The stone memorial (Photos: Courtesy of Dan Mayeda)

A JACLer traces the path of his ‘enemy alien’ grandfather.

By Dan Mayeda

Like many other Nisei, my dad, Ray Mayeda, was somewhat reluctant to talk much about his incarceration experience in one of the Poston, Ariz., camps. But especially after he received an official apology from the government as part of the redress campaign, Ray Mayeda began to share and voice a bit more about his father (my grandfather), Kunitomo Mayeda.

Dan Mayeda stands next to the Santa Fe Internment Camp Remembrance Site stone memorial during the JACL’s pilgrimage to the site in July as the final-day activity of the organization’s National Convention.

Kunitomo came to America in 1907 as a 16-year-old teen. Imagine the courage it must have taken at that age to travel to a far-away country where you didn’t know anyone or speak the language well. He ended up in San Diego, where he first worked as a houseboy and then a cook at the world-famous Hotel del Coronado. Ultimately, he leased some land, plowed fields and built a successful celery farm business.

On a trip back to Japan, Kunitomo got married. He brought his wife to America and started raising a family. First came Al, then my dad, Ray, then three more children. But in the 1930s, in the midst of the Great Depression, my grandmother died.

Kunitomo could not make a living while trying on his own to raise five young children, so (except for the eldest, Al) he took the family back to Japan. Kunitomo remarried there but quickly returned to Coronado to work as a gardener, so that he could send money back to Japan. After a few years, Ray rejoined his father, and he and Al enjoyed being students at Coronado High School.

Then came the Pearl Harbor attack on Dec. 7, 1941, and the whole world shattered for the Mayeda family.

Al immediately enlisted in the U.S. Army. The FBI came to interrogate Kunitomo. An informant initially alleged that Kunitomo shined a spotlight on a water tower after curfew but later admitted it was only a brief flashlight shine that had come from the general direction of Kunitomo’s house.

The FBI ignored evidence from a retired Army officer that Kunitomo was a better American than most native-born men. But, like other Issei, Kunitomo was not allowed to become an American citizen. So, before President Franklin D. Rosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of all Japanese Americans from the West Coast, Kunitomo was deemed an “enemy alien” and taken away by the FBI based on the Alien Enemies Act while Ray was at school. That left Ray literally “home alone.”

Ray did not know where his father had been taken. He told me only that Kunitomo was incarcerated in Santa Fe, N.M. I eventually learned that Kunitomo’s path went from his home in Coronado to a San Diego County jail, to brief stints in the Terminal Island and Tuna Canyon Detention Stations, both in the Los Angeles area. From there, Kunitomo eventually was incarcerated in a Santa Fe Department of Justice internment camp, along with other Issei.

I also know that Ray had to stay with old bachelors in Poston since his only family in the U.S. was either in the Army (Al) or incarcerated in Santa Fe (Kunitomo). So, the first chance he got, Ray seized the opportunity, sponsored by the Friends/Quakers, to leave camp and go live in Chicago.

Ray took a train from Poston to Chicago by way of Santa Fe. There, he was reunited with Kunitomo for the first time in two years. After the war was over, Kunitomo was repatriated to Japan at his request. That was the only realistic option since the U.S. government had stripped him of all rights and incarcerated him without a genuine hearing let alone evidence against him. Plus, his second wife and remaining children were still in Japan.

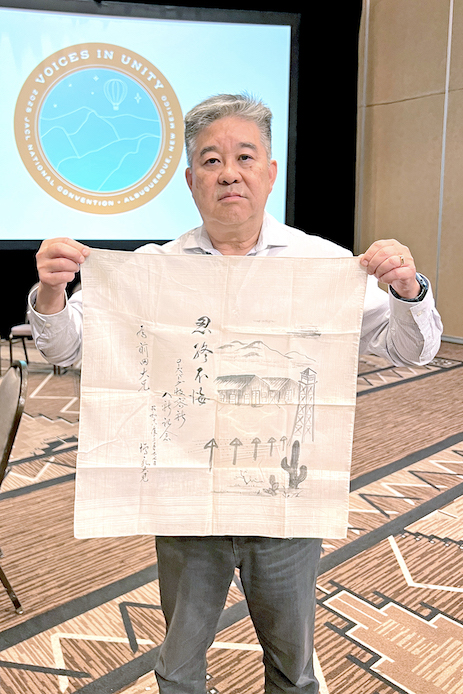

That is all I thought I knew about Kunitomo’s life in America — except for one thing. Reviewing my dad’s possessions after he passed, I found a neatly folded handkerchief on which an amateur artist had painted a scene of barracks, barbed wire, a watch tower and cacti, along with an inscription in Japanese.

At July’s JACL National Convention, Dan Mayeda holds up the handkerchief painted by Santa Fe incarceree Masunaga that he found belonging to his grandfather, Kunitomo. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

The words translate roughly as follows:

Upon entry to Camp Lordsburg: This is evidence that we were held there, a place where we experienced bad feelings. But, it couldn’t be helped. Gaman [Japanese word roughly translated: enduring hardship but also maintaining composure and grace in the face of adversity]. We had to obey. [Signed, Masunaga].

