According to the company’s website, the origins of the Ajinomoto Group lie in this ideal: “Eat Well, Live Well.”

With Aji-No-Moto’s help, the umami flavor enhancer

is on the rise again and gaining favor in popularity.

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

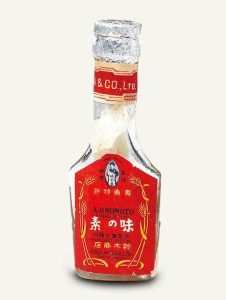

The instantly recognizable red shaker top Ajinomoto bottle

For Japanese Americans of a certain age (boomers), there was an ubiquitous presence on our kitchen tables growing up: Alongside the salt and pepper shakers and, of course, shoyu (in the iconic Kikkoman hourglass-shaped bottles), there was also the short glass jar with the red shaker top of crystals, Aji-No-Moto. Monosodium glutamate. MSG.

You’d be hard-pressed to find Aji-No-Moto at the family table today or at Japanese restaurants. That’s because MSG was struck a terrible reputational hit more than 50 years ago — and it’s still recovering from its repercussions.

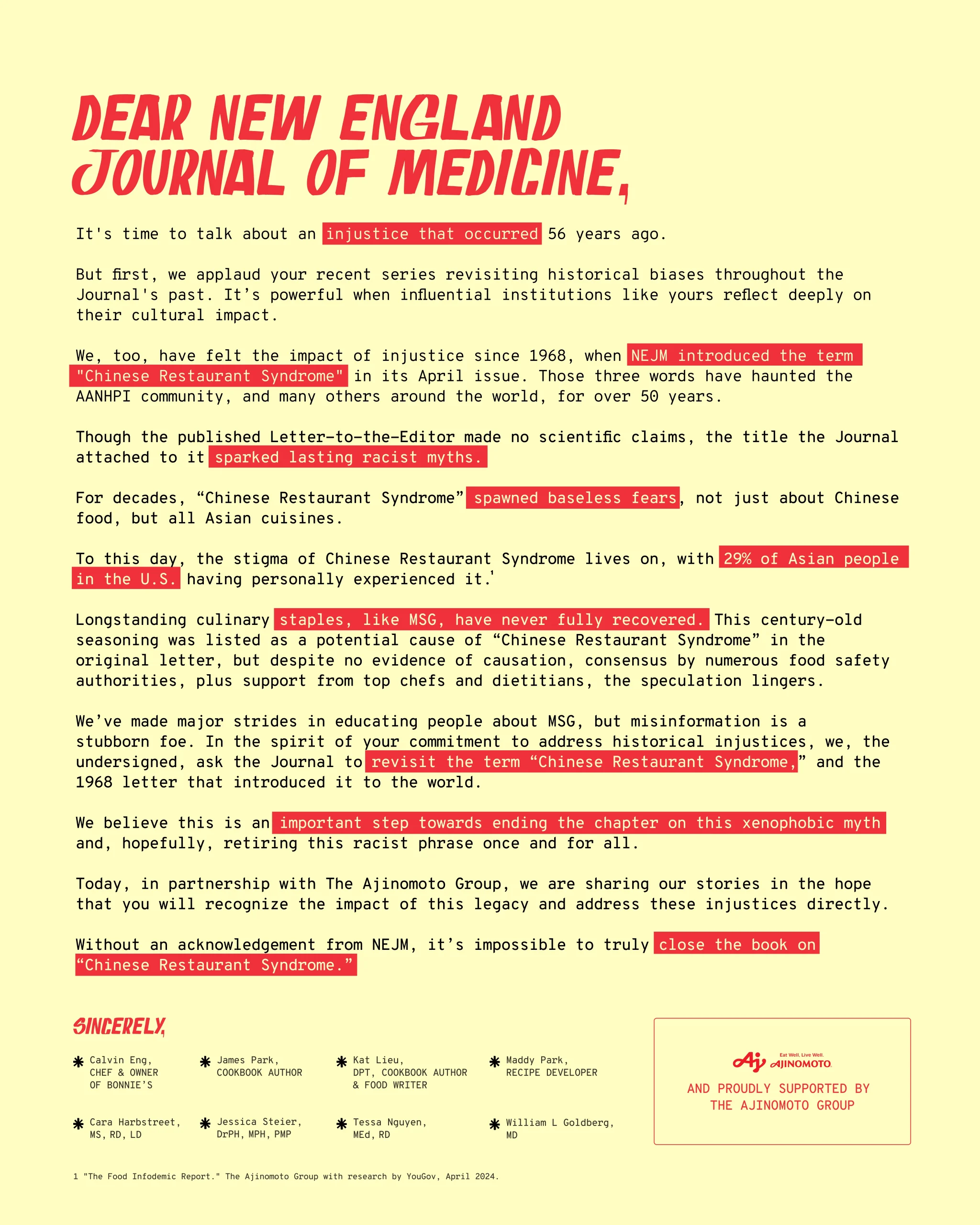

In 1968, a letter to the editor published by the New England Journal of Medicine noted that the author, a Chinese university professor, often ate Chinese food at a local restaurant but felt aftereffects, including numbness of his neck, arms and back, as well as headaches and dizziness. The letter ran with the headline, “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome,” and the title remains a meme to this day, with many Chinese restaurants posting signs announcing “No MSG” in the decades since.

To rehab the reputation of MSG in the U.S., Ajinomoto created a marketing campaign to counter what it considers the myth of “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.”

