Michelle Sakazaki of Kazumi Wines (Photo: Courtesy of the Sakazaki Family)

Michelle Kazumi Sakazaki honors more than a century

of Japanese American farming with every bottle of

Napa-grown Koshu.

By Lynda Lin Grigsby, P.C. Contributor

“It was destiny,” said Michelle Sakazaki about her decision to nurture Koshu grapes from vine to wine. (Photos: Courtesy of the Sakazaki Family)

The Koshu grape is a delicate contradiction — thick-skinned, yet fragile. In its native Japan, where the grape has been cultivated for thousands of years, some growers protect the fruit by gently crowning the pink clusters of grapes with folded paper hats.

Thousands of miles from its ancestral home, Koshu has found an unlikely advocate in California. Kazumi Wines is the first boutique brand in the United States to produce Koshu wine from American-grown vines.

Kazumi wines

Michelle Kazumi Sakazaki, the Yonsei proprietor of Kazumi Wines in Napa Valley, Calif., sees facets of herself in the grape. Both are descendants of transplants from another land. Both are shaped by new soil and finally appreciated for what they became — Japanese Americans.

In Napa, Michelle oversees more than five acres of thriving Koshu grape vines. The natural question arises: Do the American vines also wear paper hats?

“No, we don’t use hats for our Koshu grown in Napa,” said Sakazaki, 46.

In a world plagued with increasing incidents of unpredictable weather, Koshu’s thick skin makes it a varietal of the future. Its American brand ambassador also charts a trailblazing course. In California’s wine world, Sakazaki represents a new wave of Japanese American leaders who are leveraging ancestral farming legacies and business acumen to create products that represent their cultural roots.

“She’s really expanding what is possible for JA people in the wine industry,” said Ken R. Minami, a wine industry veteran and vp and deputy general counsel of Delicato Family Wines, which is based in Napa.

Rooted Legacies, Unwritten Histories

For Sakazaki, who was once a fashion designer, the path to the wine industry was circuitous. She worked for brands such as Missoni and Armani Exchange but longed for change. The verdant hills of Napa — where her father, Jack Sakazaki, had established a start-up wine club business — beckoned.

Kazumi Koshu is more complex than its Japanese counterpart.

In 2009, Michelle Sakazaki began working with her father as the general manager of the 90 Plus Wine Club, an international subscription service that curates and exports premium California wines to members in Japan and Asia.

But she wanted more. She wanted something to call her own.

So, Sakazaki launched Kazumi Wines in 2015, making her presence as a Japanese American woman in the wine world feel downright revolutionary. The number of Asian American Pacific Islander female leaders in the industry could be counted on one hand — despite the Japanese American community’s storied history of innovation in wine and agriculture.

“It was destiny,” said Sakazaki about her decision to nurture Koshu grapes from vine to wine.

Sakazaki’s story is not an outlier — it’s a continuation.

Japanese Americans have long tilled the soils of California’s farmland and shaped the state’s agricultural history. But their contributions are often obscured.

