Chol Soo Lee, center, is the subject of “Free Chol Soo Lee,” a documentary directed by Julie Ha and Eugene Yi about the tragedy, triumph and tragedy of the Korean immigrant whose miscarriage of justice spawned a pan-Asian American movement to free him from prison.

A new documentary shines light on an important, still-unrecognized saga.

By George Toshio Johnston, Senior Editor, Digital & Social Media

All the King’s Horses

And All the King’s Men

Couldn’t Put Humpty Together Again

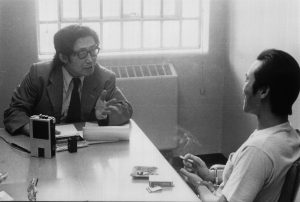

Investigative journalist K.W. Lee, left, interviews Chol Soo Lee in prison.

Of the hundreds of articles investigative journalist K.W. Lee would write about his fellow Korean immigrant who was imprisoned for a murder he did not commit, it began with one headlined “Alice in Chinatown Murder Case.”

The allusion to Lewis Carroll’s whimsical “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” turned out to be apropos and prescient. Now 93, Lee’s decade’s old reporting would be an odyssey down a confounding rabbit hole that haunts him to this day.

For the man whom the warhorse reporter helped free from prison, however, the aforementioned nursery rhyme wasn’t whimsy. Despite the tireless efforts of one journalist and a diverse army of Asian Americans brought together by a “there but for the grace of God go I” realization to fight the outrageous injustice visited upon him, nothing on Earth could quite rebuild the broken life of one Chol Soo Lee.

That epic story is revisited in the documentary “Free Chol Soo Lee.”

Future Awards Contender?

For first-time directors Julie Ha and Eugene Yi, January 2022 will be looked back upon as a turning point in their own respective journalism careers. After six years of work, their documentary not only premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in its U.S. Documentary Competition Selection, but also within days, it was acquired by the streaming service MUBI.

Already destined to be shown nationally on PBS, the acquisition means “Free Chol Soo Lee” will likely be screened theatrically for Academy Award consideration for next year’s Oscars.

After seeing it, TV reporter-turned-communications professor Sandra Gin told Ha and Yi, “This ain’t just buzzworthy, it is Oscar-worthy.” Gin has some insights regarding such matters.

Sandra Gin, Chol Soo Lee and Tom Nakashima met in 1983 for the premiere of the episode of KCRA’s “Perceptions,” titled “A Question of Justice.” (Photo: Courtesy of Sandra Gin)

One of her many Emmys came in 1984 for an installment of the Sacramento-area public affairs program “Perceptions” titled “A Question of Justice,” which covered the same subject matter, in the Historical, Cultural and Religious category.

Attorney Dan Mayeda, associate director of the UCLA School of Law’s Documentary Film Legal Clinic — which helps documentarians with pro bono legal services such as helping set up LLCs, drafting contracts, navigating the fair use doctrine and more — called the finished product “a magnificent documentary.” (Ha and Yi were among the Clinic’s first clients.)

Nick Allen of RogerEbert.com, meantime, wrote that “FCSL” was “extraordinarily moving” and “the best documentary I’ve seen from this year’s U.S. Documentary competition.” (For the record, the movie that won in that category at Sundance was “The Exiles.”)

Unknown No More

Although the praise for “FCSL” is deserved, the story told in the movie never quite became as embedded in the greater collective consciousness the way other tragic miscarriages that affected Asian Americans did.

A case in point: Su Kim, who is one of “FCSL’s” producers and the 2022 Amazon Studios Producers Award for Nonfiction recipient for “Free Chol Soo Lee” at this year’s Sundance.

From left: “Free Chol Soo Lee” directors Julie Ha and Eugene Yi, and producer Su Kim

Prior to her vital involvement with “FCSL,” Kim admitted she had never heard about Chol Soo Lee.

“I felt really upset that I didn’t actually know about this story at all. I grew up on the East Coast. I’m in my 40s. And I had never ever heard of this story. The more I heard about the story, the more I realized that it would be a true tragedy to have it buried in history,” Kim told the Pacific Citizen.

