small subset of the conversations that I had with my dad, Floyd Shimomura, over the years and help clarify some history related to the redress movement. In this article, we visited Amache to pay respect to our relatives and other Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII. Thank you to Allison Haramoto and Susan Yokoyama at the Pacific Citizen for working with us to publish this article.”

Rediscovering History

Brian Shimomura: Growing up, I knew my dad as the calm, thoughtful guy who made semihealthy Sunday dinners and helped me with homework. I didn’t realize he was the first Sansei national president of the Japanese American Citizens League in 1982, or that he helped advance the redress campaign that resulted in President Ronald Reagan signing a bill in 1988 granting an apology and $20,000 to each person unjustly incarcerated during World War II. We didn’t talk much about our family’s internment history. I was more focused on becoming the best tennis player in Woodland, Calif.

Floyd Shimomura at Amache

Floyd Shimomura: When Brian suggested a road trip to Amache before attending the 2025 JACL National Convention, I was delighted. It was a chance to revisit our family’s past and share stories I hadn’t told him before.

From Denver to Amache

Brian: We flew into Denver and drove southeast toward Amache, the incarceration camp where my grandparents were held. On the way, we talked about the “Lost Japanese Community of Winters” exhibit and my great-grandparents, Itaro and Sawano Shimomura.

Floyd: I helped curate that exhibit in 2021 for the Winters Museum. Itaro emigrated from Wakayama in 1906 and became a foreman on an apricot and almond farm. He married Sawano, also from Wakayama, in 1915.

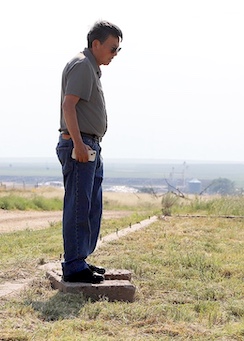

Floyd Shimomura shows a ranger the location of his parents while they were at Amache.

Brian: My dad prepared a binder full of information. On May 15, 1942, Civilian Exclusion Order No. 78 forced all Japanese Americans out of Yolo County. My grandfather, Ben Shimomura, was the designated “responsible” family member.

Brian Shimomura’s grandfather, Ben Shimomura, at Amache, where he was incarcerated during World War II.

He reported to the Civil Control Station in Woodland and received family number 30980. The Shimomura family — Ben, his sister, Harumi, and their parents, Itaro and Sawano — departed from the Woodland Train Station. They were first sent to the Merced Assembly Center, where they slept in horse stalls for three months, then transported to Amache by train with the shades drawn.

Floyd: Ironically, my father said the train served regular meals in the dining car — the best food they’d had since being uprooted.

Amache National Historic Site

Brian: Visiting Amache was surreal. Behind us stood a guard tower, a stark reminder of the 120,000 Japanese Americans imprisoned during WWII. My dad said that this was where my grandparents, Ben Shimomura and Lois Morimoto, met.

Brian Shimomura (left) and Floyd Shimomura visit Amache during their summer road trip to the JACL National Convention in Albuquerque, N.M.

Ben worked in the motor pool, maintaining trucks and making deliveries. Lois, the youngest of six siblings from Cortez, Calif., worked in the dispatch office. They married in Denver in March 1945. Their love story began behind barbed wire, under armed watch, in a country that promised liberty and justice for all.

A ranger shows Floyd Shimomura the location of his parents’ barracks.

Floyd: They were among the fortunate few who returned to Winters. Of the 300 Japanese Americans who lived in Winters before the war, only about 15 percent returned. Many were too afraid. During V-J Day celebrations, Winters’ Japantown was burned down. Signs at the city limits read, “No More Japs!” But the Tufts family, our prewar neighbors, defied public sentiment and invited us to work on their farm.