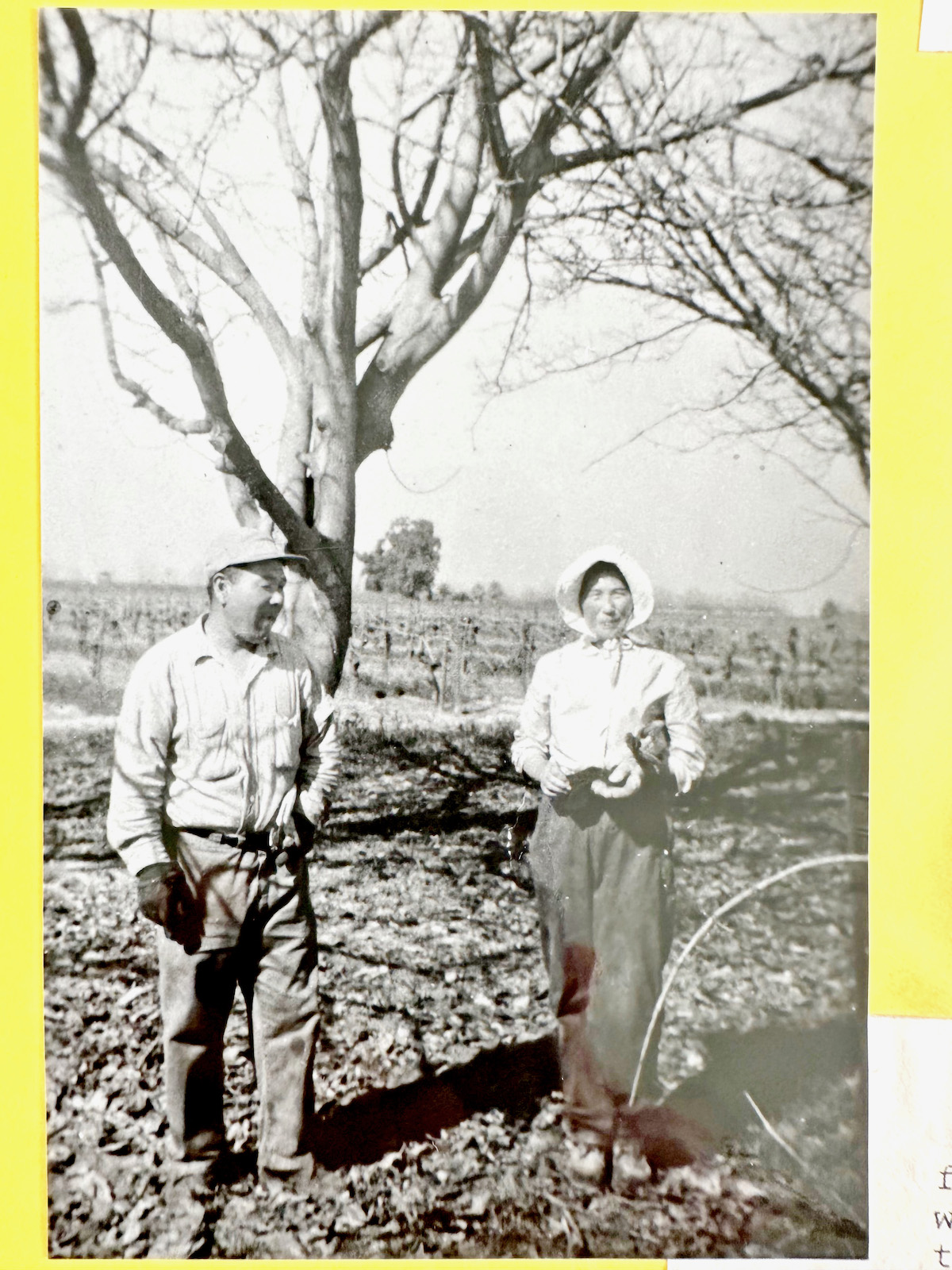

Michelle Sakazaki’s paternal grandparents prune grape vines.

In the early 1900s, Kanaya Nagasawa, known as the “Wine King,” turned the Santa Rosa, Calif.-based Fountaingrove Winery into one of the state’s most influential. In Sacramento, George Shima became known as the “Potato King” for his innovative farming techniques. In Gilroy, before the beginning of the Second World War, Issei farmer Kiyoshi Hirasaki became known as the “Garlic King” for being the country’s largest garlic grower.

“I mean, we have almost everything covered,” joked Minami, 64, about the dominance of Japanese American farmers.

For generations, the Sakazaki family traveled between Japan and the United States. Their migration stories are shaped by global and domestic upheaval — war, anti-Asian sentiment and mass incarceration.

Michelle Sakazaki’s paternal Issei great-grandparents, Sakuzo and Sueme Shimasaki, worked as migrant farm workers before settling in Los Angeles before World War II, where they ran the produce section of a supermarket chain called the Piggly Wiggly. In 1942, their lives were upended when both Sakuzo and Sueme were incarcerated at Amache near Granada, Colo.

Two generations later, Jack Sakazaki, who grew up in Fresno, spent summers picking fruit, before moving to Japan to run a sports marketing company.