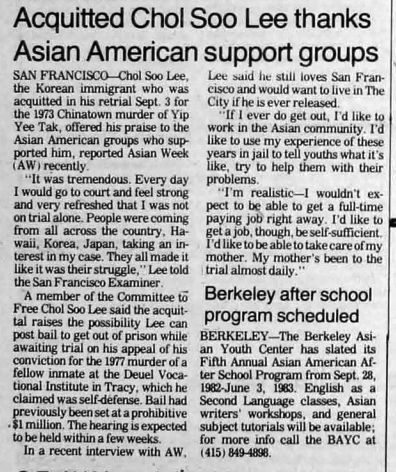

P.C’.s Chol Soo Lee news coverage from Sept. 24, 1982

Ha concurred, saying, “This is a landmark movement of Asian Americans. They overturned two murder convictions to free this Korean man from death row. And it was like, why is this story not known? … I sensed he (K.W. Lee) was so worried that it was just going to get buried in history, and people wouldn’t know about it.”

“Free Chol Soo Lee” may finally remedy that situation. Still, for those understandably unfamiliar with the saga, the documentary fills in many of the details of how Chol Soo Lee was, at age 20, charged, tried, convicted and imprisoned for a brazen gang-related slaying in San Francisco’s Chinatown in the early 1970s. It was “merely” the latest murder among many in a turf battle between rival Chinese gangs.

On June 19, 1974, Chol Soo Lee was convicted of first-degree murder. His sentence: life imprisonment. But that wasn’t the worst of what was in store for him.

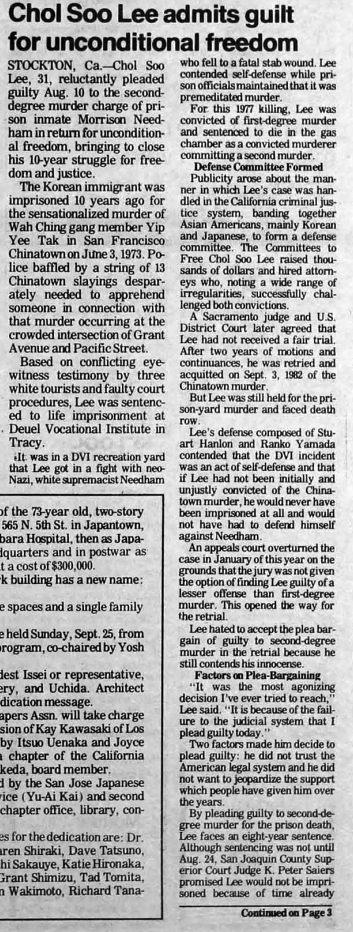

While incarcerated at Deuel Vocational Institute in Tracy, Calif., he actually did kill a fellow inmate, Morrison Needham, said to have been a member of the Aryan Brotherhood, in a what Chol Soo Lee claimed was an act of self-defense.

That incident would put him on the path to Death Row at San Quentin State Prison.

Dangerous Naiveté

Although he freely admitted to being a “street punk” with some petty criminal offenses on his rap sheet, Chol Soo Lee had nothing to do with the June 3, 1973, murder of Yip Yee Tak. He naively believed that the American legal system would soon realize they had the “wrong guy” and send him along his merry, wayward way.

Although he had some street smarts, Chol Soo Lee was in for a rude awakening. It was as if the city’s political, law enforcement and legal establishment, driven by the need for an expedient and tidy solution to show they had established control over the gang war (and thus continue the flow of tourism dollars), had conspired to live up to the brutal paean to official indifference uttered at the end of 1974’s “Chinatown.”

It must have seemed that Chol Soo Lee, with his criminal record and having been singled out from a police lineup, was a gift from the gods of neglect. That he was Korean, spoke no Chinese, wasn’t a gang member and didn’t commit the crime mattered not. Neither did the ballistics test that disproved the handgun accidentally fired by Chol Soo Lee days before the slaying was the same one used in the murder, nor a conveniently overlooked key eyewitness who would later testify that Chol Soo looked nothing like the man he saw commit the crime.

“Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”

The Rest of the Story

But that malfeasance is just one of the threads found in “Free Chol Soo Lee.” K.W. Lee’s investigative reporting was another vital one.

