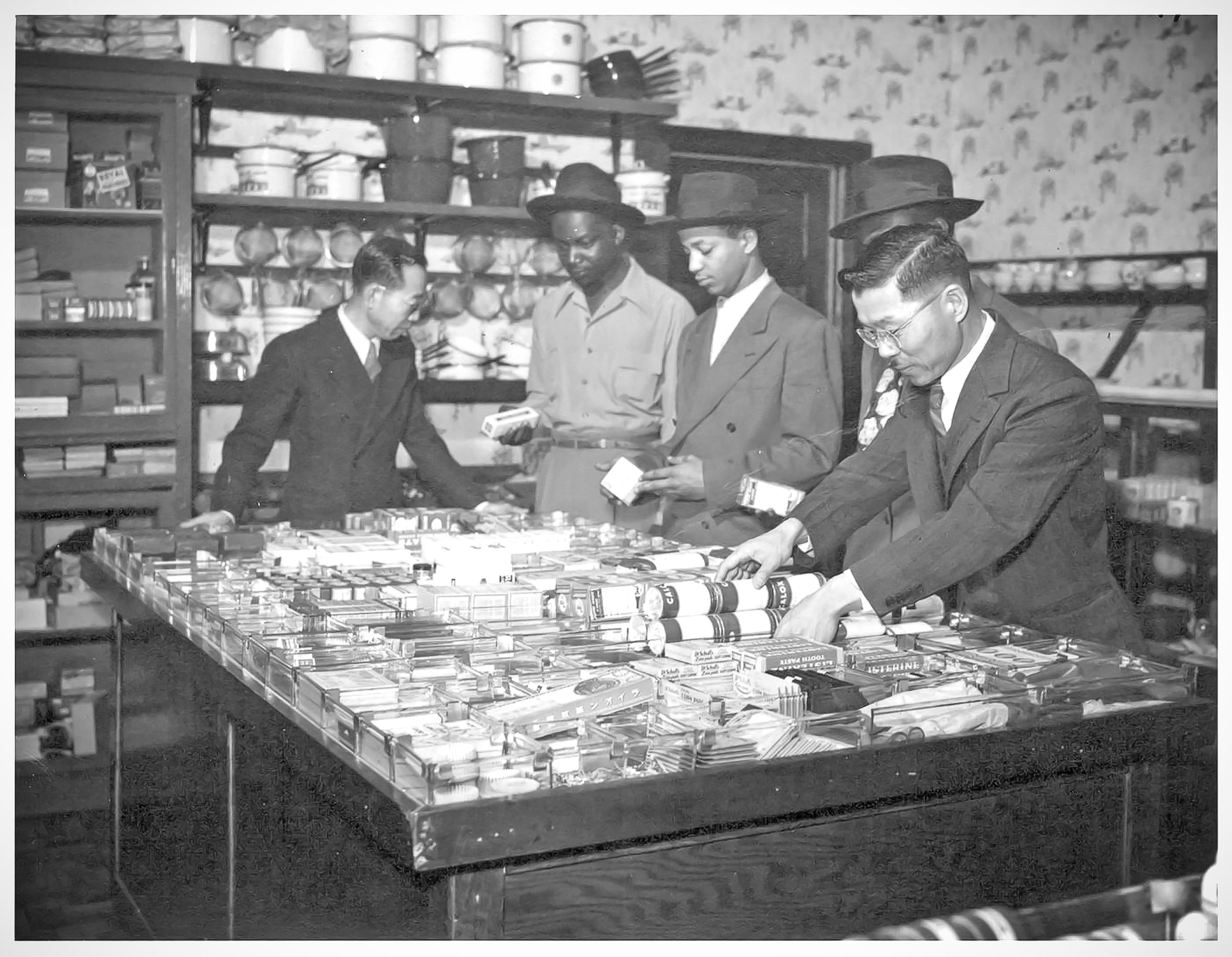

Customers and shopkeepers interact in Little Tokyo/Bronzeville.

Community Intersections are revisited at the 33rd Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival.

By Rob Buscher, Contributor

Ever wonder what became of the homes and businesses that Japanese Americans left behind during the incarceration of World War II?

The downtown Los Angeles neighborhood of Little Tokyo became home on April 29-30 to a site-specific multimedia installation titled “Bronzeville, Little Tokyo” — a project remembering the brief moment in history from 1942-45 when this decidedly Japanese American space became an African-American enclave known as “Bronzeville.”

A joint project between documentary film studio FORM follows FUNCTION and AAPI media advocacy organization Visual Communications, this installation was one of the highlights at VC’s 33rd edition of the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival.

