The Manzanar-born UH professor recalls his youth in the SoCal beach city.

By P.C. Staff

“Ogawa from Obama.”

That’s how Professor Dennis Ogawa said his University of Hawaii students like to jokingly introduce him. It’s actually a bit of an exaggeration, since Ogawa, a UH humanities professor with more than 52 years in that post, was actually born at the Manzanar War Relocation Authority Center in California’s Inyo County, more than 200 miles from Los Angeles.

But Ogawa does indeed have familial roots in the Japanese beach town on the west coast of Japan’s Fukui Prefecture — and by living near the ocean, first as a lad in Santa Monica, Calif., and later, in Honolulu, Hawaii — he has kept true to his beach town roots in three far-flung locations.

He shared that and other memories during a Feb. 10 Zoom webinar sponsored by the Santa Monica Conservancy titled “Nisei Memories: A Second-Generation Japanese American Recalls Life in Santa Monica After His Family’s Release From Manzanar.”

Ogawa’s installment was part of the Conservancy’s series titled “Stories From the Diverse Communities That Shaped Our City.”

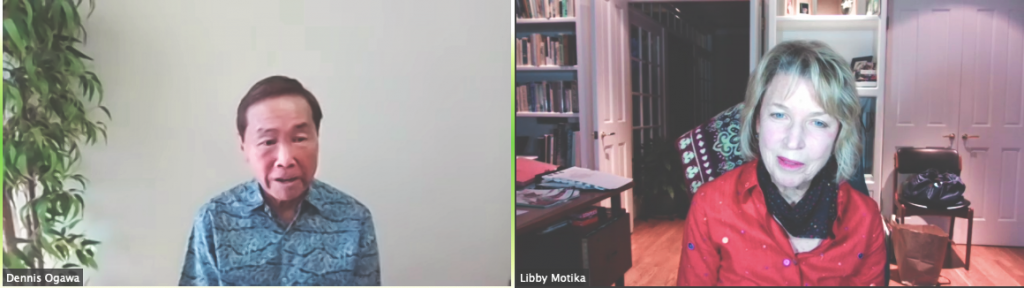

Before Ogawa began his “talk story,” moderator Libby Motika of the Conservancy shared how first-generation Japanese immigrants had a history in the beach adjacent city going back to the early decades of the 20th century, when Issei founded a fishing village north of the long-demolished Long Wharf and Santa Monica Canyon, on what would now be some very pricey beachfront property in the tony resort town.

Dennis Ogawa and Libby Motika converse during the Zoom webinar.

Motika noted that the village at its peak had some 300 residents and the Issei fishermen hauled in more than 30 tons of fish daily, which was then sent by train to downtown Los Angeles, not far time- and distance-wise from where a young Sessue Hayakawa was “discovered” in a stage play by silent era producer Thomas Ince, who was tipped off by Hayakawa’s future wife, Tsuru Hayakawa.

Hayakawa’s stardom was launched when Ince tapped him for three silent pictures — “The Typhoon” (1914), “The Wrath of the Gods” (1914) and “The Sacrifice” — some shot not far from the fishing village.

The fishing village was condemned in 1920 a few years after a devastating 1916 fire. The Japanese residents scattered, some to as far away as Terminal Island, with others staying in Santa Monica.

In the years before World War II, Ogawa’s Nisei mother and Issei father operated a small grocery store in Santa Monica, and they were often helped by an elderly Black neighbor from the south who lived in a shack next to the store. Ogawa later came to know him as Mr. Magnum. The elder Ogawa and Magnum became friends.

But with the United States’ entry into WWII, the Ogawa family would lose their Santa Monica home and business when they and many thousands of other ethnic Japanese were removed from the West Coast and incarcerated in 10 different WRA Centers, Manzanar in the case of the Ogawas and other local Japanese families.

“My dad, when the war was over and we were released from the concentration camp,” Ogawa said, “wanted to go back to Santa Monica.” There was one problem: After the war, there was no housing available. “It was almost impossible to find a place.”

