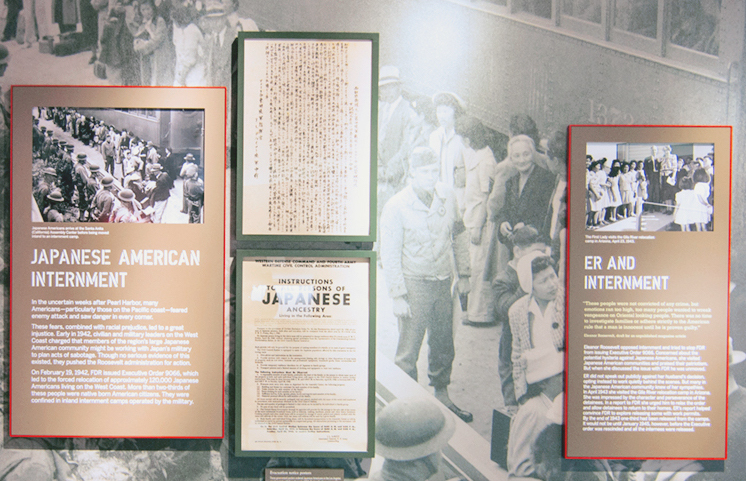

Japanese American Internment section is part of the FDR Library’s permanent exhibition. (Photo: Patti Hirahara)

‘Images of Internment: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II’ Is Featured at the Library and Sheds Light on a Very Special Relationship

By Patti Hirahara, Contributor

The FDR Presidential Library and Museum is located in Hyde Park, N.Y., and it is very unique in many ways.

According to the National Archives, “The Presidential Library system formally began in 1939, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt donated his personal and presidential papers to the Federal government. At the same time, Roosevelt pledged part of his estate at Hyde Park to the United States, and friends of the president formed a nonprofit corporation to raise funds for the construction of the library and museum building.”

Roosevelt’s decision stemmed from a firm belief that presidential papers are an important part of the nation’s heritage and should be accessible to the public. He asked the National Archives to take custody of his papers and other historical materials, as well as administer his library.”

“The library opened June 30, 1941, and it is the first presidential library and the only one that was actually used by a sitting president,” said FDR Presidential Library Director Paul Sparrow.

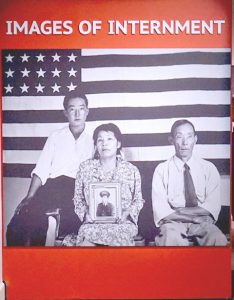

Art on display at the entrance to the FDR exhibition “Images of Internment — The Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II.” (Photo: Patti Hirahara)

This year, in commemoration of the 75th anniversary of Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066, the FDR Presidential Library has opened its new exhibition “Images of Internment — The Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II.”

This exhibit is the result of two years of planning and development, and in seeing the exhibit’s name, a scholar might wonder why the words “internment” and “incarceration” were used in the title.

“The curator was very aware of the issues surrounding the use of the term ‘internment,’ and we wanted to be accurate,” according to Sparrow. “But most people know it by that name. So, we wanted to make it clear that this was a photographic exhibition about the ‘internment,’ but also that it involved the incarceration of American citizens, not just the internment of foreign nationals.

“This exhibit is really a companion to last year’s exhibit on Pearl Harbor — we wanted to show cause and effect,” Sparrow continued. “But the most important message is that to truly understand a great leader, you must look at both their accomplishments and their failures. In this case, one of the great champions of human rights was pressured to incarcerate 80,000 American citizens because of racist hysteria and ‘national security concerns.’ It is a common thread in American history that national security issues are used to violate constitutional rights, particularly of minority populations.”

The exhibition opens with a section that explores the following questions: “Why Did FDR Issue Executive Order 9066?” and “What Did the Executive Order Do?” The opening section also examines opposition to the Executive Order and the special role of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who opposed her husband’s executive order and worked to assist Japanese Americans confined in the government camps.

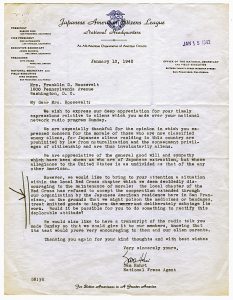

The Japanese American Citizens League’s tie to this story is part of its relationship with Eleanor Roosevelt. On Jan. 13, 1942, Sam Hohri, national press agent for the JACL, wrote a letter to Mrs. Roosevelt at her 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. address.

He stated on behalf of the JACL: “We wish to express our deep appreciation for your timely expressions relative to aliens, which you made over your national network radio program Sunday.

“We are especially thankful for the opinion in which you expressed concern for the morale of those who are now classified enemy aliens, for Japanese aliens residing in this country are prohibited by law from naturalization and the consequent privileges of citizenship and are thus involuntarily aliens,” Hohri continued. “We are appreciative of the general good will and sympathy, which have been shown us who are of Japanese extraction, but whose allegiance to the United States is as undivided as that of any other American.”

“Moonlight Over Topaz, Utah” watercolor on silk, 1942, was painted by artist Chiura Obata (1885-1975) and was presented to Eleanor Roosevelt by the JACL in a 1943 White House ceremony. Mrs. Roosevelt displayed this painting in her New York City apartment until her death. (Photo: Courtesy of the Obata Family)

This original letter is on display in the exhibition as well as a Chiura Obata watercolor on silk created in 1942 titled “Moonlight Over Topaz, Utah.” Obata (1885-1975) was teaching in the art department at the University of California, Berkeley, when Executive Order 9066 was signed. He and his family were confined at the Central Utah (Topaz) camp, where he established an art school and continued his work as a painter.

In May 1943, shortly after the first lady’s well-publicized visit to the Gila River camp in Arizona, a delegation from the JACL visited the White House to express its gratitude for her concern for the treatment of Japanese Americans.

