JACL Philadelphia board members Don Kajioka, far left, and Rob Buscher, right center, and Hiro Nishikawa, second from right, with Muslim American leaders at a solidarity picnic, held at Al Aqsa Mosque, which was vandalized in late 2015 by an act of anti-Muslim bigotry.

By Rob Buscher, Member, JACL Philadelphia Board of Directors

(Originally published in the Dec. 16, 2016-Jan. 26, 2017 Holiday Issue of Pacific Citizen.)

Just over 50 years ago amidst the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the New York Times Magazine published perhaps the single most important article about the Japanese American community to date.

What seemed at the time to be an innocuous editorial piece about the successes of the JA community, the article dubbed us (and all AAPIs by extension) as the “Model Minority.” Titled “Success Story, Japanese-American Style,” this eight-page article, written by William Pettersen, made the case that despite many hardships, JAs had pulled themselves up by their bootstraps and established a stable and successful community without any outside assistance.

This was dangerous for two reasons: It implied that JAs (and all AAPIs by association) are insular communities that thrive in isolation and do not require government support or other intervention, and it deliberately drove a divisive wedge between our community and other communities of color.

The premise of this article was that because Japanese Americans accepted the mass incarceration without complaint, we showed a certain “moral character” and “work ethic” that allowed us to succeed where other “problem minorities” had failed. But this was only part of the story.

No, our community did not passively nor quietly accept this situation; we bided our time and planned for the future. An entire generation of young men paid a blood-tax, enlisting to serve in the same military that kept their families behind barbed-wire fences. There were also plenty of dissenters who refused to sign the loyalty questionnaire – and the No-No Boys who outright resisted camp administration. Our elders were revolutionaries whose very existences were acts of resistance.

For most of our history, AAPIs have struggled to find their place in a society that sees race and ethnicity as a black-white binary. A few stories come to mind that perfectly encapsulate this experience.