Still, Ogawa said his father was determined to do whatever he needed to return, taking a job as a dishwasher. Ogawa’s mother, meantime, found work cleaning houses. The Ogawas also found a place to live: With Mr. Magnum, in his one-room shack.

“It had a little running water and a toilet,” Ogawa said. “My mom and my dad, they slept on the floor and Mr. Magnum and I, we slept on the floor under the kitchen table. To me, it was kind of cozy.”

Magnum was Ogawa’s babysitter as his parents worked. “He was actually the one who raised me in the early days,” Ogawa said, which is why to this day he says he pronounces certain words with a southern Black accent.

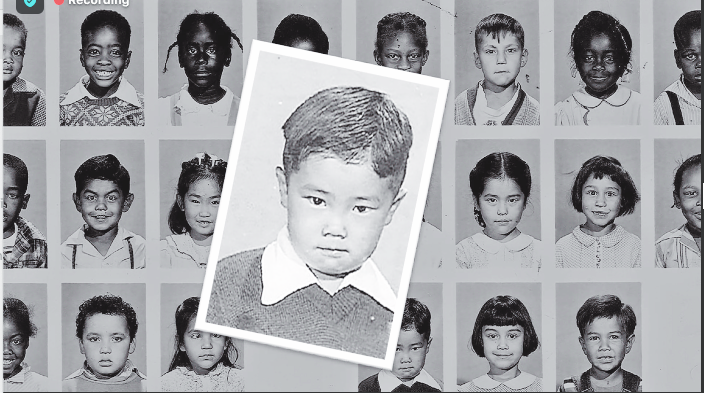

Dennis Ogawa when he was in elementary school.

As Ogawa attended Santa Monica schools, Ogawa would learn a valuable lesson that paid off as a young man. As a kindergartner at Garfield Elementary School, which was mostly Latino and Black, he recalled how his teacher, Mrs. Hamilton, bought a Christmas tree to the class that the students decorated.

But during recess, as the kids played kickball, the ball bounced off the concrete through the classroom’s open window — and it knocked over the tree, demolishing all the work that had been done. “We thought we were going to get it. We were scared,” Ogawa said.

Instead, the teacher later told them they were good kids and that accidents happened.

“She didn’t really even talk about the Christmas tree, but we all knew, and she wasn’t mad. And that stuck with me.”

A few years later, as a student at John Adams Junior High School, Ogawa was tripped during physical education class in a footrace by another student, and he wiped out on the concrete, resulting in his arms and knees getting bloodied. “Some of my buddies, they were going to kill the guy who tripped me,” Ogawa said. When the PE teacher arrived with a couple of the school nurses, Ogawa just said, “Accident.”

When it was time to graduate from junior high, Ogawa got a surprise from the PE teacher, who called him out by name to give him the school’s first-ever Sportsman of the Year award. “I was in shock,” Ogawa said. “I was speechless.”

When it was time for college, Ogawa said, “I was very fortunate, I got into UCLA.” In his application, he indicated that he wanted to become a PE teacher. “As I look back, I think part of the reason I was accepted at UCLA was because of my Sportsman of the Year award at John Adams.”

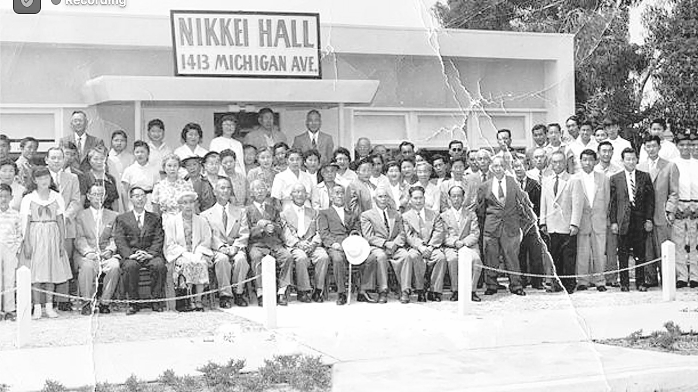

Photo taken in front of Santa Monica Nikkei Hall upon its completion in 1957. (Photo: The Rafu Shimpo)

One of the common denominators for Santa Monica’s Japanese American community the Nikkei Hall, a building at 1413 Michigan Ave., built by the Nikkei Jin Kai, near the city’s Woodlawn Cemetery. Ogawa’s father was one of the organization’s active members.