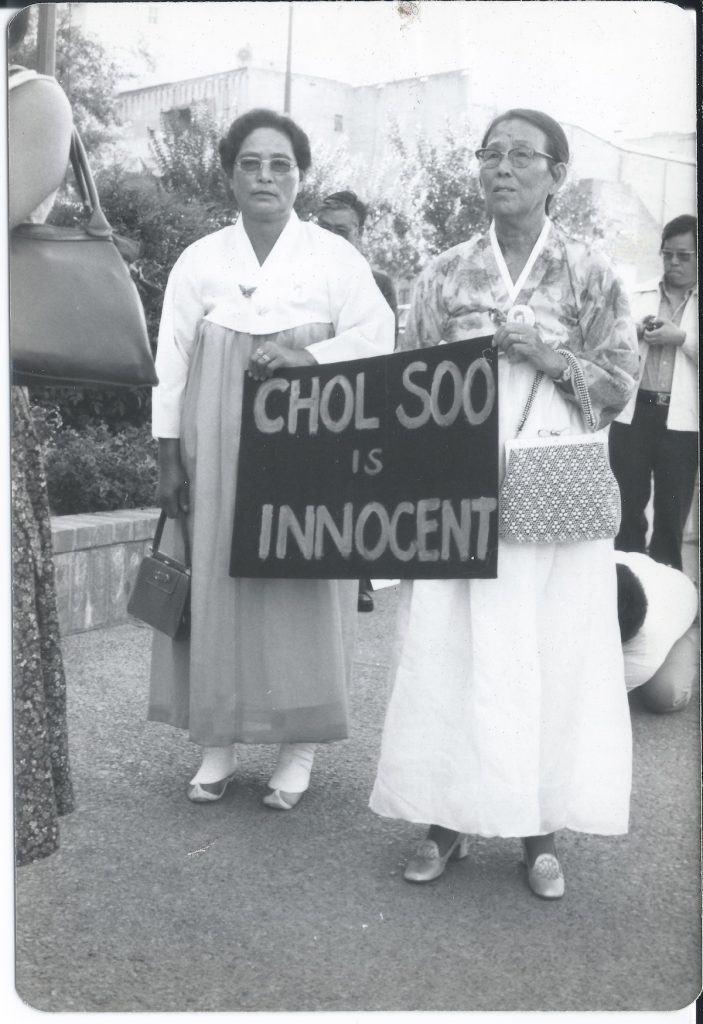

Although initially hesitant to support the bid to free Chol Soo Lee from prison, according to K.W. Lee, the immigrant Korean community would eventually come on strong to seek justice for him.

The other thread Ha and Yi wove in was that of the many Japanese Americans such as Jeff Adachi, Warren Furutani, David Kakishiba, Jeff Mori, Peggy Saika and Mike Suzuki, along with Chinese Americans Art Chen, Chris Chow, Grant Din, Esther Leong, Susan Lew and Derrick Lim who came forward to raise awareness of the injustice that the justice system had imposed upon Chol Soo Lee.

Many among the aforementioned would go on to dedicate their lives to become lawyers or public servants to ensure there were no thumbs on the scales of justice.

In K.W. Lee’s eyes and in Chol Soo Lee’s words, though, there was one particular true believer, one person above the others who took action after reading the initial newspaper reports implicating Chol Soo for the murder. Her name: Ranko Yamada, and she is one of “Free Chol Soo Lee’s” treasures, thanks to her participation in telling the tale.

Interestingly, according to K.W. Lee, many of Chol Soo Lee’s fellow Korean immigrants, inculcated by Confucian respect for authority figures, initially wanted nothing to do with him. Why, after all, would the police arrest someone if he wasn’t guilty?

“Free Chol Soo Lee,” however, shows Koreans — including Chol Soo Lee’s mother — eventually joining the Free Chol Soo movement with a fierceness in what would become the first pan-Asian American community movement that had real-world results. It’s that storyline that is at the heart of “Free Chol Soo Lee.”

Journalism to Documentaries

For Ha, her knowledge of the Chol Soo Lee story resulted from her own background and journalism career that included working for UCLA’s student-run publication Pacific Ties, as well as Rafu Shimpo and KoreAm Journal, now defunct.

P.C’.s Chol Soo Lee news coverage from Sept. 2, 1983

“I’ve known K.W. for more than 30 years. I met him when I was 18 years old. He inspired me to become a journalist. So, I’ve known about the case for a long time. Eugene has actually known about the case for a long time through K.W. But I never thought about making a film,” Ha told the Pacific Citizen.

Ha actually wanted to write about Chol Soo Lee, perhaps as an in-depth magazine feature. But after attending the funeral for Chol Soo Lee, who died on Dec. 2, 2014, at age 62, the feeling that “was something just even beyond grief” from that day would lead her down a different path: documentarian.

Yi’s path, meantime, went from studying neuroscience in college to video editing and journalism, which would lead him to KoreAm Journal, where he met editor-in-chief Ha.

