On July 6, my husband and I traveled to Twin Falls, Idaho, to attend the 15th Annual Minidoka Pilgrimage. I was asked to be the opening keynote speaker. Initially, I wondered why they would ask the mother of a transgender son, whose family was not imprisoned in Minidoka, to open up the pilgrimage. But as I spoke to one of the organizers, I realized that so much of what I went through when my child came out first as lesbian and then transgender ran parallel to the feelings that our Issei and Nisei may have felt.

My strongest feelings were fear, shame and sadness, and as I listened to stories about Minidoka, I could feel those same feelings coming through in their stories.

Individuals felt fear when they were herded into animal stalls, bussed to desolate, dusty land and treated like the enemy even though they were American citizens. There was no trial, no verdict, no sentencing. All were sentenced to be imprisoned because of their ethnicity and where they lived.

Families lost everything they had worked hard for because while they were in camp, their homes were foreclosed on and belongings taken. There was so much fear for their future, the safety of their family and the prejudice they faced. I could relate to it all.

I also heard about children grieving over having to leave their pets behind because they could not be taken with them. I have a dog named Mochi that I love and Aiden’s dog, Kuma, who is like my furry grandchild. I would have been devastated to leave them behind, not knowing how they would survive and knowing they wouldn’t understand why we abandoned them.

I heard stories of children taking in a bird, snake or even a centipede as a pet at camp to fill the void and sadness of leaving their own pets behind. Those are stories I did not know before I came to Minidoka.

And then there was the shame and humiliation of camp. Many came to camp before it was even made livable. There were barracks that were so poorly constructed that the dust came through the cracks in the walls. The barracks did not have privacy, so sometimes only a sheet separated living spaces.

One woman talked about toilets made of a plank of wood with holes cut in them, and someone else mentioned chamber pots (a pot used as a toilet), which were in the barracks, so at night when it was freezing, they didn’t have to trudge over to the communal bathrooms.

There were so many stories.

And yet in the stories, there were woven also moments of pride, hope and perseverance.

One woman shared she wasn’t proud being a Japanese American, and then she went to camp. She left camp proud. She didn’t describe what made her proud, but from the stories that I heard, there was much to be proud about.

The ways the Issei parents kept their families together. The ways mothers persevered without complaint (gaman) and the ways they shielded their children from the horrors and humiliation as best they could. A lady I met named Lilly called her mother her heroine because of the way she handled going to camp and making it the best experience possible for the kids.

Some of the young children who are now in their late 70s and 80s talked about being fed candy and being told that they were going on a vacation and having fun. I can only imagine how much courage and love it took for these Issei and Nisei to create this experience for their children, so that when they grew up, they did not lose their entire childhood years to fear, shame and sadness themselves.

I also heard stories of neighbors taking care of homes and belongings, so that when families returned home, they had not lost everything. This actually happened to my family.

My father’s family home was taken care of by neighbor. The Haggars rented out the home, collected the rent and paid the bills, so Grandpa and Grandma Ogino did not lose their home like so many other Japanese. How lucky my grandparents were to have people who cared and showed up for them.

The reason I go around the country to speak about being the mother of a transgender son is to raise awareness about transgender issues. I want to thank Lois from Southern California for telling me she learned so much from my keynote. It inspires me to keep speaking and sharing my story.

I also speak because I know that if I talk about my shame, sadness and fear, it helps me to heal and move on from those moments. It is not always easy, but I believe it is necessary for me to live a life of joy, gratitude and hope.

At Minidoka, I saw the same things happening to those participating. There were tears, there was pain, yet there was also so much gratitude and hope in the air.

One woman, who I fell in love with, was from Detroit, and her name was Catherine. She was on a panel of women who talked about their camp experiences. Catherine is in her 90s, and she said, “I am at the end of my life, but I am grateful for this life, and I thank you for being part of it.” Here was a woman that was living to her last days with joy and appreciation.

Minidoka pilgrimages honor those Issei and Nisei who lived through this experience, raises awareness of these concentration camps and hopefully brings out the courage in all of us, so that this kind of discrimination will never happen again.

As Anna Tamura, the closing speaker at the pilgrimage so beautifully stated, “My hope is that you will draw inspiration from Minidoka … to be brave helpers that rise to the occasion and stand up and support individuals and communities who are being victimized like our Nikkei community was 75 years ago, here at Minidoka.”

I hope when I am gone, people will say I was a brave helper to both the Nikkei and LGBTQ communities. And whether you do something quietly or something out loud, I hope they will say that about you, too.

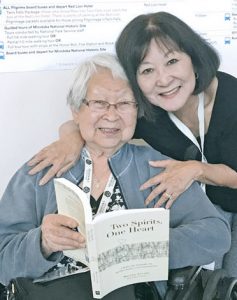

Marsha Aizumi is an advocate in the LGBT community and the author of “Two Spirits, One Heart: A Mother, Her Transgender Son and Their Journey to Love and Acceptance.”