Being of the land runs in the family — so is running a family business.

The kanji characters for Kazumi mean “harmonious beauty” or “peaceful beauty.” Kazumi is Michelle Sakazaki’s Japanese middle name — a blend of her parents’ Japanese names, Kazunori and Mayumi.

But the wine company’s origin wasn’t always harmonious. To the people who know them best, the father-daughter pairing as business partners was improbable.

“We were all really nervous about them working together,” said Margot Sakazaki, Michelle’s older sister. “Are they gonna’ kill each other?”

The friction in their relationship is attributed to their similar personalities. Both are stubborn, driven and competitive. Both have innovative spirits.

“We explode, and then we’re fine,” said Michelle Sakazaki. “And then we carry on as if nothing happened.”

They have the right personalities for the wine business, said Margot, 48. “You kind of need to have that bigger personality.”

To launch Kazumi Wines, Michelle Sakazaki bought a half-ton of Sauvignon Blanc grapes — a venture that made her father wring his hands with worry. She could make 25 cases of her own wine.

It’s 25 cases, she assured him. Not much by wine production standards.

“If I don’t sell it out, mom and I will drink it. No big deal,” she said.

All the bottles sold out.

A New Expression of Identity in Every Bottle

Japanese Koshu, a lighter citrusy white wine, is largely unknown to American consumers.

After a 2017 wildfire swept through Napa Valley and destroyed community homes and vineyards — including the Sakazaki’s backyard vines (their house was spared) — Jack Sakazaki searched for viable replacements to graft onto his surviving vines. At the University of California, Davis, he discovered Koshu, and his body tingled with excitement. It’s the most well-known of three native varietals from Japan.

Jack Sakazaki purchased all the Koshu canes they had available. What if they could introduce Americans to Koshu wine?

He told every winery owner and winemaker about the Koshu vines and eventually found two growers in Napa Valley who agreed to grow the Koshu grapes. Kazumi makes wine in partnership with growers without owning a winery, an increasingly common approach that allows independent winemakers and boutique brands to produce high-quality wine without the massive capital investment required to own a vineyard and winemaking facilities.

Napa Koshu grapes in 2023. Koshu’s thick skin makes it a varietal of the future.

Today, Koshu grapes grow in 5.5 acres across South Napa and Oak Knoll.

Michelle Sakazaki’s Koshu is not a copy of its Japanese counterpart — it is a reinvention and a Japanese American story in a bottle.

Koshu harvest

The Napa version has more body, said Minami. When he received a bottle of the first release of the Kozumi Koshu, he also bought some Japanese Koshu to compare the two. The Japanese version is refreshing but not necessarily complex.

“Kazumi, to me, had more complexity, so it had a little more body,” said Minami. “The pioneering aspect of this wine is the attraction to me.”

In 2024, Kazumi produced 900 cases of Koshu — small by production standards.

Now, Kazumi is planning to expand the planting of Koshu vines in Lodi. More sparkling Koshu is also in the works. To scale the business, Michelle Sakazaki works with an all-Asian team, including winemaker Kale Anderson, who is of Filipino descent.

As she deepens her roots in the industry, Sakazaki is not alone. A growing number of Asian American and Pacific Islander winemakers, sommeliers and entrepreneurs are reshaping the wine landscape. This year, a group of industry professionals established the Asian Wine Association of America, an organization aimed at increasing visibility, mentorship and representation for AAPI voices in the wine industry.

Michelle Sakazaki and Minami both serve on the AWAA’s board of directors.

Harvesting Koshu grapes

She doesn’t work the land, but she is from it. In the shade of the vines or the hustle of the business, she often thinks about her maternal grandmother, Hatsue Doioka, with whom she shared a close relationship. Hatsue saw Michelle in action taking notes, tasting and working with growers.

This business was meant for Michelle, said Hatsue, who died in 2014. Others would say Michelle Sakazaki is meant for the wine business.

Some vines, it turns out, were always destined to grow here.

For more information, visit www.kazumiwines.com.