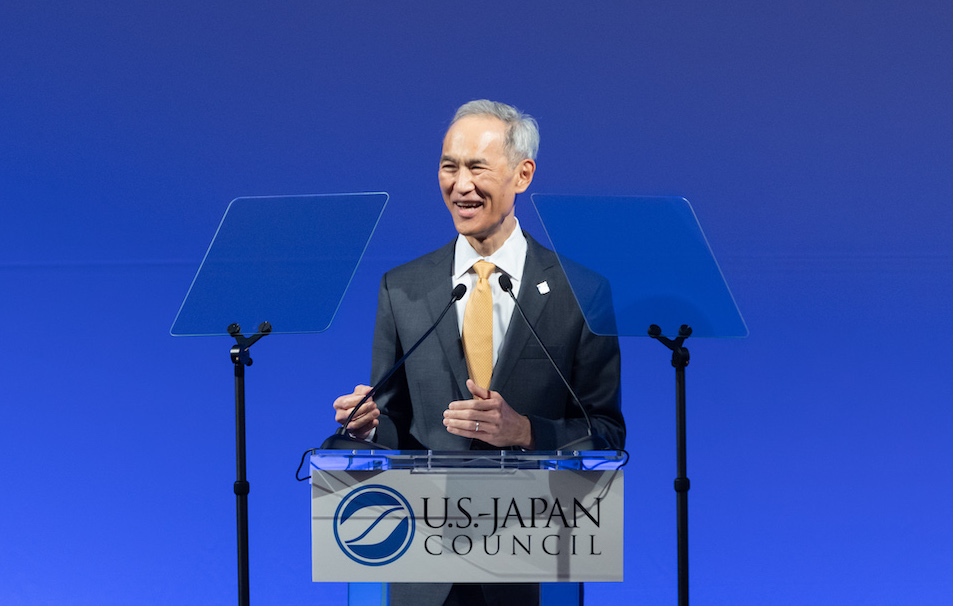

USJC Executive VP Fred Katayama addresses the audience at the 2022 conference in Tokyo. (Photo: Courtesy of Fred Katayama)

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor

(Note: This article is the result of three conversations over many months with Fred Katayama, a former TV journalist who is now executive VP of the U.S.-Japan Council. The conversations occurred before he formally began working for the USJC, a few months into the job and after the USJC conference was held in late October.)

Fred Katayama smiles for one last photo in the newsroom as a journalist before moving on to become the executive vice president of the U.S.-Japan Council. (Photo: Courtesy of Fred Katayama)

Fred Katayama’s past 10-plus months have been a time of transition and activity. On Valentine’s Day in February, the award-winning veteran broadcast journalist, whose face, name and voice became familiar to watchers of CNN and Reuters Television, left his chosen profession after nearly 40 years.

In a way, it was surprising even to Katayama himself. “I never dreamed any occupation outside of journalism. I had a single-minded, razor-sharp focus. This is the only thing I ever wanted to do from the time I was a kid,” he told the Pacific Citizen.

This former journalist’s new job? Executive VP at the U.S.-Japan Council. “It’s a whole new ballgame for me,” Katayama said, despite being a founding board member of USJC.

Indeed, because between Day 1 in his new role and Oct. 27–28, he went from learning where the men’s room was to helping with the planning and prosecution of the USJC’s first in-person conference — in Japan, no less — since pre-Covid times in 2019 in Los Angeles, the last time the USJC held an in-person conference.

If joining USJC is, as Katayama put it, his “second act,” it’s necessary to look to the time of his life before he mapped out the route he took to begin his first act of becoming a journalist: growing up in the Los Angeles suburb of Monterey Park, Calif., the eldest son of June and Hideo Katayama. His siblings were Andy, Steve and Mari, who was known as Pat to her friends when growing up.

“I was a member of Troop 145, Maryknoll Boy Scouts,” Katayama recalled of his days as a member of, as he put it, the “Maryknoll Mafia.” “I played in the CBO, the Crescent Bay Optimist. Japanese American basketball and baseball leagues. I saw Japanese Americans every day of my life because I went to Maryknoll School. That used to be a Catholic elementary school.

