Lives Remembered for Achievements, Lasting Legacies

By P.C. Staff

2020 was a year that saw several barrier-breaking Nikkei women die and before it ended, two more distaff Japanese Americans were added to that mournful list: attorney Rose Matsui Ochi on Dec. 13 at 81 and former California Legislature staffer Georgette Imura on Dec. 17 at 77.

Ochi, who was already battling health issues, was fighting COVID-19 for the second time when she died in Los Angeles, just two days short of her birthday.

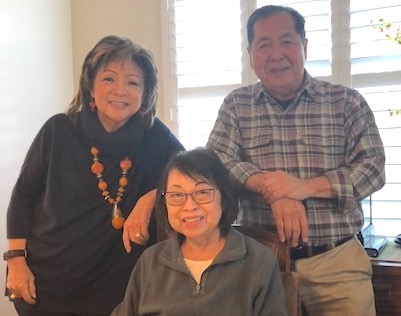

Imura (Photo: Courtesy of Aaron Imura)

Imura succumbed to lung cancer in Sacramento, Calif., after a three-year battle with the disease.

Ron Wakabayashi, who served as JACL’s national director when Imura was at the California Legislature, praised Imura and her colleague, Maeley Tom, for their work that helped the Asian American community.

Imura, who was born Georgette Yamamoto in 1943 while her family was incarcerated at California’s Manzanar War Relocation Authority Center, was known as a politically savvy behind-the-scenes operator at the state capital and began her career in 1967 working for state Sen. Leroy Greene.

“Georgette was a workhorse. She would look like it, ‘How do we get this implemented, what do we need to do?,’ ” said Wakabayashi. “All of the logistics and the planning — if I wanted to carry something out, it would be Georgette.”

Imura also worked for Assemblywoman Yvonne Brathwaite and Assemblyman Julian Dixon. Later, she became Calif. state Sen. Diane Watson’s chief of staff, and following that, she served as the director of the Office of Asian Pacific Affairs for state Sen. David Roberti when he was the Senate president pro tempore.

During her career, Imura noted the dearth of Asians involved in state politics and with another Asian American woman and fellow state legislative staffer, Maeley Tom, co-founded the Asian Pacific Youth Leadership Project, a workshop designed to familiarize Asian and Pacific Islander Americans with California’s political process, and inspire and encourage participation in public service and politics. Imura would also mentor younger Asian Americans, and she later used her leverage to help with the Japanese American redress movement.

Maeley Tom, Georgette Imura, Ron Wakabayashi

Tom and Imura also helped lead the successful opposition to the appointment of U.S. Rep. Dan Lungren (R-Calif.) from becoming California’s state treasurer. Lungren who was the vice-chairperson of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, opposed the monetary component of Japanese American redress.

Wakabayashi also credited Imura and Tom with raising awareness at the state and federal level to what is now known as hate crimes toward Asians, aka anti-Asian violence.

After a 28-year career in the California Legislature, Imura became a political consultant via Liberty Consulting and helped pass legislation to preserve the state’s remaining Japantowns. She also served on the boards of several community organizations.

Georgette Imura is survived by her husband, Roy Imura, sons Todd and Aaron and four grandchildren.

Ochi

Meantime, Ochi’s place in history was sealed on Aug. 10, 1988, the day President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. During the ceremony and with Ochi present, Reagan said, “And now in closing, I wonder whether you’d permit me one personal reminiscence — one prompted by an old newspaper report sent to me by Rose Ochi, a former internee. The clipping comes from the Pacific Citizen and is dated December 1945.”

Reagan’s allusion was to an article published in the Pacific Citizen about the posthumous presentation of the Distinguished Service Cross by Gen. Joseph Stilwell to the family of Kazuo Masuda, who was killed in action as a member of the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team. The 1945 article also mentioned Reagan’s presence at Masuda’s ceremony.

Even without that call-out by Reagan, Ochi’s actions and achievements in her nearly 82 years of life would be notable.

Born Takayo Matsui in East Los Angeles, Ochi spent some of her childhood peripatetically, first when her family was uprooted to the Santa Anita Detention Center in California, followed by incarceration at the Rohwer WRA Center in Arkansas, where she was given the moniker “Rose” by teacher. She acquired the surname Ochi after marrying Thomas Ochi.

Prior to earning her law degree in 1972 from Loyola Law School, Ochi graduated from UCLA in 1959 and earned an M.A. from Cal State Los Angeles in 1967. She served as a public school teacher in both the Montebello Unified School District and the Los Angeles Unified School District.

After earning her law degree, Ochi was a founding member of the Japanese American Bar Association (JABA), and she served on the L.A. County Bar Association’s board of trustees. She also was a presidential appointee to National Commission on Immigration & Refugee Policy; the attorney general-appointed vice chair of the Department of Justice’s National Minority Advisory Council, and an appointee to the L.A. County Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee.

Under Los Angeles Mayors Tom Bradley and Richard Riordan, Ochi was the executive director of the Mayor Office of Criminal Justice Planning. She also was staff attorney at USC’s Western Center on Law & Poverty.

Under President Jimmy Carter, she served on the Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy or SCIRP. Under President Bill Clinton, she served as the associate director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy and later was the director of the Department of Justice’s Community Relations Service, unanimously approved by the Senate.