Governmental agencies, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, have tested MSG, with the FDA classifying it as “Generally Recognized as Safe.” The National Institutes of Health agreed with the FDA. The World Health Organization also tested MSG and found it safe. But the taint of that “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” letter has stayed with MSG ever since.

Read related story here.

Read related story here.

Japanese restaurants haven’t been the target of the anti-MSG message, nor have they made a big deal of either using or not using MSG. But the controversy has had one visible effect: Japanese community cookbooks, a staple of Japanese American churches, women’s groups and JACL chapters, used to include MSG, or the brand Aji-No-Moto, in most recipes.

The 1966 “Nisei Favorites” cookbook by the Gardena Valley Baptist Church Women’s Missionary Society matter-of-factly has “Ajinomoto” as an ingredient for a number of dishes, including Chinese Chicken (or Crab) Salad, Pork Curry on Rice, Kikkoman Shoyu Wieners, Flank Steak Teriyaki, Yaki Niku and more.

By the late 1970s, though, some cookbooks dropped MSG as an ingredient. A 1978 cookbook, “Treasured Recipes,” published by the Denver Buddhist Temple Women’s Assn., only lists “m.s.g” as an ingredient in several main dishes: Kombu Maki with Pork, Sweet and Sour Chicken and Chow Mein Soft Noodles.

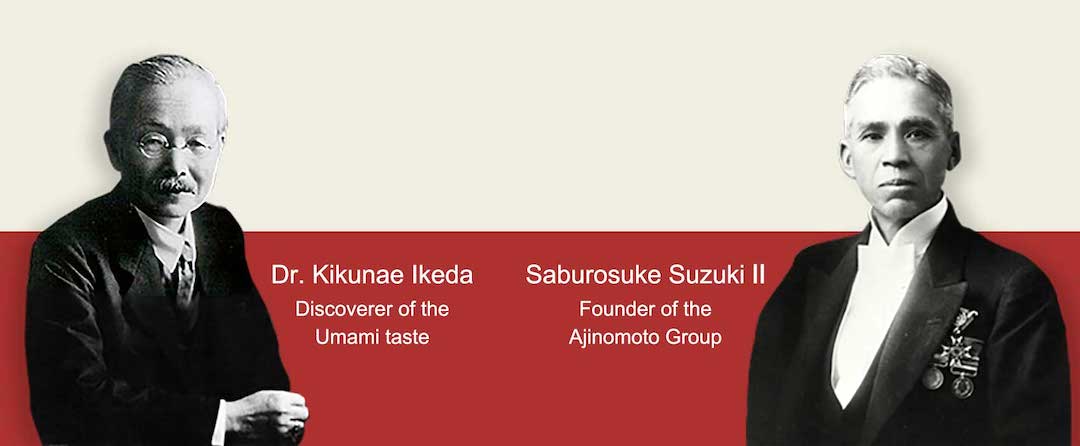

Aji-No-Moto founder Dr. Kikunae Ikeda and his company partner, Saburosuke Suzuki II (Photos: Ajinomoto Group)

