“Remembrance,” shown behind Bob Matsumoto, is a symbol of the loss of freedom and dignity of the Japanese American community. (Photo: Courtesy of Bob Matsumoto)

The art director on carrying on the legacy of kindness, combating anti-Asian hate and the need for creative thinking.

By Lynda Lin Grigsby, Contributor

Bob Matsumoto is the patron saint of creativity. The advertising art director, whose name and work continues to echo in the minds of industry trendsetters long after his retirement, is famously averse to retreading old ideas. He is always looking for what he calls a “fresh take.”

A former student at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, Calif., where Matsumoto taught for eight years, said in his advertising concept class, she created cool visuals but was often sent back to the drawing board to find the “big idea.”

“Again and again,” said Marian (Monsen) Bell, 70. “I learned to never give up trying to do better.”

“This has happened again,” said Matsumoto about anti-Asian hate. (Photo: Courtesy of Amiko Matsumoto)

Vestiges of the same demand for out-of-the-box thinking revealed itself when Matsumoto, 83, called before our scheduled interview to ask for the idea behind this article. This is not uncommon in the journalism world when jittery subjects (or their gatekeepers) like to get a feel for the kinds of questions going to be asked and perhaps set up a few boundaries, but Matsumoto’s question was sincerely about the idea.

At the Pacific Citizen, articles often circle around variations on the same theme: the shared history and intergenerational impact of the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. It’s a part of Matsumoto’s own narrative as a 4-year-old incarcerated at Manzanar, but it’s a story he has already told to reporters for other media outlets, so once again, he asks, “What is the big idea?”

Bob Matsumoto (front row, left) was only 4 years old when his family was incarcerated at Manzanar. (Photo: Courtesy of Bob Matsumoto)

The idea might be that Matsumoto blazed a trail in advertising during a time when Asian American presence was scarce. A self-described Oakland-born scrapper should not have been able to garner so many career accolades and respect if it weren’t for the kindness of mentors and what Matsumoto says is just pure luck. Tracy Wong, an influential advertising art director of the WongDoody Agency, calls Matsumoto “a legend.”

Every person who ascends to a higher order than his/her birthright can cultivate connections with the higher ranks, but the truly exceptional ones authentically bond with superiors and inferiors — the latter, who like Bell, just want to be a part of his world. It’s a gift that if one is lucky enough to have, can light the way for other talent to achieve success, and Matsumoto has it.

Proof of his exceptionalism can be seen in photos — in a black-and-white one, a young Matsumoto grins joyfully next to Helmut Krone, a pioneer of modern advertising whose Volkswagen Beetle campaigns in the 1960s are timeless.

Krone’s stern demand for perfection made people who worked for him question if he ever relaxed. But in the photo, Krone has an arm casually slung around Matsumoto and the faintest upturn of a smile. It is a portrait of a legend and mentee.

The hint of a smile on famously austere Helmut Krone’s face makes this photo one of Matsumoto’s most-prized possessions. (Photo: Courtesy of Bob Matsumoto)

In other photos over his many years in advertising, Matsumoto smiles just as exuberantly — this time as a mentor — next to former students, who have become successful art directors and creative entrepreneurs still chasing the next big idea.

Paying It Forward

On the day of our first chat over Zoom, he can only afford an hour of time to talk about himself. Matsumoto has been up since 4 a.m. with visuals for his latest project dancing in his head. Some people think in words; Matsumoto thinks with visuals.

He likes to say every creative person needs to keep their minds well-oiled. He is wearing glasses and an impeccably crisp polo shirt like he is ready to flee to the golf course at any moment. While he talks, his email inbox incessantly pings with incoming messages, and his home phone line competes for attention.

Matsumoto is still in demand.

He is the first to admit his life would be radically different if it weren’t for the kindness of higher-ups who invested time and money in him.

In Sacramento, Calif., young Matsumoto landed an apprenticeship in the art department at KCRA-TV, the city’s NBC affiliate where he met Bob Kelly, a legend in broadcasting. For the lucky, meetings like these might result in a promotion or new opportunity. For Matsumoto, the meeting was life changing.

Kelly offered to pay for his entire education at ArtCenter with two stipulations: all the money needed to be paid back interest free over time, and Matsumoto had to promise to help others.

The offer brought tears to George Matsumoto’s eyes. The Nisei farmer grew up with nine siblings working the strawberry fields in Elk Grove, Calif., before losing everything during WWII. It was an opportunity he could not offer his son.