Ogawa at the Ireito monument in Santa Monica.

“Nikkei Hall was like the gathering place,” Ogawa recalled. “My dad was part of the group that helped build the monument, at Woodlawn Cemetery, of the Issei.” Ogawa was referring to the Ireito or memorial tower, a white granite monument at Woodlawn that was built in 1959 and rebuilt after it was damaged in the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

Ogawa remembered how local families would meet at the Nikkei Hall and then take buses to other locations, like Lake Arrowhead or Griffith Park for picnics. Sometimes there were non-Japanese guests who would join them, Ogawa said. One of those guests was actor Gabby Hayes.

After the war, however, despite the construction of the Nikkei Hall, Santa Monica’s Japanese community was unable to return to its prewar numbers, much less surpass them, unlike some other pre-existing enclaves such as what is now Sawtelle Japantown — and in 2018, a decision by the four remaining Nikkei Jin Kai members was made to disband the organization that owned it and sell the property.

Although it had been reported that a TV and movie production company would buy it, during the webinar the Conservancy’s Motika noted that there had been some new developments.

“Last summer, the City of Santa Monica approved an affordable housing project on the site of the landmark hall. The original structure will be integrated into the new design to enhance public awareness of the historic site,” Motika said.

This occurred after the city designated Nikkei Hall a historical property, which paved the way to making a deal with San Rafael, Calif.-based EAH, a nonprofit developer of affordable housing for low-income people and families.

A rendering of the proposed development (Photo: EAH)

Now, the original Nikkei Hall will be part of a 58-unit affordable housing development for homeless people, at an estimated cost of more than $34 million. EAH bought the property with a $3.8 million loan from the city’s Housing Trust Fund.

At UCLA, Ogawa did become a PE major and an English minor, and that “led to the field of communications for me and eventually a Ph.D. in communications.” That was in 1969; while at UCLA, he was one of the founders of the Asian American Studies Center.

After becoming a professor at the University of Hawaii and the former chair of its American Studies Department, Ogawa focused on Japanese American Studies, Television and Ethnic Identity and Multicultural Studies. He would also author several books and would receive from the emperor of Japan the Imperial Decoration Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Ray with Neck Ribbon, in recognition of his role in the development of Japanese studies in the U.S. He also served as a founder and the chairman of Hawaii’s Nippon Golden Network, a pay cable service.

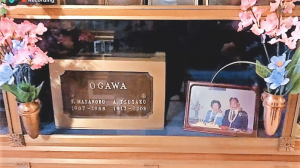

Still, Santa Monica is one of Ogawa’s furusato or hometowns. He said he tries to return at least once a year to visit his parents’ remains, which are interred at a niche at Woodlawn. “I’m really thankful for being able to share some of these memories,” Ogawa said.

He also remains dedicated to the “Ogawa from Obama” ethos.

The niche for Ogawa’s parents’ remains at Woodlawn cemetery.

“Santa Monica Beach is where I grew up,” Ogawa said. “Two of my buddies, I scattered their ashes there, and I will be joining them when I pass away. Part of my ashes will be scattered in Santa Monica waters. But my ashes will also be scattered on a beach in the Waikiki area … and the last part will be scattered at Obama.”

The Santa Monica Conservancy posted a YouTube video of the webinar at tinyurl.com/58b9y7vb. To learn more about the history of Japanese people in Santa Monica, visit tinyurl.com/9zoiobp1. To support the Santa Monica Conservancy, visit smconservancy.org.