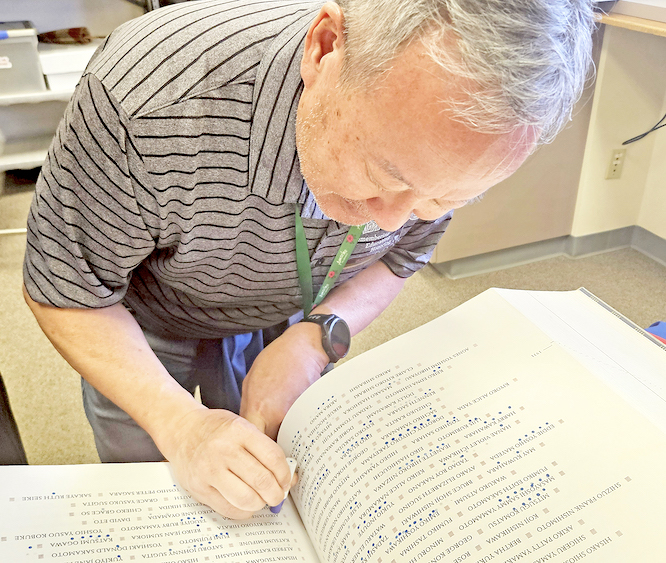

Derek Okubo of Denver stamps the Ireichō book. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

The pilgrimage is made more poignant with the Ireichō book on tour.

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

The annual pilgrimage to Amache, the Colorado concentration camp, was held May 16-18, with the official ceremony held on May 17 and a visit to the nearby Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site on May 18. But the weekend memorial event began on May 16 with some attendees stamping the Ireichō book of names. They may have been survivors of the wartime camps, or descendants or relatives or even friends of incarcerees. They were there to pay tribute to the more than 125,000 people who were imprisoned during World War II, in 75 sites from Alaska to Hawaii and California to Arkansas.

Amache, located in southeast Colorado, has held pilgrimages since 1975, making this year the 50th gathering of people from throughout the country. The Ireichō book added a poignancy to the weekend because many of those who made reservations online to stamp next to their family members’ names did so because those people were incarcerated at Amache.

The stamping began even before the actual pilgrimage because the book was brought to the History Colorado Center, a state museum in downtown Denver, for several days before the Amache pilgrimage. According to Karen Kano, a project specialist with the Japanese American National Museum who is touring with the Ireichō book across the country for camp pilgrimages and other major cities, about 200 people made reservations at both History Colorado and at the town of Granada, Colo., where the stamping was held in a room at the Amache Museum. During its three days there, 650 names were stamped in Denver, and on Friday and Saturday, 575 names were stamped.

The Amache Museum in Granada, Colo. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

On May 17, before the stamping was set up at the Amache Museum in Granada outside of the concentration camp, the Ireichō book was brought to the memorial service at the cemetery in Amache, where both Buddhist and Christian prayers were given.

Rev. Diana Thompson represented the Tri-State Denver Buddhist Temple, and Rev. Brian Lee represented Simpson United Methodist Church in the Denver suburb of Arvada.

Duncan Ryuken Williams, a Buddhist priest, introduced the Ireichō book. He’s a professor of American studies and ethnicity and religion at the University of Southern California and director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture. He also is the driving force behind the book of names and its related projects, the Ireizo online database of all the names of incarcerees searchable by name, birth year or camp, as well as Ireihi, a monument with lights that is being planned. Also on hand was the Ireichō project’s creative director, Sunyoung Lee, who suggested to Williams that putting names in a book would make a powerful statement.

The Ireichō book on display at the Amache Pilgrimage memorial service (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

Williams kicked off the memorial service by acknowledging the Amache attendees, as well as those who had died at Amache. He then invited people up to stamp the open book at the front of the ceremony.

“We are gathered here today at the Amache Cemetery, where right before the camp closed in 1945, Rev. Masahiko Wada, a Baptist pastor, helped to build the ireito here in this cemetery,” Williams said. “Ireito means a tower to console the spirits, and at that time, a wooden board, which doesn’t exist at this location anymore, mentioned all of the names of those who passed away here at Amache who were buried here at the cemetery and others who were not buried here but taken in their urns as people left the camps to go back home.

“On this occasion,” he continued, “we have an opportunity to recite the names of the 150 individuals who passed away here. I have asked the clergy to help me recite those names, and I’ve asked six camp survivors to come up and stamp representative names of those who passed away here.”

The ceremony brought a renewed awareness of the legacy of pain and the gravity of the pilgrimage to the memorial service.

A guard tower at Amache (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

That emotional depth was present all week, both in Denver and in Granada, the small town next to Amache. At the Granada School, which goes from grade school through high school, are students of the Amache Preservation Society and their longtime teacher — who’s retiring and leaving the society to a capable former student who’s also now a teacher at the school.

