As the JACL National Convention nears, here’s a look back on the ‘Father of Redress’ and his organizational connection.

By JACL Convention Committee

The National JACL Convention held in 1978 in Salt Lake City, Utah, at the Little America Hotel — where this year’s National JACL Convention will also be held from July 31-Aug. 4 — is where the Redress Movement really took shape.

It took 10 years of dedicated effort before the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which allowed redress for those people of Japanese descent who were forcibly removed from their West Coast homes and unjustly incarcerated in American concentration camps during World War II.

Many younger JACL members do not know much about the history behind the Redress Movement.

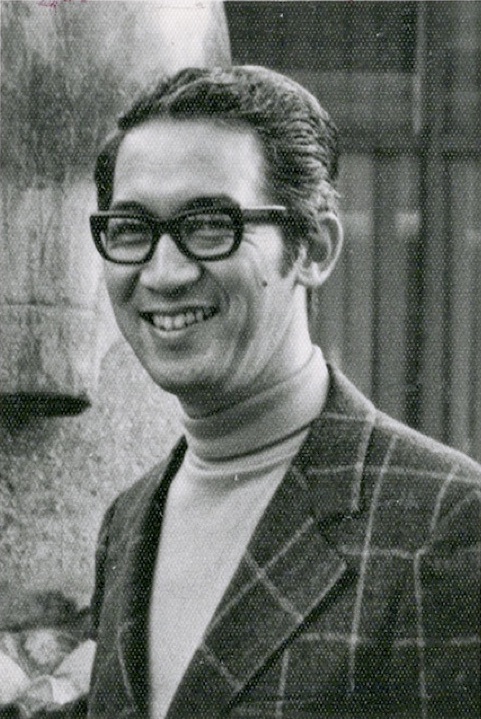

Edison Uno in January 1974 (Photo: Pacific Citizen)

The Redress Movement was actually begun many years earlier. Largely considered to be the “Father of Redress” was Edison Uno, an activist and lecturer at San Francisco State University. He spent and gave his life working for civil liberties and equal justice. Uno had tried for years to gain support for the Redress Movement.

Uno was born in Los Angeles in 1929, one of nine siblings. Around the start of WWII, he was a very young teenager. Uno’s oldest brother worked for the Japanese Army Press bureau before the war, and he had other brothers who volunteered for the U.S. Army.

His father had been arrested by the FBI after Pearl Harbor and was taken to the Crystal City Camp in Texas. However, Uno and the rest of the family were incarcerated at the Granada Camp in Colorado; Uno was then transferred to Crystal City to reunite with his father.

Because of his oldest son’s activities in Japan, Uno’s father was not released from the Crystal City camp until September 1947. Since he did not want to abandon his father, Uno remained in Crystal City even after the war had ended. When he finally left the Crystal City Camp, the official in charge told Uno that after 1,647 days in prison, he was the last American citizen to be released.

Uno returned to Los Angeles and joined the JACL in 1948. He became the youngest chapter president in JACL’s history in 1950. He later attended UC Hastings College of Law in San Francisco, but he had to withdraw because of poor health.

Uno suffered a stroke at the age of 28 and was told by a doctor that he would not live past the age of 40. But Uno did not let his health problems limit his involvement, and he became a champion for the cause of civil rights and social justice.

Uno was married to Rosalind Kido, the daughter of Saburo Kido, the wartime national president of the JACL.

Working long and hard to remedy the injustice that Japanese Americans faced when they were forced into the mass incarceration in the American concentration camps, Uno wanted the government to pay a per diem amount to all those who had been unjustly imprisoned.

The National JACL passed a resolution proposed by Uno at its 1970 National Convention in Chicago to seek redress. However, not a lot of progress was made, though President Gerald R. Ford did issue Proclamation 4417, “An American Promise,” on Feb. 19, 1976, which rescinded Executive Order 9066. (Signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on Feb. 19, 1942, this order authorized the incarceration of Japanese Americans and people of Japanese descent in American concentration camps located in desolate areas throughout the U.S.)

Uno regularly wrote a column called “A Minority of One” for the Pacific Citizen newspaper. Seeking redress and other issues of importance to Uno and civil rights were not always popular. He stated that he often felt like he was a minority of one in the work that he did. He worked tirelessly for the sake of others.

Sadly, Uno suffered a heart attack on Christmas Eve in 1976 and died at the age of 47. He was not able to see the fruits of his labor with regard to the Redress Movement.

At the 1978 National JACL Convention in Salt Lake City, JACL adopted a resolution that called for redress payments of $25,000 per individual and an apology by Congress acknowledging the wrongdoing caused by EO 9066. Uno was acknowledged for his devotion and dedication to the Redress Movement.

Redress will be a topic at this year’s National Convention, once again in Salt Lake City, and Uno will be remembered for his pivotal role.

In 1985, National JACL posthumously honored Uno’s work on behalf of the organization and all Americans by establishing the Edison Uno Civil Rights Award, calling Uno “a strong and vocal advocate of human and civil rights” and “one of the first to call for the government to redress Japanese Americans for the wartime incarceration.”

Edison Uno, a true American hero.

Registration is now open for the 2019 JACL National Convention in Salt Lake City. For details, please visit the JACL website at www.jacl.org.