Regarding his directing partner’s journalism chops, Yi said, “I always appreciated working with her. She was an incredible editor, just so giving and so supportive in terms of all the crazy story ideas that I might have or how many words over the limit I might have been. It was always just incredible working with her. And she always seemed to be able to bring out the best from whatever project I was working on.”

When KoreAm Journal ceased publication, Ha and Yi decided it was time to focus on telling Chol Soo Lee’s story. “It literally felt like it was beckoning us to tell it,” Ha said.

With Yi’s experience in video editing and their knowledge of the existing archival materials, including K.W. Lee’s audiotapes, Chol Soo Lee’s memoir and more, the documentary route beckoned.

Fortuitous Circumstances

Although the path to completing the documentary was long and far from easy, there were several fortuitous stops along the way.

One was the 2018 formation of the Documentary Film Legal Clinic at UCLA’s School of Law. At its outset, Mayeda said they really didn’t have any clients, a situation that is completely different now that the word about it has gotten around.

“I had known Julie from just casually from when she was at the Rafu,” Mayeda recalled. “I ran into her somewhere, and she mentioned she was working on this documentary about Chol Soo Lee. I said, ‘You’ve got to bring that to the clinic, it would be great to work on that. … They were one of our first clinic clients.”

Ha concurred. “They helped us tremendously,” she said. “You know how much legal services can cost. … When you’re an independent film, you’re just struggling to balance all these expenses that you had. So, it saved us a tremendous amount of money.”

Connecting with Su Kim and her producing partners, Jean Tsien and Sona Jo, was also key for Ha and Yi.

“I’m Korean American, and it really pissed me off that this had happened,” Kim said. “And it was very resonant to many of the experiences, I think, that we all have, a lot of Asian Americans have had. I make films, and this is what I know how to do. So, I said, ‘Well, OK, I’ll help you guys out. Let’s see what we can do.’ And so that’s how I got involved.”

Voices of Authority

It was Kim, for instance, who helped bring in Sebastian Yoon, who gave voice to words written by Chol Soo Lee in his memoir. She had heard about Yoon speak at an Open Society Foundations Q&A, not realizing that he had actually appeared in the documentary “College Behind Bars.”

As it turned out, Yoon’s own life experience had many parallels to that of Chol Soo Lee, such that he could relate to much of what Chol Soo Lee had experienced.

But Yoon had something that Chol Soo Lee did not — an opportunity to attend college while in prison.

“He received his degree while in incarcerated,” Kim said. “And he was incredibly moving. He really spoke from the heart. And I just really felt immediately, like, this guy can represent the voice of Chol Soo.”

Gathered on Feb. 22, 2006, at the Chol Soo Lee Symposium at UC Davis are (from left) Tom Nakashima and Sandra Gin, who won Emmys for producing an episode of the public affairs program “Perceptions” on the Chol Soo Lee case, titled “A Question of Justice”; Chol Soo Lee; K.W. Lee; and Derrick Lim. (Photo: Courtesy of Sandra Gin)

Yi, meantime, also credited TV reporter Sandra Gin. “Without her work,” he said, “we wouldn’t really have a film.” For her part, Gin, too, recognized the import of what Yoon brought and how that helped them in their filmmaking process.

“He narrowed down the focus for them. And that’s what really transcended and transformed the trajectory,” Gin said.

Different Direction?

On the topic of trajectories, could the kudos conveyed toward Ha and Yi for “Free Chol Soo Lee” point them in a new direction from the written-word world of print journalism? It may be too soon to say for Ha.

“We were thrilled and honored when we got invited to show the film at Sundance,” she said, calling it a “six-year labor of love.”

“And, it’s not lost on us that the movement to free Chol Soo also took six years. We’re just so excited to share this story with the world.”

But does this augur a possible career change?

“I’ll never say never because I have spent six years trying to build my skill set. But at the same time, I’ve always felt like I needed to work on this one film, on this one story. I literally felt like, I had to do it. I could not not do it. So, I’m thrilled that it’s finished,” Ha said, adding that “My first love is journalism and writing.”

Yi, however, said that filmmaking and writing have “really been twin loves for me.”

The Legacy of Chol Soo Lee

Despite the success and victory celebrated by the Free Chol Soo Lee movement that made him a free man after 10 years in prison and an escape from death row, the documentary shows that for Chol Soo Lee the man, the happiness and afterglow were short-lived.

