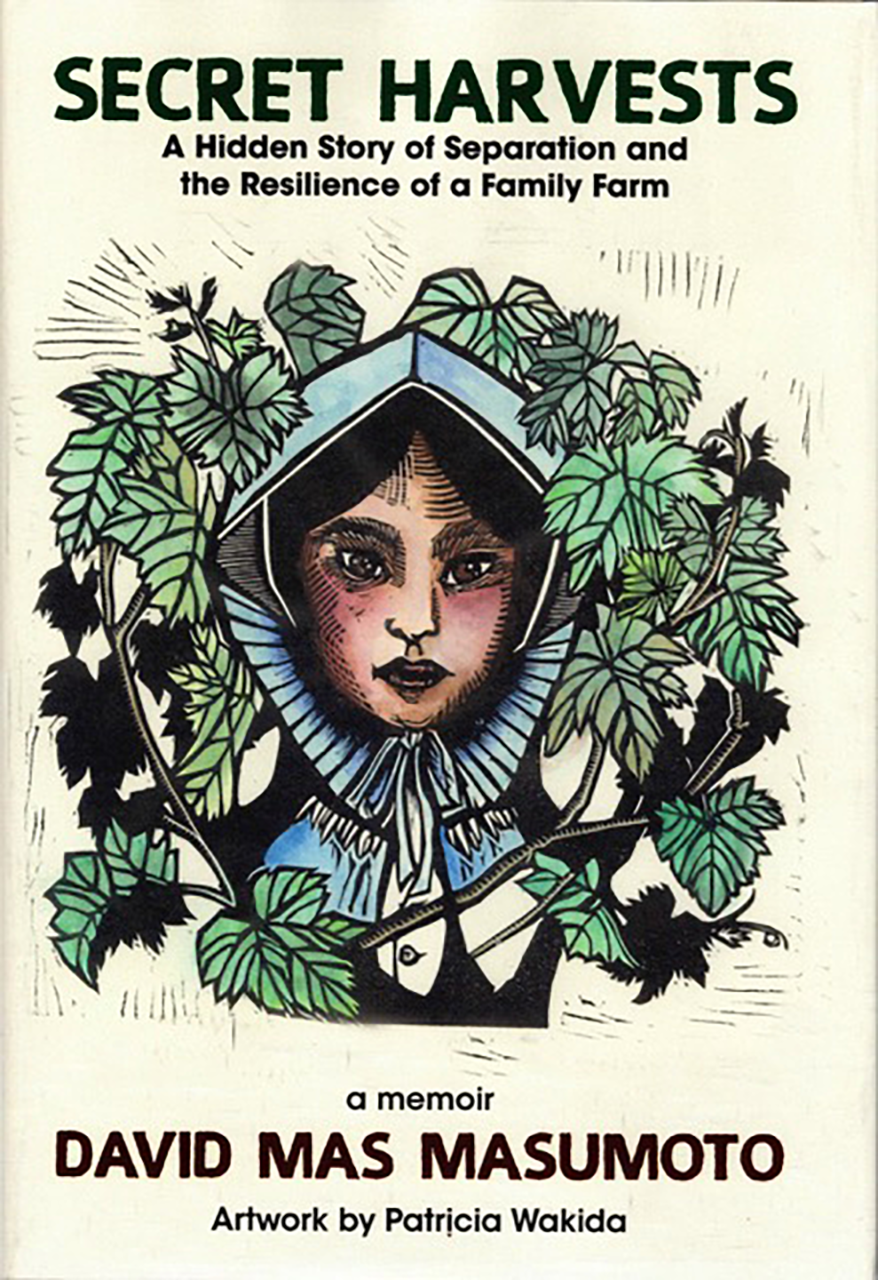

Artist Patricia Wakida created block prints to illustrate

David Mas Masumoto’s Aunt Shizuko for “Secret Harvests.”

The discovery of a long-lost aunt leads to an exploration of stories that reveals family secrets in author/farmer David Mas Masumoto’s ‘Secret Harvests.’

By Alan Oda, Contributor

“Every family has secrets,” says David Mas Masumoto, “secrets that need to be told.”

His latest book, “Secret Harvests,” is about a relative whom he had not previously met, but more significantly, an aunt that was presumed dead many years previously. Masumoto tells of the bewilderment of learning about his long-lost relative, leading to the exploration of stories and tales revealing the secrets of her and her family, surrounding an almost anonymous life. The author, along with artist Patricia Wakida, were featured in a March 18 conversation held at the Tateuchi Democracy Forum, presented by the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, to discuss the new book.