The school hosted a lively community-based potluck luncheon after the memorial service at the cemetery on May 16, followed by an evening program of speakers and a post-luncheon presentation on May 17, which included the National Park Service rangers and staff who conduct educational tours and programs at both Amache and Sand Creek. Amache was officially made a National Historic Site in 2024.

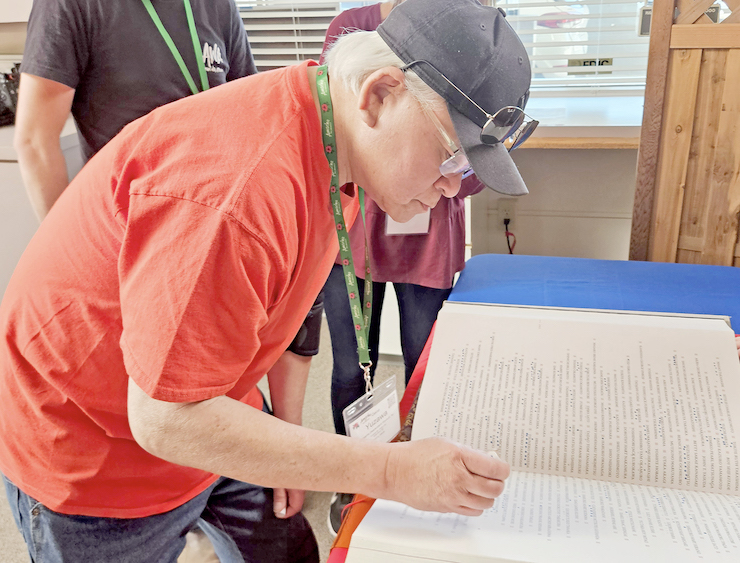

But the “star” of this year’s pilgrimage, as it will no doubt be when it travels to other sites for their pilgrimages, was the Ireichō book. Families from as far as New Jersey and as close as Denver or Albuquerque, N.M., made the pilgrimage to stamp the book. Many of the travelers were at Amache for the first time, seeing where their parents or grandparents had spent the war years and exploring the foundations and seeing the reconstructed guard tower and barracks.

The stamping seems like it would be a perfunctory act, but for many, it was a moving, emotional way to connect with an ancestor. The book is a living monument, one that can accommodate new names as people realize someone didn’t get included, or corrections made if government records misspelled a name or had an incorrect birthdate. People can go to the Ireizo website and submit corrections and additions.

Williams credits Sunyoung Lee with the idea of the book, instead of permanently etching names on, say, a stone monument.

“What are we in terms of a display strategy? We didn’t want to keep this as a database or just like a phone book,” Williams said. “How do we make sure it is a real memorial of survival as much as what happened? I think that was a very important part of the idea that this is a project that’s not just about a monument to the past, but we’re also building a monument in the present moment with the public at large, that their involvement would actually make it actually come alive with the act of stamping. She was the person that came up with the idea of the book.”

Lee has experience as a book publisher, so the concept came naturally to her.

“Names on a typical monument, engraved on stone, are not erasable,” Lee said. “I’m intimately involved with books. And one of the things that was really profound to me was this idea that the whole point of the incarceration was to try to usurp and erase this entire community. The ultimate goal of this project is also to have (multiple) books that will be available for the public, particularly for the family members of people who were incarcerated.”

The stamp is a way for people to interact with their family members.

Gene Yuzawa of New Jersey stamps the Ireichō book at the Amache Museum. (Photo: Gil Asakawa)

“That’s when we came up with the idea of making the stamps right, so there’s a way that people can show that they, themselves, have been there,” said Lee. “It’s kind of like the stones that people will leave at a gravestone, but here you have a stamp, and then in the process of doing that, they, too, become part of the project. The project is not just about the people, it’s about the interaction.”

It’s also an intimate interaction because people are allowed into the room to stamp their list of names by themselves or with family members who are also there to stamp the names. “You realize that there’s a real intimacy,” Lee said. “Because, you know, one person is looking at a book at a time, it’s almost like you have a moment to really commune with it. It’s not a public spectacle. It is your relationship with the book, your relative’s name, somebody’s family. In this world, we don’t have that much opportunity to take the time and the space to reflect on the people we’ve lost. From the very start, taking the book across the country was part of the project. It wasn’t just going to sit at JANM (in Los Angeles) and then be enshrined.

“I would say that there is a way in which the book is constantly changing and evolving, as is our project,” Lee concluded.

The Ireichō Project is scheduled to continue touring and will be at Minidoka, Idaho, July 11-13; Heart Mountain, Wyo., July 24-26; Fort Lincoln, N.D., Sept. 5-7; Crystal City, Texas, Oct. 10-12.; New York City, Oct. 20-21; and on to Poston and Gila City, Ariz., Chicago and elsewhere. To see the schedule, visit https://www.janm.org/exhibits/ireicho/venues.

This article was made possible by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL Redress Strategist Grant Ujifusa.