“Friday nights were [troop] meetings,” he continued. “And then Saturdays were my baseball/ basketball practice, depending on the season, for CBO.” Since games were on Sundays, that meant participating in Maryknoll’s Japanese American Catholic community was an everyday part of his routine.

One indelible Katayama memory of Maryknoll involves longtime Pacific Citizen staffer Harry Honda.

“He was always sitting outside on the bench after the 10 o’clock mass,” he said. That connection would be useful years later when Katayama was attending New York’s Columbia University, where he majored in East Asian languages and culture as an undergrad, followed a master’s degree in journalism.

“The reason I went into journalism was, I was very interested about the redress-reparations drive,” said Katayama. “The internment really made me interested in seeking justice. And I thought journalism was a great way to seek justice for people who were mistreated.”

That interest in journalism, his connection to Honda and timing of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians hearings in New York City converged such that he was able to cover them for the Pacific Citizen.

“I just went, wrote it and sent it to them in the mail, and they published it,” Katayama said. “And other things that I would write, I would just send it to them.” Although he “never got a dime for it,” he did get published clips with his byline, a common drive for young journalism majors.

Before he became a broadcaster, Katayama submitted many articles for the Pacific Citizen, like this article from Dec. 11, 1981.

Like many people when they are young, Katayama went through what he describes as an identity crisis. Whether it was burnout from that seven-day-a-week Maryknoll regimen, adolescent angst or a personal form of rumspringa, it happened.

“When I was a kid growing up, I had an identity crisis,” he recalled. “And I wanted nothing to do with Japan, nothing at all, or Japanese Americans, even though I went to Maryknoll school and spent seven days a week with them, even though my closest friends are still Japanese American.”

A couple of things, however, would redirect him to embrace his Japanese American and Asian American heritage. It was during college that Katayama, as he put it, “discovered Japan.” Instead of becoming economics major, he became an East Asian Studies major. That, combined with his master’s degree in journalism with a focus on business journalism would later pay off in his future career.

Before that, however, Katayama had a fateful encounter with a now-legendary local TV news anchor who not only opened his eyes to the world of a professional newsroom but also urged him to embrace his identity. That TV journalist’s name: Tritia Toyota.

Prior to that, he also remembered seeing on the local ABC affiliate something new: a Japanese American TV news anchor. His name was Ken Kashiwahara. Until then, the only other person of Japanese ancestry he had seen on TV was George Takei, aka Mr. Sulu of “Star Trek.” Hoping for a second sighting of Kashiwahara, Katayama began watching every newscast hoping “to see this guy pop up.”

“Pretty soon I got so into news, it didn’t matter whether he was on or not. I was just watching every day,” Katayama said. “CBS, NBC and ABC — all of them, but especially ABC at the time.”

Sometime later, it was a meeting with Toyota that Katayama remembers as a life-changing experience. It happened when he was a Boy Scout selling Nisei Week programs in Little Tokyo, when Toyota was a VIP in the motorcade. He ran after her car when it went up the parking structure ramp of the Kajima Building, when the Sumitomo Bank was a tenant.

“She hears these thumping footsteps and sees this little kid with programs running after her. So then, she says, ‘What do you want?’ Totally out of breath, totally out of breath, ‘Your autograph.’

“She says, ‘Oh, OK.’ Gets the car to pull over, and then she says, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ And I said, ‘I want to do your job. Do what you’re doing.’ ‘No kidding?’ ‘Yeah, I want to be a journalist.’”

Katayama remembers her questioning his sincerity, asking him if he didn’t really instead want to be a doctor, lawyer, accountant or engineer — the “usual professions” Asian American kids’ parents steered them toward. He told her, “All my life, I want to be a journalist.” Toyota told him if he ever wanted to see the newsroom to call the station, offering to give him a private tour.