Masumoto is as famous for his authorship as he is for his organic produce, grown on the family farm (masumoto.com) in Fresno, Calif. His award-winning sustainable farming also includes nectarines, apricots and seedless grapes; the family’s famous Sun Crest peaches are described as “one of the last truly remaining juicy peaches.”

Masumoto is as famous for his authorship as he is for his organic produce, grown on the family farm (masumoto.com) in Fresno, Calif. His award-winning sustainable farming also includes nectarines, apricots and seedless grapes; the family’s famous Sun Crest peaches are described as “one of the last truly remaining juicy peaches.”

PBS also broadcast the documentary “Changing Season on the Masumoto Family Farm,” based on the narrative of his family’s agricultural succession. The farm planted its roots in 1948 after Mas’ father, Takashi “Joe” Masumoto, returned to the Central Valley after being forcibly incarcerated in an Arizona concentration camp during World War II. Mas Masumoto attended the University of California, Berkeley, not planning on following in his father’s footsteps. But after studying sociology and then learning about its connection to the ecosystem and the earth, he returned home to embrace and cultivate the family business.

As a writer, he has written 12 books, including the newly published “Secret Harvests.” Masumoto is also a columnist for the Sacramento Bee and the Fresno Bee.

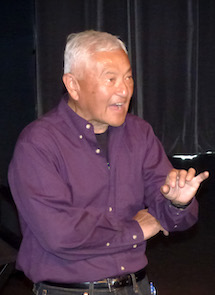

In speaking about how being a farmer helps with his writing and vice-versa, Masumoto embraces each and has found a way to interconnect them both.

“They are intertwined and woven together,” Masumoto said. “Farming allows me the time and solitude to think, reflect and write. Especially with our perennial crops, I have a wonderful dormant winter season with writing during long nights and cold days. It’s perfect for an author to drill deeper into topics. I also write a lot about family and nature and at the same time I can be literally out in the real world of nature daily. … Writing has provided me with a wonderful entry point into the world of growing food.”

Author and farmer David Mas Masumoto addresses the audience at JANM’s Tateuchi Democracy Forum. (Photo: Alan Oda)

Masumoto also explored new ways to work the farm and build upon the multitude of relationships needed to successfully sustain efficient operations while understanding the power of human contact and emotions as part of how to nurture his crops.

“Writing allows time for reflection and a hope to put things in context,” he said. “The true value of food is not based solely on the price you get from a sale. It’s also about the experiences that surround food — in most cases, food is a communal act and embodies family, tradition, community and people. It’s what good writing can do, too. … The art of storytelling has thrust our farm into a different universe, and I’ve been fortunate to build a relationship between words and produce, between our physical labors and the spiritual world of growing life.”

Masumoto’s latest offering, “Secret Harvests,” unearths his own intergenerational family story, peeling back layers to cultivate new light on his own identity and that of his family all while sustaining his connection to his farmland.

He begins by telling of his meeting with his then-94-year-old Aunt Shizuko after a surprise call from a local funeral home. Masumoto learned that his aunt was in its hospice care program, just a few miles away from his family’s farm. Shizuko Sugimoto was mentally disabled due to childhood meningitis and was separated from her family when they realized they could no longer provide the needed care and support for her while they were incarcerated with other Japanese Americans during WWII.

Sugimoto became a “ward” of the State of California, which led to 70 years of moving around state mental institutions — the family completely unaware that she was still alive until her final years.

David Mas Masumoto with his Aunt Shizuko (Photo: Courtesy of David Mas Masumoto)

Masumoto chronicles his Aunt Shizuko’s life, based on documented history and delving into his family archives using “creative nonfiction” storytelling. He tells many stories describing the tragedy, loss and resilience of war-era Japanese Americans, but also documents the dubious history of care for the mentally disabled for this population.

Masumoto’s Aunt Shizuko was his mother’s sister. Born in 1919 to a family of Central Valley farmers, she was afflicted with meningitis at the age of 5. Limited medical care led to her permanent brain damage. “(We) were aliens, we were poor. We had no health treatment. Her brain stopped developing,” said Masumoto.

The family provided for Shizuko through the Great Depression, until the family was relocated to Arizona. A deal was made with local authorities to allow Shizuko to become a “ward of the state.” Masumoto learned that his aunt was then assigned to numerous institutions throughout California, her family having lost contact with her while incarcerated at Gila River.