At first, I was puzzled. I had never heard of Camp Lordsburg. But after looking it up and finding a photograph of it, I realized that it was located in New Mexico, and I figured out that it was my grandfather, not my dad, who was incarcerated there.

An image from the Ireicho project confirms that Kunitomo was incarcerated at both Santa Fe and Lordsburg. Putting these pieces together, I have concluded that on March 17 or 27, probably in 1943, a fellow incarceree named Masunaga presented to Kunitomo this hand-drawn artwork. My grandfather then passed this memento down to my dad. And now I have it. (I would, however, be thrilled to give this memento to any descendant of the artist Masunaga who happens to read this!)

So, when I saw that the JACL was holding its annual convention in Albuquerque, N.M., in July 2025, I became determined to attend to see what else I could learn about Kunitomo’s journey. I wanted to attend a presentation on the Alien Enemies Act. (Kunitomo’s story is featured in an amicus brief that JACL filed in litigation challenging the Trump administration’s invocation of that act to justify the deportation of Venezuelan Americans whom it accused of being members of a criminal gang.)

The convention also included a session in which a fascinating documentary entitled “Community in Conflict” by director Claudia Katayanagi was screened about the tensions that arose when the city of Santa Fe proposed to install a historical marker at the site of the Santa Fe Internment Camp.

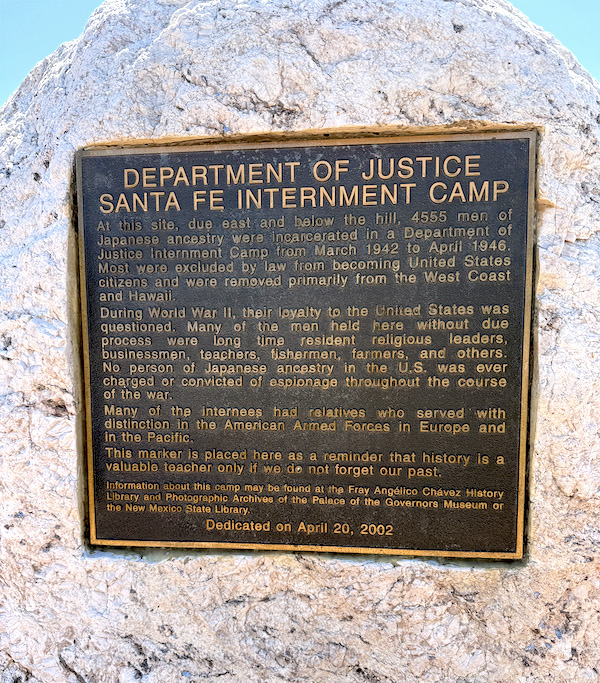

There was another session providing further history and background on both the Santa Fe and Lordsburg Internment Camps. Finally, on the morning after the convention’s Sayonara Banquet, there was a pilgrimage, organized by the New Mexico chapter’s Victor Yamada and Nikki Nojima Louis, to the site of the Santa Fe Internment Camp historical marker, which is located at the top of a hill at the Frank S. Ortiz dog park in the Casa Solana neighborhood. It was dedicated on April 20, 2002.

Visiting the site of the Santa Fe historical marker was a moving experience. The actual camp site has long been paved over with housing developments, but the marker, embedded onto a massive rock, sits on a higher point overlooking the site. The marker states in part: “At this site, . . . below the hill, 4,555 men of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated in a Department of Justice Internment Camp from March 1942 to April 1946. Most were excluded by law from becoming United States citizens. . . .”

A close-up image of the marker’s inscription at the Santa Fe Internment Camp Remembrance Site memorial

Standing there, I tried to imagine how Kunitomo must have felt to be incarcerated there along with other Issei men, all held for the crime of simply being from Japan — without any evidence of disloyalty to America.

Pilgrims left flowers to honor their friends and relatives who were forcibly incarcerated in New Mexico during World War II.

“During World War II, their loyalty to the United States was questioned. . . . No person of Japanese ancestry in the U.S. was ever charged or convicted of espionage throughout the course of the war.”

I also tried to picture the scene when my dad was finally able to leave the confines of Poston en route to Chicago, but stopped first to visit his father still imprisoned in Santa Fe. It is heartbreaking to think of my grandfather, seeing his son for the first time in years, but unable to be with him; or my dad, living without his parents at a crucial time in his young adult life, having to leave his father behind bars so that he could try to start a new life in an unfamiliar city, alone once again.

Pilgrims and descendants of those imprisoned at the Santa Fe Internment Camp gather at the memorial to share stories during the JACL’s pilgrimage to the site in July. Photos: Courtesy of Dan Mayeda

Those JACL Convention attendees who joined me at the Santa Fe pilgrimage also paid homage to their ancestors, and some read poignant bits of poetry that had been written by the incarcerees.

We did this all to remember the past and recommit to fight for justice in the present and future. “This marker is placed here as a reminder that history is a valuable teacher only if we do not forget the past.”