VC’s office is located at Union Center for the Arts on Aiso Street, and its proximity to Little Tokyo made the project more personal to its staff. Abraham Ferrer, VC staff member and exhibitions director of LAAPFF, reflected on its long connection to the neighborhood.

Little Tokyo became home to the multimedia installation “Bronzeville, Little Tokyo” in April to remember the moment in history when the space became home to the African-American enclave known as Bronzeville. (Photo: Julie Wong)

“Among VCers of a certain age, we are acutely aware of this neighborhood’s identity as Bronzeville,” he said. “We produced a historical picture book, ‘Little Tokyo: One Hundred Years in Pictures,’ for the Little Tokyo Centennial Committee in 1984 that talks about Bronzeville in some detail, so approaching the Bronzeville story outside of a staid documentary film format and to go with a sensory, interactive and immersive experience exemplifies the outside-the-box creative strategies that VC has championed and practiced for its nearly five-decade history.”

Special events highlighting aspects of the shared spatial history took place at sites familiar to longtime Little Tokyo residents such as the historic Nishi Building and Union Center. The Nishi Building hosted a mixed-media performance piece called “Memory Bank,” which incorporated audio reactive technology to project digital images as spoken word artists and other individuals shared memories and reflections of Bronzeville in an open-mic environment.

Another aspect of the project was the debut of a three-minute virtual reality animation titled “Bronzeville, Brass, Jazz,” a 1940s dreamscape meant to evoke the spirit of late-night jam sessions and fabled stories about jazz great Charlie Parker during his memorable stay at the Civic Hotel and brief residency at the Finale Club.

The weekend program culminated in a live jazz performance at the steps of the Old Union Church by the Bronzeville Union, a group specially formed for the occasion.

Project Adviser Kathie Foley-Meyer wrote of the neighborhood’s significance, “Bronzeville remains relevant as a strand in the complicated tangle of history in L.A. — a history that is often glossed over or rendered incomplete with the messier details left out.”

This certainly rings true in the case of Bronzeville, as few people even within Little Tokyo are aware of its existence.

The Bronzeville story began with the Emergency Shipbuilding Program, an initiative commenced by the U.S. government in January 1941 — almost a full year before entering WWII. This program aimed to produce enough ships to keep America’s overseas territorial possessions safe amidst the growing conflict of WWII, while also assisting the United Kingdom in noncombat roles through its merchant navy. In May 1941, Terminal Island in South Los Angeles became home to the California Shipbuilding Corp., also known as CalShip.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the U.S. shipbuilding industry was at an all-time high as defense contractors worked in a mad rush to replace the damaged ships of the United States’ Pacific Fleet.

With a majority of the service-aged men in L.A. choosing to join the military after Pearl Harbor, the resulting labor shortage opened up a slew of new opportunities for African-Americans looking to migrate West, away from the historically slave-owning Southern states. By 1944, more than 7,000 African-Americans were employed by CalShip alone.

During the 1940s, L.A. real estate was governed by strict housing covenants that prohibited the incoming African-Americans from moving into white neighborhoods. Thus, the recently vacated Little Tokyo was identified by city planners as a settlement site for this community. Soon after relocating, the new residents renamed their neighborhood as “Bronzeville,” after the celebrated African-American business district in South Chicago.

For the next four years, Bronzeville would become a vibrant working-class neighborhood home to overcrowded workers’ quarters, jazz clubs and a number of African-American-owned businesses. The nightlife was particularly notable for its many “breakfast clubs,” consequently named because they stayed open until the next morning.

As WWII came to an end, labor needs shifted to other industries, and many African-Americans moved out of the neighborhood. Once JA families began returning from camp, many of the white property owners either canceled or refused to renew the leases held with their African-American tenants. Although Japanese and African-Americans cohabitated this space for several years through the end of the decade, Bronzeville and its African-American residents soon became a footnote in the history of this space.

Interestingly, Little Tokyo was not the only case in which African-Americans began inhabiting Japantowns during WWII. The California State Division of Immigration and Housing states in its 1943-44 Biennial Report, “Negroes are moving into the deserted Japtown districts of our metropolitan centers in vast numbers, and conditions of sanitation are generally poor, and overcrowding is a major difficulty. … We have succeeded in cleaning out several of the smaller abandoned Japtown districts throughout California, and through abatement and misdemeanor prosecutions, we have had a large number of old dilapidated frame shacks razed to make way for new buildings.”

Sadly, this combination of institutional racism in government policy and gross neglect by a majority of white Japantown property owners led to a culling of California’s many Japantowns from a prewar number of nearly four dozen to just three: Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Jose.