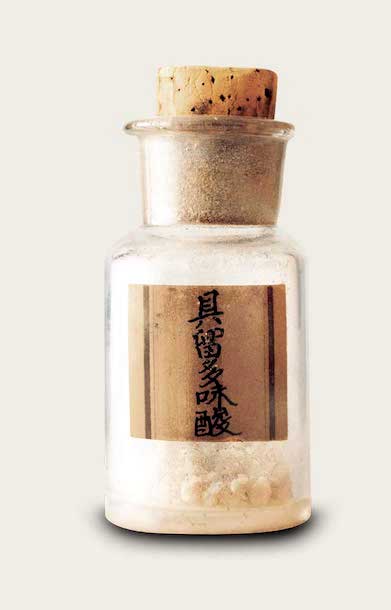

The glutamic acid extracted from kombu by Dr. Kikunae Ikeda in 1908

MSG was discovered and trademarked as “Aji-No-Moto,” essence of taste, in the early 1900s. Biochemist Dr. Kikunae Ikeda, who was trying to find the secret behind the delicious savoriness of his wife’s dashi soup, isolated the main ingredient: the kombu seaweed that she used as a base for the soup.

He called this flavor “umami” and helped popularize the use of the term. He also figured out how to crystallize the secret ingredient, and in 1908, he and a partner, Saburosuke Suzuki II, started Aji-No-Moto, the company that dominates the production of MSG in Japan and operates in 34 countries, manufacturing not just Aji-No-Moto but also packaged and frozen foods.

Costco stocks many Ajinomoto products, including gyoza and instant ramen bowls. (The company uses the one-word name, but the product is still spelled with the hyphens the way it was launched more than a century ago.)

Ajinomoto has led the way in rehabbing the reputation of MSG in the U.S., with a marketing campaign to counter what it considers is the myth of “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.” The company has signed on celebrity chefs such as David Chang and Eddie Huang to say that MSG isn’t harmful. It also successfully lobbied Merriam-Webster to add to its dictionary listing for Chinese restaurant syndrome to acknowledge that MSG doesn’t cause negative symptoms in healthy people and tone down the stigma against Chinese food and MSG.

It didn’t help when Covid spread throughout the world in 2020, and President Donald Trump called the disease “kung flu.” A wave of anti-Asian hate crimes spread along with the disease. Today, the aftereffects of that racism are still present, said Shigeyuki Takeuchi, associate general manager at Ajinomoto in Japan.

“It lingered for a long time, and then we’ve had these waves of anti-Asian sentiment,” he said. Takeuchi also noted that when the original Chinese restaurant syndrome phrase caused an outcry against Chinese restaurants, there was already strong sentiment in the country about emerging environmental and lifestyle issues.

He cited the 1962 book about environment science, “Silent Spring,” by Rachel Carson, which merged by the late 1960s with the emerging hippie, back-to-nature and even organic food movement, as laying the groundwork for the anti-MSG sentiment. “Of course, monosodium glutamate sounds chemical. People thought it was a bad substance. Even today, there’s a negativity, but that’s rapidly changing due to our efforts.”

Aji-No-Moto isn’t produced from kelp anymore like it was when Dr. Kikunae first discovered it and called it umami, the fifth taste (in addition to salty, sweet, sour and bitter — umami was officially named a scientific term in 1985). It’s made from grains such as wheat in the U.S. (and sugar in Brazil, where sugar cane is more abundant), that is fermented to create the glutamic acids that make MSG.

According to the Ajinomoto Group, MSG “is the purest form of umami and is widely used as a quick and easy way to add savory deliciousness to meals.”

(Photos: Ajinomoto Group)

Although Aji-N-Moto retreated from American grocery store shelves over the years, Takeuchi said Chinese restaurant syndrome didn’t hurt its sales in other markets worldwide. He admitted, though, that in Japan, sales of Aji-No-Moto have dropped, but not for the same reason as in the U.S.

“The interesting thing is that the powder itself had gone down in sales,” he said. “It’s because people who made powder seasonings or liquid seasonings, we only had shoyu (soy sauce to compete with), but people started to make ponzu and all sorts of specific seasonings for nabe hot pots or teriyaki sauce, and so people no longer had to use MSG, the single ingredient, because they already had umami.”