For Matsumoto, the gesture planted a seed of kindness he would spend the rest of his life paying forward.

“What Bob Kelly did for me is ingrained in me,” he said.

While teaching advertising concepts at ArtCenter, Matsumoto learned that his student, Julian Ryder, wanted to become an art director, so on weekends, he worked one-on-one with Ryder to prepare his portfolio.

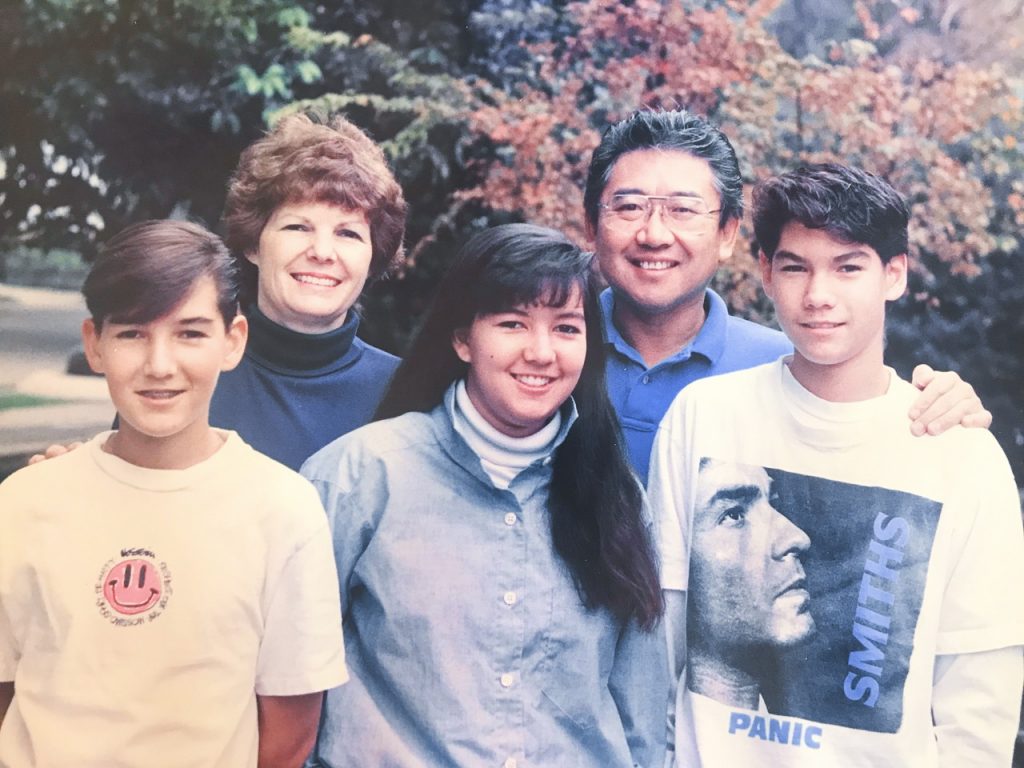

(From left) Michael, Linda, Amiko, Bob and Paul Matsumoto circa 1988. (Photo: Courtesy of Bob Matsumoto)

“I would show up at his house on Saturday mornings, and we’d sit at his kitchen table working on my ads while his wife, Linda, would be giving their new baby a bath in the kitchen sink,” said Ryder, 75, founder and chief creative officer of a creativity education and training firm.

The list of successful creative thinkers to flourish under Matsumoto’s mentorship reads like a who’s who of the advertising industry, including Bell, who credits Matsumoto with helping her land her first advertising agency job. He even took her portfolio from Los Angeles to New York City, where all the top agencies were located.

“How do you thank someone who does all that for you?” said Bell.

Ostensibly retired from advertising and teaching, Matsumoto is pouring his creativity in more personal projects. The latest is a private documentary about Peter Drew, a jazz musician who started composing purely as a hobby because what would a man in his 80s do professionally in the music industry at his age? He drops a nationally acclaimed CD.

On Aug. 10, Matsumoto will begin shooting the documentary — remotely. With the pandemic still raging, he prefers not to be at airports or sitting shoulder-to-shoulder with other passengers. Who could blame him? Technology offers him the ability to be there virtually.

He hired a videographer to position him onscreen exactly where he would stand if he were there in person.

“I mean this is normal when you’re in the business,” he said.