Jeff Adachi

What began as the “Alice in Chinatown Murder Case” had a downbeat ending that, ironically, was similar to the one in “Chinatown,” one of the rare studio movies with a nihilistic ending that defied the happy Hollywood ending trope.

In the end, the traumas endured and the pains suffered by Chol Soo Lee were too much for any human to survive.

At the end of the credit roll for “Free Chol Soo Lee,” Ha and Yi added an “In Memory” dedication to Jeff Adachi, who died in 2019. He had served as San Francisco’s public defender, doubtless inspired by his involvement, when he was still a young man, baby, in the Free Chol Soo Lee movement.

It’s appropriate, then, that Adachi gets the last word, his perspective on the meaning and heartbreak of Chol Soo Lee’s legacy, spoken at his 2014 funeral.

“Chol Soo ended up doing more for us than we did for him.”

Speaking the Truth

Not only was Ranko Yamada a vital part of the original drive to free Chol Soo Lee, she is a major figure in the documentary “Free Chol Soo Lee.” Yamada was kind enough to answer a few questions via email for the Pacific Citizen.

Pacific Citizen: With your first-hand experience as a community activist — arguably the original/most important person to speak out and reach out regarding the injustice that was inflicted upon Chol Soo Lee — what was your overall reaction to seeing the completed, final-cut version of “Free Chol Soo Lee”?

Ranko Yamada: My overall reaction is a resounding “Wow.” Choosing to focus on Chol Soo Lee sounds so obvious. It was anything but obvious. There were so many layers and dimensions in Chol Soo the person, the immigrant, his cases, the coming together of support from the Korean, pan-Asian and progressive communities, endless issues and exceptional people like K.W. Lee. The film didn’t compromise. It wasn’t sanitized. The story came through clean and truthful. The filmmakers, Julie Ha and Eugene Yi, perceived the whole with a deep regard and respect for Chol Soo and all of the players. Great job; great film.

Ranko Yamada, right, meets with journalist K.W. Lee on June 8, 2018, in Los Angeles. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

P.C.: Was there any element that the filmmakers did not include or address?

Yamada: Not really. There was so much critical information packed into 83 minutes. Of course, there are hundreds of side stories and anecdotes that couldn’t be included, but everything essential was there.

P.C.: The pan-Asian American movement to free Chol Soo Lee included many Japanese Americans. Presuming that they were offspring (or were knowledgeable) of Japanese Americans unjustly incarcerated by the federal government during World War II because of Executive Order 9066, how much do you think that this was explicitly or implicitly a recognition that Lee was the victim of unfair treatment by the political/law enforcement establishment of San Francisco and a motivation to help get him the freedom he deserved? If you believe that there was this recognition by JAs to help Lee for that reason, can you elaborate on this topic?

Yamada: I really don’t know how much identity there was in the support for Chol Soo Lee with the incarceration of JAs during WWII. The grass-roots movement for redress was developing at the same time. Many of us were involved with both issues, but I don’t believe it was a defining relationship. We talked about institutional and individual racism, about oppression in our society.

We also talked about uniting with all people’s struggles. Personally, Chol Soo reminded me of my dad — not because my dad was incarcerated at Rohwer, but because he was Kibei Nisei who returned to the U.S. at 17 and never had a chance to go to school or learn English.

P.C.: Despite the legal victory/victories that saw Lee win his freedom, it’s clear from the documentary that he was nevertheless still haunted by the traumas he endured, which made it difficult to reintegrate into the “straight and narrow life” once he was free and thus put him on a path that included drug abuse and crime and, ultimately, his tragic disfiguration from the attempted arson.

In other words, if Chol Soo was unable to save himself from himself, in retrospect, what are the lessons from the Chol Soo Lee saga we can apply to the future when someone gets a second chance, whether the problem was drugs, crime, gangs, homelessness, etc.?

Yamada: This is complicated. Yes, I think he was haunted by past traumas. More so, the things he didn’t get in early life, like basic opportunities of education and a stable supportive family, can surely restrict the quality of life when at 30 you have no skill sets, no money and no real home.

Lessons? Chol Soo had about 30 years as a freed man before he died. He had grief, traumas, sadness and all the rest. His life was tragic. I don’t think he ever doubted that being outside was way better than being in. The lessons are still the same. The best chance of survival and a better society is to support each other. Do what you can when you can — and keep your eyes wide open.