An additional block print image from “Secret Harvests” (Photo: Alan Oda)

Decades later, after Shizuko had suffered a stroke, the local funeral home did its own research, discovering the obituary of Masumoto’s father, which they used to search for Shizuko’s living relatives. Masumoto said that “they wanted to make sure ‘Miss Sugi,’ the name she was known by, didn’t die alone.”

“Secret Harvests” weaves his family’s travails before, during and after WWII with Shizuko’s story, with Masumoto also piecing together his aunt’s nine-plus-decade journey that culminated with their meeting in 2012.

Describing his use of the aforementioned creative nonfiction storytelling, Masumoto said “when you don’t have [all of] the facts, you have to use a bit of your imagination, your emotions.” There was very little written documentation to work with, “but that was because my grandparents were illiterate. Does that mean their story doesn’t count?”

“So, you can’t make stuff up. It’d be easier if I’d written a novel, but I’m a bad novelist,” Masumoto continued. “That began a journey to discover this mystery … it wasn’t a problem to be solved.”

Masumoto uses the imagery of ghosts to describe his collective upbringing. “Ghosts are the ancestors I live with, I farm with,” he said, with the ghost of Shizuko being the focus of the story. “She experienced generational trauma that I inherited.” Throughout the writing of the book, Masumoto said he kept asking questions — “We live with ghosts that actually want to talk to you.”

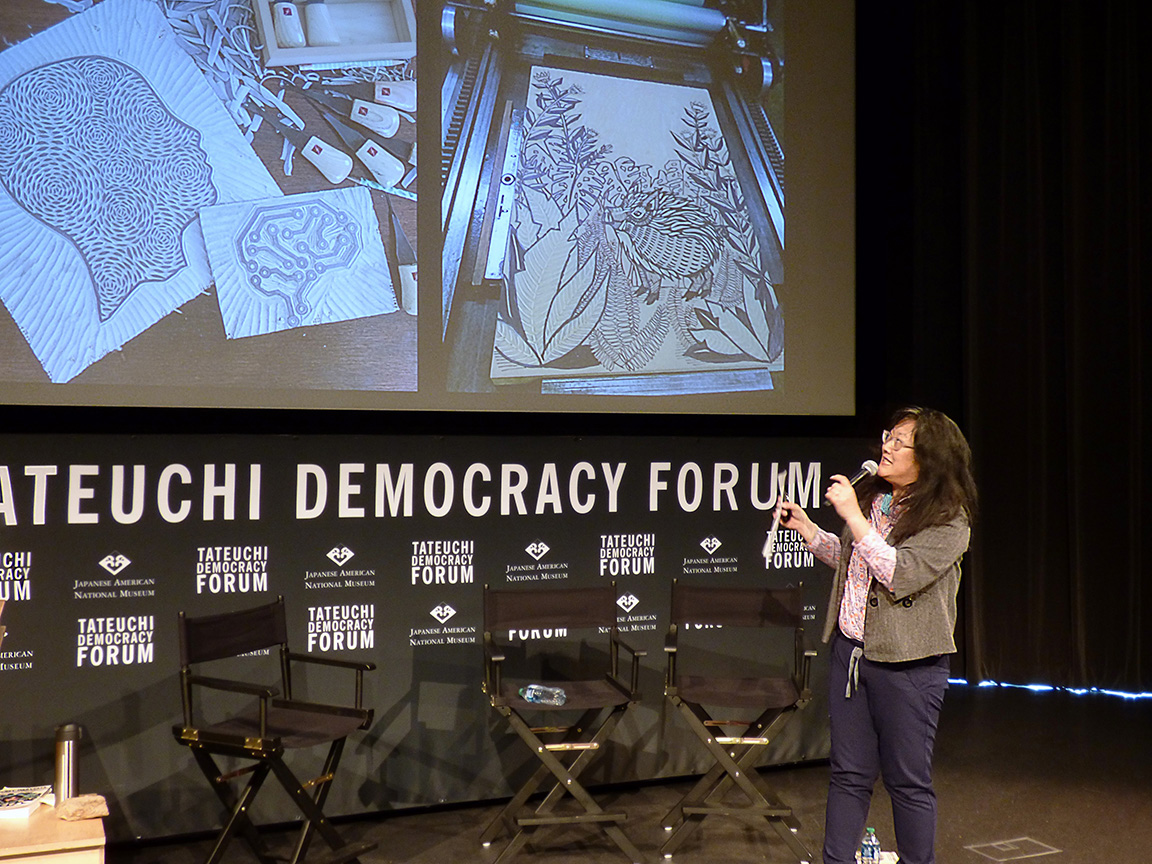

Artist Patricia Wakida talks about one of her 34 block prints that are featured in “Secret Harvests.” (Photo: Alan Oda)