Junior mad man

Advertising in the 1960s was the era of the creative revolution, a golden age famously depicted in the AMC TV series “Mad Men.” During this time, lengthy text gave way to big ideas, snappy headlines (a precursor to clickbait) and pictures.

Matsumoto went into advertising after graduating from ArtCenter because it was where ideas affected culture.

There was no other agency where conceptual thinking was more important than at Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB). In the advertising world, Bill Bernbach is iconic for shifting the focus from formulaic advertising to new ideas.

Matsumoto entered DDB on the ground floor. He landed in New York and called the ad agency from an airport telephone. During his earliest days at the agency, he made $65 a week and slept on a cot in a friend’s closet.

It didn’t matter. He was a junior mad man, a nickname derived from New York’s Madison Avenue, where all the major advertising agencies were concentrated.

Matsumoto was the first Japanese American at DDB, perhaps the second Asian American, and one of just a handful working in the industry.

At DDB, creativity was king. The agency stressed conceptual thinking: the combination of creative imagery and thought to trigger deep emotional responses.

“Conceptual thinking is what wins Oscars for writers and directors and Gold Lions for brilliant television advertising,” said Ryder, a former creative director for ad agencies in Los Angeles and New York.

Matsumoto won a Gold Medal Award from the New York Advertising Art Director’s Club for this 1970 Volkswagen ad. (Photo: Courtesy of Bob Matsumoto)

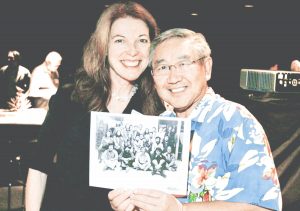

The principles Marian Monsen Bell learned from Matsumoto in his advertising concept class prepared her for a lifetime of creative problem-solving in advertising and in life. Bell is pictured here at a 2009 ArtCenter event holding a class photo. (Photo: Courtesy of Marian Monsen Bell)

His 1969 commercial “The Egg” is a close-up of an egg cooking while voices talk in the background on the telephone. It’s simple and distressing at the same time to watch the egg burn while a conversation carries on. The commercial is part of the Museum of Modern Art’s Permanent Collection.

Matsumoto later became VP and creative director of Della Femina Travisano and started his own agency, but Bernbach’s words stuck with him.

Standing in a roomful of mad men, Bernbach said, “You know, you creative people have all this talent. Don’t keep it here at the agency. Go out and make a difference.’”

In his retirement, Matsumoto is doing his most important work.

He’s leaving a legacy by channeling his creativity toward people, not products.