“So that’s what I did. And when I went to the newsroom, I felt like a seminarian who has confirmed his calling. The energy of that newsroom — I said, ‘This is definitely what I want to do.’”

Interestingly, according to Katayama, Toyota not only transmitted the journalism bug to him, she foreshadowed her own eventual departure from the field — and may also have implanted the idea that he, too, might someday leave journalism behind.

“That time when I visited the newsroom, she told me about that. She said, ‘I’m not going to be here that long because at one point, I’m going to switch — I’m taking courses at UCLA now. I’m really into Asian American Studies. And you should think of yourself not just as a Japanese American, think of yourself as Pan Asian.’

I guess the term Asian American that Yuji Ichioka had coined was not as standardized yet. She said, ‘Think Pan Asian.’ Then a few years later, she founded that Asian American Journalists Assn. So — oh, that’s what she’s talking about.’”

As for his identity crisis problem, Katayama thanks Toyota. “She’s the one who got me out of it,” he said. And, of course, Toyota left TV news years ago for UCLA, where she is an associate researcher at the Asian American Studies Center and has served as an adjunct professor in anthropology and Asian American Studies.

❖❖❖

Katayama credits another woman for his path to the U.S.-Japan Council: Irene Hirano-Inouye, a legend in her own right, having been involved with the founding of both the Japanese American National Museum and USJC.

As a New Yorker, Katayama was already on the board of the Japan Society of New York when Hirano-Inouye sought him out. He remembers her telling him that she was “thinking about forming this organization” that would become the USJC. She asked him: “Can you help me out?” As it turned out, the concept of USJC was already something on which he was presold.

After meeting with other nonprofits to learn how they were structured, he remembers attending a meeting in 2008 where a select group of Japanese Americans worked on writing a vision statement for the nascent organization. Among those present at the meeting was Hirano-Inouye’s husband.

“I’ll never forget what Sen. Dan Inouye said that day. He said, ‘You know, when you think about it, Japanese and the Japanese American communities we live in are more or less the same cities — Honolulu, Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, Chicago, Washington, D.C., New York. But how well do we really know each other?

“‘We get together at an annual dinner, Japanese companies often pitching in with a lot of money. We shake their hands, may play in a golf tournament, then we don’t see them for another year. We don’t socialize with them. We don’t really know them. Wouldn’t it be great if we got together and got to know each other more? And together, we could also do something for U.S.-Japan relations.’ And that was for me like the lightbulb moment.”

When the USJC became an official nonprofit entity in 2009, Katayama said, “It grew much faster than any of us expected.”

“I thought, ‘Wow, it’s even bigger than I had imagined.’ … I never imagined younger people getting so engaged. I thought the more Americanized you got, as you’ve got Yonsei, Gosei, that you might forget or not be in touch with your heritage,” Katayama said.

The big difference, he believes, was that the days of Nichibei-Keizai Masatsu — Japan trade fiction — were decades in the past. “Now it’s Cool Japan. Now it’s anime. Now it’s manga. Now it’s Japanese food. So, you don’t have that resistance or that sense that, you know, you can’t defend Japan because they might think you’re not American. Now you can embrace that culture.”

❖❖❖

Just like Toyota before him, Katayama said he started thinking about life beyond journalism a few years ago. But he had questions — and stipulations. He asked himself, “Is there a way I can make a difference?” Furthermore, he knew that “whatever I do in the second act, I want it to involve Japan. And if not Japan, Asia.”

Katayama’s second act, transitioning from journalism to being in charge of development at USJC, started to come together about a year ago.

“I served on the board until my term came up,” he said. “And then when this opportunity came, at first I didn’t think about it. I knew someone had left, but then a fellow board member reached out to me and said, ‘Hey, have you thought about it?’ I didn’t even answer him right away.”

But when Katayama’s wife, Kaoriko Kuge, also a TV news journalist, told him he should consider it, he did. He had lunch with Suzanne Basalla, who he had known for years, from before she became the USJC CEO and president after Inouye-Hirano resigned from that role due to health reasons before her death in April 2020.