During the group’s visit, its members presented Obata’s painting of the Topaz camp to Eleanor Roosevelt, and on June 16, she sent a letter to Obata, thanking him for the painting. After the end of World War II, Obata returned to California and was reappointed to his university position.

Eleanor Roosevelt displayed this painting in her New York apartment until her death in 1962. It was subsequently donated to the FDR Presidential Library. To this day, it shows how important and precious this time in history was to the first lady.

What is also interesting are the slogans that appear on the JACL headquarter’s letterhead — “An All-American Organization of American Citizens … For Better Americans in A Greater America” — from its 1623 Webster St. address in San Francisco in 1942.

The new exhibition was created by the staff of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, who worked closely with a panel of historians that then reviewed and approved the exhibition text. Panel members included Dr. Allida Black, a historian and author; Professor Greg Robinson of the Universite du Quebec a Montreal; and Professor David Woolner of Marist College.

There are 209 photographs on display in the exhibition.

“We selected photographs that documented the entire story of the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II — beginning with depictions of life in Japanese American communities on the West Coast prior to Executive Order 9066, followed by the posting of the ‘evacuation’ order in those communities; the forced removal and transportation of Japanese Americans to the temporary ‘assembly centers’; conditions of life in those ‘assembly centers’; the subsequent transportation of Japanese Americans to the 10 camps constructed in the nation’s interior; life inside those camps; the story of Japanese Americans who served in America’s military during the war, especially the famous 442nd Regimental Combat Team; the government’s flawed program to separate ‘loyal’ and allegedly ‘disloyal’ Japanese Americans; and, finally, the closing of the camps and the postwar efforts that led to a formal apology by the government and payments of $20,000 to survivors,” stated Herman R. Eberhardt, supervisory museum curator of the FDR Presidential Library and Museum.

Most of the photographs featured in the exhibition were shot by War Relocation Authority photographers Clem Albers, Hikaru Iwasaki, Dorothea Lange and Francis Stewart, with a large selection of photographs shot by famed landscape photographer Ansel Adams, who obtained permission to take photographs in Manzanar.

Other War Relocation Authority photographers’ work are also shown, along with a small group of photographs selected from the thousands taken by two amateur photographers, George and Frank C. Hirahara, a father and son who were incarcerated in Heart Mountain, Wyo. Their photographs were taken directly inside the camp, thus giving a more personal viewpoint of life there from actual incarcerees.

“We received special assistance from the staff at the Still Picture Branch of the National Archives and Records Administration, which holds the records — including photographs — of the War Relocation Authority; the staff of the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress, which holds the Manzanar photographs shot by Ansel Adams; the staff of the Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections at the Washington State University Libraries, which holds the photographic collection by George and Frank C. Hirahara; and Chief of Interpretation Alisa Lynch and the staff of the Manzanar National Historic Site, who generously lent us a copy of their film ‘Remembering Manzanar,’ which is shown in the exhibition,” Eberhardt added.

“The reaction to the exhibition has been extremely positive, and more importantly, we believe we have dramatically increased the number of Japanese and Asian American visitors — because we are now telling THEIR story as well,” Sparrow said.

To educate the public on this time in history, the FDR Library is hosting a whole series of programs featuring authors, historians, artists and people who have personal stories to tell in addition to reaching out to local schools. There is also information available on the library’s virtual tour (http://www.fdrlibraryvirtualtour.org/page07-15.asp), a You Tube video about the incarceration (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-iVxs2xuYc), as well as Sparrow’s personal commentary on the images shown in “Images of Internment” (https://fdr.blogs.archives.gov/2017/02/17/images-of-internment/).

The library also has a section in its permanent exhibition that also details Japanese American internment history from its inception during World War II.

On the 75th anniversary of the signing of Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 2017, acclaimed actor-activist George Takei, Theodore Roosevelt’s great-great grandson Kermit Roosevelt and Sparrow held a conversation presentation to open the exhibition at the FDR Library.

“Mr. Takei has such authenticity on this issue that his words carry great weight,” Sparrow recalled. “He was so open and honest about his experience and about what it means for ALL Americans. I think it was also very emotional for him — some of the photographs became very personal. One photo in particular was of a young boy looking through the slats of a cattle truck — when he saw it, he choked up and said he remembered that moment so well in his own experience. Just a 5-year-old boy, loaded onto a truck and watching his home fade away in the distance as the truck drove away.”

The “Images of Internment” exhibition will close on Dec. 31, and nothing is on the schedule for the next couple of years in having any other exhibitions on the Japanese American incarceration at the library.

Approximately 194,000 individuals visited the FDR Presidential Library and Visitor Center last year, with many having their own special connection to that part of the American story.

“I think one of the most important parts to see of the FDR Library exhibit is the section on his polio,” said Sparrow. “The film there is very powerful. Seeing his steel braces, the story behind the March of Dimes and how FDR’s efforts eventually led to finding a cure for polio is one visitors should see. Most people don’t know why his face is on the dime. It’s because he created the March of Dimes, the only medical charity that ever cured the disease it was created for.”

Visitors planning on going to Hyde Park should plan to spend a whole day to see the FDR Presidential Library and Museum, FDR’s home, Eleanor Roosevelt’s home at Val Kill, Top Cottage, the Vanderbilt mansion and, of course, the great local food at the Culinary Institute and the Walkway Over the Hudson.

In personally coming to the FDR Presidential Library, a person might have mixed feelings, especially those who were incarcerated behind barbed wired during WWII. But in seeing the various correspondence and information about the Japanese American incarceration, the FDR Library gives an unbiased view of what happened. It wants to educate people about this dark time in history to ensure that this will never happen again.

For further information, please check the FDR Presidential Library and Museum website at https://fdrlibrary.org/.