However, Takeuchi reported that there is currently a renaissance in interest for MSG and umami thanks, in part, to a popular social media influencer, and sales are rising.

But there are consumers who are still skeptical of MSG.

the original Aji-No-Moto in 1909

Noted Erin Yoshimura: “When I go eat dim sum, I have the same effect where eventually, I can start feeling my fingers getting swollen, and I get these, like, really weird little like bubbles popping in my head and feel like an out-of-body sensation. It’s mild, but it’s enough to notice.”

As a Japanese American in Colorado, she grew up eating Chinese food both in restaurants and at home and never noticed such effects before. She has recently been eating Japanese dishes cooked with a little bit of Aji-No-Moto and hasn’t felt any ill effects, so maybe the dim sum restaurants use more MSG.

“I think it’s probably because some people can handle it,” she said. “I think it’s just like any other thing, like wheat — some people can eat gluten, some people cannot. So yeah, I think it depends on your body makeup.”

One woman’s body definitely has a strong reaction to MSG. Journalist Anita M. Busch in Los Angeles wrote, “MSG is deadly to me because it causes neurotoxicity and overstimulates the vagal nerve and sends my heart into tachycardia that then goes into atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response of 180 to over 200 beats per minute.

“I end up in the cardiac intensive care unit each and every time I accidentally ingest it,” Busch continued. “I cannot even take a small amount of it, and it is disguised under many other names like modified milk protein or natural flavors, so I have learned through a dangerous game of Russian roulette. There are many names food manufacturers are allowed to use to hide this from the public, and that should never be the case. Asian food is particularly hard for me to even entertain trying, and that is hard when those in my family are 100 percent or 50 percent Japanese.”

It’s true that MSG is in a lot of foods, snacks and processed food products. Nacho Cheese Doritos, a favorite snack for many people, has MSG. So does (perhaps not surprisingly) instant noodles and ramen, soups, fast foods and frozen packaged foods. But some natural products, including produce, have MSG, too: tomatoes, mushrooms, cheese and, as mentioned before, kombu kelp and seaweed.

Calvin Eng, a young award-winning chef who operates a Cantonese American restaurant in Brooklyn named after his immigrant mother’s American nickname, Bonnie’s, is a spokesperson for Ajinomoto, who is upfront about using MSG in his cooking.

“I didn’t really know how to use MSG until I started cooking professionally; the restaurant I was at right before here was where I would order 100-pound barrels of Aji-No-Moto at a time, and that’s where I learned how to use it in cooking properly,” said Eng. “During that time is when I realized the power of MSG and what it can do. I always knew that it wasn’t bad for you, like I was educated enough on the topic to know that it’s a safe ingredient to use, so that was never my concern.

“But I found out about all the negative connotations that MSG does have,” he continued. “So, I wanted to be more open about the use of it and talk about it and just celebrate it in a way that hasn’t necessarily been done before, like we put it on our menu.”

It’s not just an ingredient in his food, either. He serves an “MSG Cocktail” made with gin or vodka and, yes, MSG. He’s even published a cookbook, “Salt Sugar MSG: Recipes and Stories From a Cantonese American Home.”

There isn’t such a pushback from Japanese restaurants, which haven’t suffered from an anti-MSG movement over the years. Some restaurants do not use MSG, but many quietly do.

In Denver, Takashi Tamai, the owner and chef of award-winning Ramen Star restaurant, said he doesn’t use MSG and prefers to flavor his dishes the old-school way with ingredients that might take longer or be more expensive to use.

But Miki Hashimoto, award-winning chef and owner of Tokio restaurant, also in Denver, said he thinks “pretty much for sure, 99 percent of Japanese restaurants use MSG. If they say they do not use Aji-No-Moto, I sip their miso soup, and I can tell immediately.”

He adds that he uses MSG in small amounts to a few items, and never in sushi, to achieve a balance of flavors that enhances umami.

With Aji-No-Moto making what appears to be a cultural comeback, we may eventually see those ubiquitous bottles with the bright red tops on our kitchen tables once again.

This article was made possible by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL Redress Strategist Grant Ujifusa.