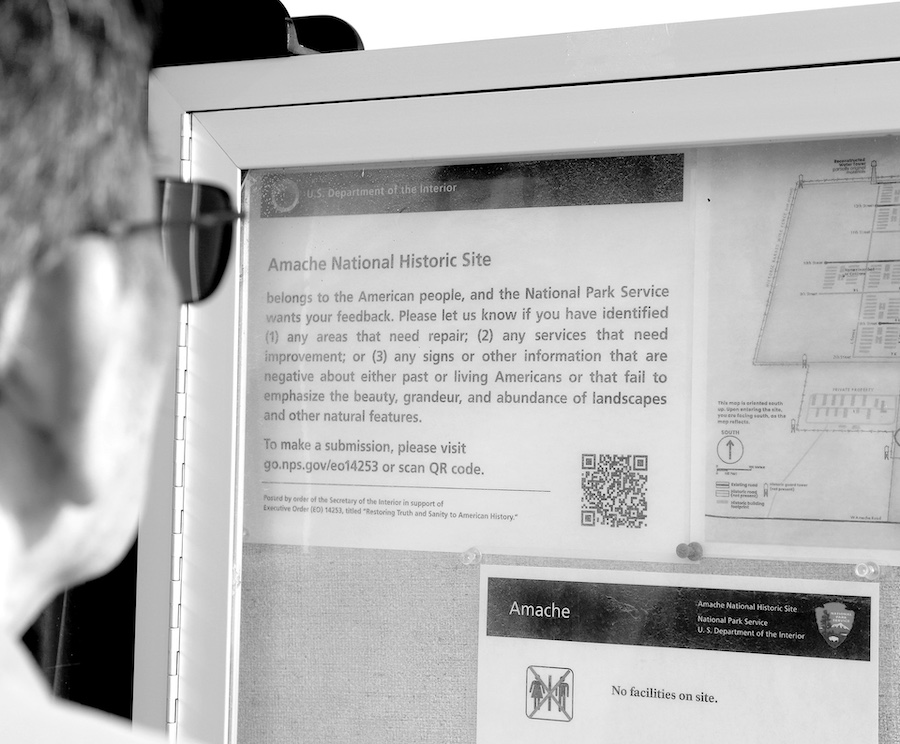

Floyd Shimomura views new signage from the U.S. Department of the Interior at Amache.

Brian: Before leaving Amache, we checked the park bulletin board. A notice similar to one seen at Manzanar asked visitors to report “any signs or other information that are negative about either past or living Americans.”

A ranger and Floyd Shimomura at the site of the Shimomura barracks

We were worried that this might signal a revisionist view of history. Dad had taken me to the JANM dinner where it had declared it would “Scrub Nothing.”

Floyd Shimomura stands on the foundation of a barrack at Amache

On to Albuquerque

Brian: It’s a six-hour drive from Amache to Albuquerque. I asked my dad about his JACL experience and how he became the first Sansei national president in 1982.

Floyd: I explained there were four key factors: I had just completed two terms as national vp for public affairs; I was a law professor at UC Davis specializing in federal administrative law, including monetary claims against the government; I came from Northern California, the largest JACL district with the most votes; and the organization wanted to present a younger face to the community.

I explained to Brian that most Nisei supported “Go for Broke” in WWII, while most Sansei supported, “Hell no, we won’t go” in the Vietnam War. So, many Sansei questioned if the JACL — a mostly Nisei organization — had the ability to truly confront the government on redress.

Brian: I asked about the redress campaign and the 1983 meeting with Japanese Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone.

Floyd: Many, like John Tateishi and Ron Ikejiri, did more than me. But I testified before Congress and wrote briefs for the redress commission. Thanks to Frank Sato, I met with President Reagan’s chief domestic policy adviser, Jack Svahn, in the West Wing. In Tokyo, Ron Wakabayashi and I met Prime Minister Nakasone about trade friction.

Many Nisei board members advised against discussing redress, but Nakasone unexpectedly brought it up. He said Reagan would soon address the Japanese Diet and stay at his residence. Nakasone asked if there was anything I wanted him to say to Reagan.

I said, “Ask him to sign the redress bills.” He nodded slightly and made a noncommittal grunt. I wasn’t sure if he followed through — until 10 years after Reagan left office, when a history professor uncovered documents showing that Nakasone’s administration had quietly lobbied Reagan to sign the bill because he wanted to put it in Japanese textbooks.