An Existential Cry for Asian Americans

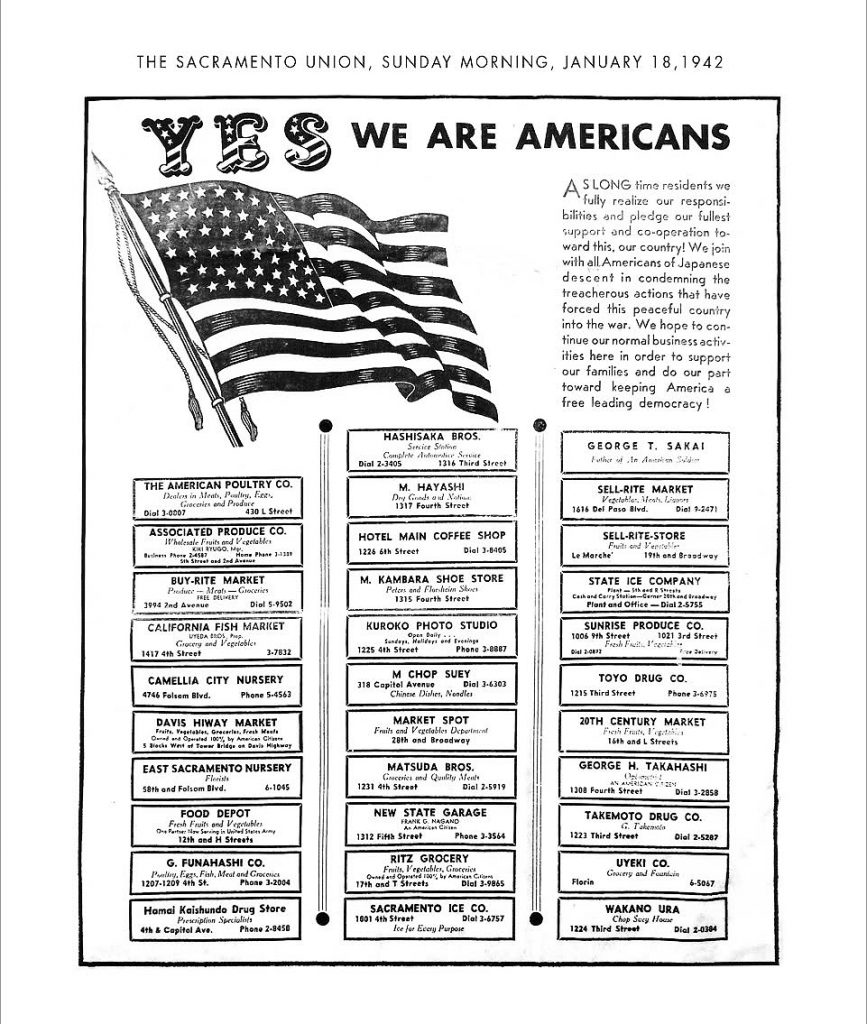

The “original” Matsumoto ad was a collective of Japanese American business owners asking the community to recognize their humanity. (Photo: Courtesy of Bob Matsumoto)

There is an ad that hangs in Amiko Matsumoto’s house that has personal meaning to the family. After Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, George Matsumoto and other Japanese American business owners bought an ad in the Jan. 18, 1942, issue of the Sacramento Union to proclaim, “Yes, we are Americans.”

It is an existential cry of a petrified Japanese American community begging their country to recognize their humanity.

“The ad reminds me of their patriotism and dedication to our country, of what can be lost when we, as a country, are not vigilant to live up to the ideals upon which the nation was founded, and how important it is that we learn from history and remain committed to fighting for justice for all,” said Amiko Matsumoto, 50, a Washington, D.C., JACL member and Bob Matsumoto’s daughter.

Matsumoto thinks about the “Yes, we are Americans” ad often.

In 2018, it inspired him to design “Remembrance,” a poster with three simple elements — three lines of barbed wire in red, white and blue set to a black background to symbolize the darkest days of American history. Matsumoto has also licensed the design for merchandising on T-shirts, hats and mugs. The poster hangs in the offices of lawmakers and on walls of JACLers.

For Matsumoto, “Remembrance” is a symbol of loss and a reminder of his love of country with all its imperfections. In front of his Burbank, Calif., home, an American flag flaps in the wind. In his living room hangs a picture of an American flag made from baseballs and bats.

“Until you lose everything, or you live in a different country, that’s when you realize, yes, we are lucky to be Americans,” he said.

The Matsumoto family attended a 2019 Father’s Day event at Dodgers’ Stadium in 2019. From left, Brayden Rorick, Bob Matsumoto, Maya Rorick, Amiko Matsumoto and Robin Rorick. (Photos: Courtesy of Amiko Matsumoto)

Whenever he hears the national anthem, he thinks of the time he spent on the flight decks of naval ships when he served in the Navy, and then he thinks of his Nisei father’s ad.

“It’s very meaningful,” he said. “I feel it.”

To reconcile his patriotism with the injustice his family suffered during WWII, Matsumoto has a mission: Do everything he can to make sure it never happens again.

In the time of anti-Asian hate, Matsumoto thought about the “Yes, we are Americans” ad again.

“I thought about what 120,000 Japanese Americans went through, and I said, ‘This has happened again.’”

The idea came quickly.

He created a design with Lady Liberty, the strength and the voice of America with the tagline, “Anti-Asian Hate is not what I stand for.” In the design, Lady Liberty is staring directly at you, calling on you to put an end to the violence and the fear. To have the Statue of Liberty represent the phrase, how much higher can you go?

Matsumoto’s design has appeared on billboards and buses in New York, Los Angeles and Sacramento. People have hoisted poster versions of the design at “Stop Asian Hate” protests.

Matsumoto’s campaign has also reached millions of Americans through billboard advertising and social media, according to Paul McClure, principal and director of advertising of RSE, who helped facilitate the campaign.

“Bob’s reputation and great work has earned him millions of dollars in donated advertising space to promote this message,” said McClure.

The spike in anti-Asian violence has spurred discussion in the Asian American community about the need for more education and representation. According to a 2020 Morning Consult survey, 62 percent of Asian Americans feel underrepresented in ads.

There’s a long way to go, and for Matsumoto, the fight is personal.

“It’s not about advertising,” he said. “In my case, it’s about leaving something that I think will help make a definite positive change.”

A Block 30 group photo at Manzanar that includes the Matsumoto family.