Acclaimed artist Wakida, who joined Masumoto at the JANM book discussion event, was then chosen by Masumoto to illustrate the book. Wakida, a Yonsei (fourth-generation Japanese American) artist, is herself a writer about Japanese American history and culture. She has served as a community developer, working with JANM, the Densho history project, the Oakland Museum of California and the Topaz Museum. Wakida now owns a linoleum block and letterpress business, which involves hand carving and creating unique artistry using her 100-year-old printing equipment (www.wasabipress.com).

“David asked me in 2018 to work on this project. I created 34 (hand-carved) block prints for the book,” said Wakida. She used drawings and photographs for much of her work but noted “some of the chapters weren’t that superobvious” when it came to the artwork, requiring some creativity. “I used my husband and son to pose as models to create some of what eventually became wooden, then linoleum blocks.”

Through her artwork, Wakida said, “I wanted to make Shizuko visible. I wanted to make her wholly, totally vibrant. David gave me full freedom with my work.”

Wakida took particular care in creating the cover image. “There were no photos of Shizuko as an adult. I knew the women of the time dressed in bonnets to keep them from sexual harassment,” she said. “I tried to make Shizuko as beautiful as she could be. I felt it was a way to honor her even though she herself couldn’t tell her story.”

An additional block print image from “Secret Harvests” (Photo: Alan Oda)

“I never gave (Wakida) an idea of what she should do,” said Masumoto. “I sometimes changed my writing based on the imagery she created.” He said the book was a challenging project, noting “it went through 65 drafts. It got better, these projects evolve through the work … we [continually] add to our own stories.”

Masumoto then told of his first meeting with his Aunt Shizuko. “She was comatose (after her stroke) when she arrived at the assisted care center, and they nursed her back to life,” he said, explaining that she awakened from her coma after three months. When he met her, Masumoto said her first words were “where have you been?”

We were strangers, yet “the first thing she did was kick me in the leg because she wanted her shoes tied,” Masumoto recalled. Shizuko was known for “her feistiness, her energy. She loved to go around to the staff and punch them. She had a spirit about her.” He recalled his aunt also “loved hot coffee. She’d then fling her Styrofoam cup over her shoulder against the wall. She wasn’t very Japanese. … Marie Kondo wouldn’t have liked her.

“She wasn’t perfect, but she seemed to love an imperfect life,” said Masumoto. “We share the same spirit with our farm. Beauty is found in the imperfect, the incomplete … life as the impermanent.”

As he wrote the book, Masumoto said, “I was very ignorant about disabilities. [I learned] we are disabled by our society, not our bodies.” Being Japanese made Shizuko’s life even more difficult, stating she was once labeled as “Mongoloid,” an outdated and degrading term once used to describe Down’s Syndrome. “Shizuko wasn’t a failure, there were multiple levels of systemic failures. She strove to live with her disability, she was not a failure,” he said.

Shizuko Sugimoto died in 2013, a year and a half after waking from her coma. “Stories don’t end. Her passing was the beginning of piecing together her story,” said Masumoto. “It brought the family together as I asked questions. It solidified the bonds of family.

I also had to respect some of this was what they wanted to forget. The story continues.

“The Japanese use the term shikata ga nai, ‘it can’t be helped.’ What does this really mean? It’s such a common term used by families. For Shizuko, it was both a blessing and a curse,” said Masumoto, an apt term to describe the life of his aunt.

When asked about what he wants his readers to take away from the book, Masumoto said, “Start asking questions about your own family. Every family has secrets, not all of it is (family) dirt. It’s the power of language. ‘Secrets’ can simply be questions left unasked. It’s not a one-time thing. It’s about sharing.”

“Secret Harvests” is now available via the JANM online store (janmstore.com/collections/books-media) and other popular retailers.

Funding for this article was provided by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL redress strategist Grant Ujifusa.

Artist Patricia Wakida elaborates on the block print tools used to create her artworks. (Photo: Alan Oda)