In subsequent decades, JAs have undertaken tremendous efforts to preserve and maintain the legacy of these last surviving Japantowns, persevering against identity erasure and gentrification in all three cities. Somehow, the intersectional histories of JAs and African-Americans seems to have been lost, which is why “Bronzeville, Little Tokyo,” is so important.

Said Ferrer, “This intersection of Japanese American and African-American communities would play itself out for decades after WWII, when these communities established homes in the nearby Seinan District (what we know as Crenshaw, at the foot of Baldwin Hills). During the 1940s, [Bronzeville] would become known as a second hub of African-American culture and society, rivaled only by Central Avenue in South Central L.A.”

As today’s social justice campaigns seek to build solidarity amongst communities of color, a renewed interest in the intersectionality of these communities has emerged.

Maya Santos is a community organizer, neighborhood advocate and filmmaker who co-founded FORM follows FUNCTION. The consortium of artists responsible for this project relied heavily on Santos’ vision as creative director, as well as a nuanced understanding of the neighborhood.

About her relationship to Little Tokyo, Santos wrote, “Having screened my first short film at Union Center and years later making a short doc about how the church became an arts space, I learned a lot about Little Tokyo through this one place. I have always been drawn to the history and intersectionality of people of color in Little Tokyo. The resilience of community and layers of history is fascinating and inspiring, and I think learning about Little Tokyo as a place tells us a lot about what L.A. was, what it still is and can be. I’m inspired by the intergenerational and multiethnic community here and learned a lot about how generations work together, inclusive of a 130-plus-year history yet open to something new. Though it’s not easy to propose things people have sometimes never heard of, I’m in awe at [the neighborhood’s] openness that has allowed us to experiment in the ways we have.”

Much of Santos’ work over the past several years has been connected with Little Tokyo. Bronzeville was the original inspiration for her 2016 project “Interactive Little Tokyo,” which was featured at the 32nd edition of LAAPFF, but she decided to separate the story into smaller strands given its scope and limited resources. The 2016 portion consisted of a VR piece called “Walking With Grace” and video map installation “312 Azusa Street,” both of which highlighted overlooked Japanese American histories and local perspectives within the neighborhood.

The success of “Interactive Little Tokyo” helped pave the way for her most recent project. Santos wrote, “[We] learned from the 2016 project that there was a unique intergenerational interest in VR and historic site-specific installations that could be expanded upon. Our partnership with VC was awesome, and the festival is a great platform, yet there was room for more collaboration and partnership through which other organizations could benefit from being part of this creative endeavor telling more of Little Tokyo’s story.”

Given the significance of jazz during the Bronzeville years, finding the right partners for the closing musical performance was paramount to its success. That is why Santos entrusted this role to talented multi-instrumentalist composer and bandleader Dexter Story.

Story was a clear choice, having spent much of the last 15 years at the epicenter of L.A.’s popular music culture as a touring jazz musician and former marketing director at Def Jam Records.

Asked about his involvement in the project, Story wrote, “When Maya Santos invited me to put together the music for ‘Bronzeville, Little Tokyo,’ I started reading articles and listening to music from the period. I hadn’t heard of Bronzeville, but I knew about WWII internment. I allowed the many facets of that Japanese/African-American experience inform my composing and out came ‘The Bronzeville Little Tokyo Suite.’ The members of Bronzeville Union were handpicked for their professionalism and heavy involvement with the Los Angeles live music scene. Coincidentally, pianist Mark de Clive-Lowe is half-Japanese, so his involvement provided a special element.”

Since there are few individuals remaining who can give a firsthand account of Bronzeville’s history, an impressive amount of research went into the conceptualization of this project. Santos wrote, “Because there are so few quality archives of Bronzeville, we knew we needed to create art out of fragments of history. [Eddy Vajarakitipongse of yaknowlike studios] came up with the audio reactive projection technology and mapped it out in the space, and I came up with the open mic and coined the [‘Memory Bank’] name. Together, it was a success in creatively recontextualizing Bronzeville history with the soul that people brought through their memories.”

While “Bronzeville, Little Tokyo” existed for only a brief period of time, it seems fitting given the fleeting nature of this neighborhood’s identity as Bronzeville. Perhaps with additional interest and funding, this project can eventually live in a more permanent location. In the meantime, video segments recorded during the “Memory Bank” installation will soon be available online, and the VR piece “Bronzeville, Brass, Jazz” is accessible via YouTube.

Visit www.fffmedia.com/bronzeville for more information on the project and www.vconline.org/latest-news/releasing-bronze-bass-jazz-into-the-world for instructions to watch the VR piece.