Later, Ochi would serve as the executive director Cal State L.A.’s California Forensic Science Institute. She also became the first Asian American woman police commissioner when she was appointed to the Los Angeles Police Department’s Police Commission.

Ochi also was involved in JACL at the local, regional and national levels, as a member of the East L.A. Chapter’s board, a consultant for the Pacific Southwest District’s Redress Committee, a member of the board and executive committee of JACL-LEC, program chair for the PSW-LEC’s fundraising dinner and chair of the PSW U.S.-Japan Relations study group. She was also a national JACL VP.

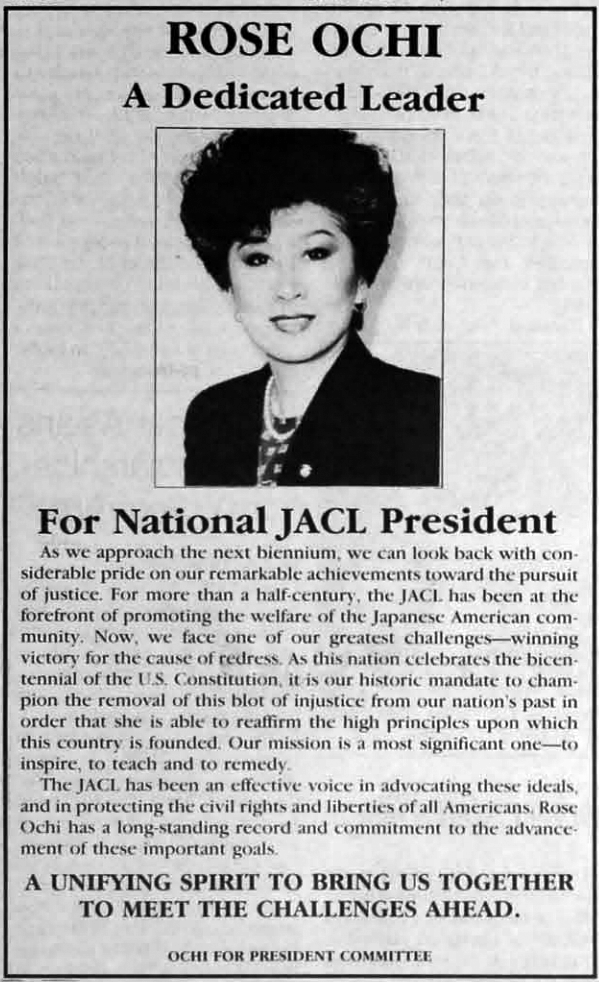

This advertisement for Rose Ochi’s candidacy for national president of JACL ran in the Pacific Citizen in 1986.

In 1986, she ran for JACL national president, narrowly losing at the Chicago National Convention to Harry Kajihara, 62-1/2 to 59-1/2.

Recollecting on Ochi’s JACL leadership aspirations, Wakabayashi said, “I think Rose was too far ahead of her time for JACL folks. Even Lillian [Kimura, who was JACL’s first woman national president], she had a hill to climb, too, just being a woman. I think Rose had even more of one.”

Wakabayashi noted how her opposition mocked Ochi’s hair, which she was streaked with gray. “I think there’s a theme in there of expectations of many Nisei men of how Nisei women should be. Rose was not the usual mold. They were kind of uncomfortable with strong women.”

Working with Manzanar Committee co-founder and chair, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, Ochi provided the legal expertise needed to help with having the former WRA Center become a national historic site.

The Manzanar Committtee’s Bruce Embrey lauded Ochi’s role with the organization. He said, “When Rose followed my mother as chair of the congressional Manzanar Advisory Commission, she helped navigate the federal bureaucracy as the site was being built, using many of her political connections to expedite things. After the opening of the Manzanar National Historic Site, Rose continued to work with both our Committee and with the newly-created Friends of Manzanar.”

The Manzanar Committtee, in a statement, said, “Rose will be deeply missed.” The Japanese American National Museum, meantime, thanked Ochi for her “contributions to our community and our nation.” JABA also lauded Ochi, stating, “Rose Ochi’s life and contributions to the Japanese American community, the City of Los Angeles, and our country are remarkable and deserve remembrance.

Although Ochi and her husband, Thomas, never had children, Wakabayashi said through her work, Ochi mentored many younger people who she treated as though they were her surrogate children, including Darlene Kuba, who created a tribute website to Ochi at forevermissed.com/rose-takayo-matsuiochi/about.

In the interim since her passing, there have been many political tributes to Ochi’s life. The latest came on Jan. 13 from Los Angeles City Councilman Kevin de Leon, who introduced a motion to name the intersection of E. First and San Pedro streets Rose Ochi Square.

On Jan. 11, when the California Legislature adjourned, it did so in memory of Ochi. Said Assemblyman Al Muratsuchi: “Rose Ochi was a strong, beautiful woman who broke many barriers as the first Japanese American woman to serve in the highest levels of public service under President Bill Clinton and Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley, among many other leadership roles she served in. She inspired and supported many women and men like me to continue her legacy of service.”

Recalling the lives and contributions of both Imura and Ochi, Wakabayashi praised them as “bad ass,” and lamented, “I’m lost without them now.”