Regarding Basalla, Katayama said, “She’s someone I really respect. I think we had a chemistry. I felt the chemistry and the kinship in our lunch. And then we chatted some more the following week, and I just kept getting jazzed and jazzed and more jazzed and pumped up. I thought ‘Yep, for this I can leave journalism.’”

Attendees at the USJC conference, held Oct. 27-28 in Tokyo, take the opportunity to exchange business cards. (Photo: Courtesy of Fred Katayama)

Asked how his new work contrasted to what he did before, Katayama said, “I’m an executive now. I’ve got a team, as opposed to before when I was a member of a team. … Two, I’m in a nonprofit; my whole career has been in the private sector. But I think in terms of culture, one thing is dealing with a lot of meetings. But we’ve resolved some of that problem. For example, Focus Fridays, where we decided no meetings on Fridays, when we get a lot of work done. But I think if there’s a difference in terms of attitudes toward the job, I felt that for the first time, I can focus on my passion 24/7.

“Our mission is to strengthen U.S.-Japan relations on a people-to-people basis,” he continued. “I love meeting people, and I think being able to have lunches with them, doing office visits, finding about how their kids are doing, has really been a great part of my job. I really enjoy the people-to-people nature of it and seeing progress.

“Now I’m more in a quantitative world of numbers because I’m in development. How are we doing? How are we tracking against our goals? In journalism, we really didn’t do that.”

Katayama does allow, however, that when news broke of the July 8 assassination of former Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, his journalistic instincts returned to the fore.

“I dropped everything that I was doing,” he said. In a role reversal, though, he was no longer the person on camera and instead worked with the USJC’s communications manager. “My old station called me and said, ‘Hey, Fred. We heard about you at this U.S.-Japan nonprofit. … Can I interview you?’ And I said, ‘No. Thanks for your interest, but I’m not the face of the organization. Suzanne Basalla is our CEO, so she should be on camera. And I will arrange it, so she will as long as she accepts. So, we got her on my old station at KIRO, Channel 7, in Seattle. She also appeared on KING TV, Lori Matsukawa’s old station.”

❖❖❖

It’s now been almost two months since the USJC conference — the theme for which was “The Great Reconnect: Strengthening Alliances, Partnerships and Communities” — took place at the Cerulean Tower Tokyu Hotel in Tokyo.

In addition to the usual holiday season hubbub, Katayama is busy trying to meet fundraising targets before the year’s end. He is also busy now with other responsibilities, but in retrospect, pleased that the conference was a success.

“It makes me so proud and happy when you see more than 700 people gather in Tokyo, despite all those pandemic travel restrictions that were in place at the time when we announced the conference in the summer,” Katayama said.

“I think there was almost nearly a third, if not more, of the people there under the age of 40. Name any other U.S.-Japan or Japanese American organization that you know of that had a big powwow where we had that percentage of people under the age of 40. That’s a lot of momentum and energy and idealistic vibes there.

“And you see them, Japanese Americans, engaged with their Japanese counterparts, all in the name of a common goal of strengthening U.S.-Japan relations through the people-to-people level. Then you say, ‘Wow, this is all worth it.’”

It would appear that for Katayama, leaving behind what once was his life’s passion has worked out.

“It’s my life,” he said. “My wife is from Japan, my son is a dual citizen and I’m an American. And this unites all of us — a Japanese American-founded and Japanese American-led organization is now more diverse. It’s not just Japanese Americans and Japanese. It’s other Americans, too. And the board has also become more diverse. And to do this, to turn my passion into my profession — my passion was my profession. I’m really lucky. Journalism, that’s all I ever dreamed of. But along the way, in college, I discovered Japan, and now I’m able to turn this passion into my second act.”

Fred Katayama (far right) poses for a group photo with other attendees at the Oct. 27–28 USJC conference in Tokyo. (Photo: Courtesy of Fred Katayama)