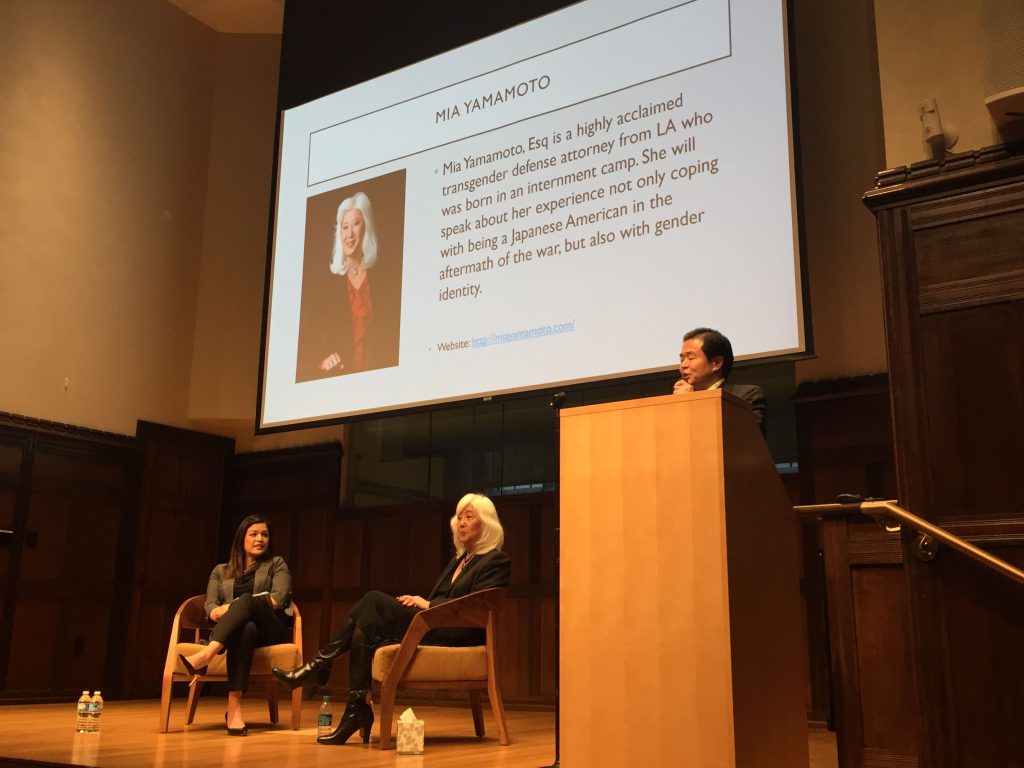

From left: NBC10 news anchor Denise Nakano, Mia Yamamoto and JACL Philadelphia President Scott Nakamura discuss transequality at an event sponsored by the JACL’s Philadelphia Chapter.

I’ve been told by several JA elders who did voter registration work in the segregated Jim Crow South about the first time they had to choose between using the white or colored bathroom, drinking fountain or bus section. Mostly everyone I spoke to told me they picked colored when given the choice, since it was clear that they were not white. However, one woman remembering her first time on a segregated bus told me she must have seemed so visibly perplexed that an African-American woman took her by the arm and sat her in the middle.

In many ways, our community is in the middle. We enjoy relative privilege as a so-called “Model Minority.” We are not being actively profiled by law enforcement in the same ways that members of the African-American, Latino or Middle Eastern communities are.

Derisively referred to as the “honorary whites” by some, we are perceived as a nonthreatening standard to which all other minority groups should be held. It should come as no surprise that many would choose to buy into this idea, especially as newer waves of Asian immigrants struggle to find their place in this country. It is easier to be associated with whiteness than blackness in a society that upholds white supremacy and anti-blackness.

But our community is still at-risk in many ways. We live in a social climate where it has become acceptable to incorporate hate speech as political rhetoric, and white nationalists have been given a legitimate platform in our nation’s highest office.

It seems like references to the JA incarceration have become more frequent and positive in tone, cited as a precedent for possible future Muslim bans or deportations. One does not have to search hard to find the latent racism toward Japanese and Japanese Americans on Dec. 7 and other auspicious WWII anniversary dates throughout the year. In the visitor books at Manzanar and elsewhere, messages supporting the camps have been written recently by individuals who agree with E.O. 9066.

I suppose it should not shock us either that during the recent tsunami scare in Japan, the comment section on Fox News’ live feed was filled with remarks such as: “Deport Japan,” “if we can nuke to destroy there [sic] population least nature will do humans nuke job 🙂 more deaths the better when it comes to Asians there [sic] lives are as worthless as a cockroach,” “GOD BLESS HIROSHIMA BOMBINGS” and “i hope you japs die.”

But what would it take for the Internet ravings of white nationalists to materialize as actual violence? Just over 30 years ago as the media blamed Japanese auto imports for American factory closures, Vincent Chin was killed by Detroit autoworkers who thought he was Japanese.

As economic and political tensions rise between the U.S. and China, it is not unfathomable to imagine a situation where East Asians could again be targeted in the near future.

We are at a point now as a nation, but also as a community, where it has become necessary to choose whether we fight on the right side of history or idly abide by the status quo of oppression.

This rift in our country will not be solved by people signing Internet petitions or wearing safety pins — only by deliberate and direct action aligning our community with all people of color and other historically underrepresented communities.

It is time to go back to grassroots activism and form broad-based coalitions that express solidarity with other marginalized peoples. I argue that we as AAPIs are best suited for this challenge.

We took AAPI, an umbrella term created as a matter of bureaucratic convenience, and transformed it into a full-fledged, cultural-political union through the Asian American and Pacific Islander Movement. Our demographic encompasses incredible diversity of ethnicity, color, religion, language and culture — yet, for the most part, we are able to relate with one another through our shared experiences of otherness and rally around each other’s causes.

As a microcosm of American society, AAPI community spaces have achieved a level of inclusiveness unparalleled. Let us become a new model for inclusion, solidarity and resistance and lead our communities through this unprecedented time.