The JACL National Convention

Floyd: We arrived in Albuquerque at the JACL National Convention and attended a plenary session on repealing the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 — the law used to detain Issei leaders after Pearl Harbor without due process. One of the detention camps was in nearby Santa Fe. The Trump administration had recently invoked it to detain suspected illegal aliens, even though there was no war. Coming straight from Amache, it made us question whether the lessons of history had truly been learned.

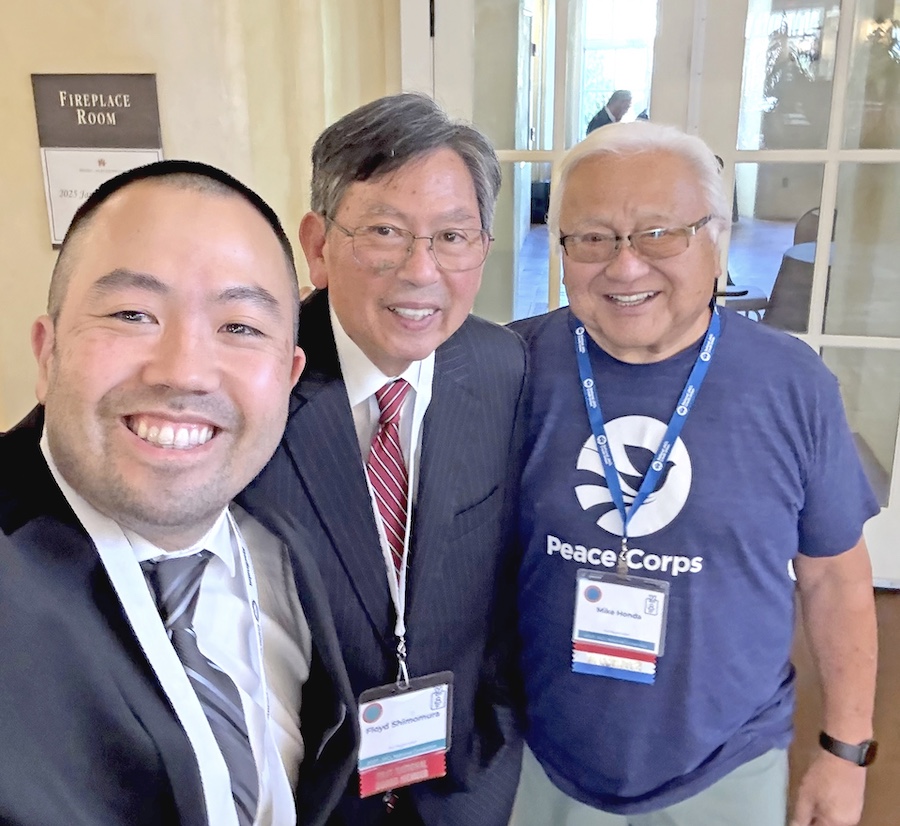

Brian Shimomura, Floyd Shimomura and Mike Honda (right) meet at the 2025 JACL National Convention.

Brian: We also saw a video about Nobuko Miyamoto, a performer and activist who used her art to fight for civil rights and protest the Vietnam War. She performed live at the Sayonara Banquet the next evening.

Coming Home

Brian: Since getting married in 2021, my wife, Alissa Shimomura, and I have traveled to 22 countries to photograph the world. We hiked the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu, climbed Mount Fuji, rode camels at the Pyramids of Giza, endured 115-degree heat at the Taj Mahal, caught Covid in Bali and swam below an active volcano in Iceland. But this road trip — with my dad, to an incarceration camp and a JACL national convention — was one of the most meaningful experiences of my life, second only to getting married.

Floyd: As a dad, it was gratifying to see Brian connect with our family’s history and the broader Japanese American experience. It was also a little sad. The road trip reminded me that the fight for justice is never truly over — and that passing on these stories is part of that fight.

Brian Shimomura (left) and Floyd Shimomura at the 2025 JACL National Convention

Floyd Shimomura is a past JACL national president. Brian Shimomura is a past board member of San Francisco JACL and a current manager for the State of California. They reside in Woodland, Calif., and Daly City, Calif., respectively.