Representing the Little Tokyo Historical Society’s 2025 Wakamatsu Pilgrimage are (back row, from left) Ruth Watanabe, David Nagano, Bill Watanabe, Michael Okamura and (front row, from left) Naomi Hirahara, Paula Miura, Pauline Wada, Cindy Abrams and Yuko Gabe. (Photo: Courtesy of David Nagano)

Los Angelenos trek together to visit tunnels excavated by

Chinese workers and the site of early migration from Japan.

By Naomi Hirahara, P.C. Contributor

Camp pilgrimages have become an important rite of passage, ever since activists gathered on a winter day in December 1969 in the Owens Valley to mark the experience of their ancestors at the Manzanar concentration camp. But thanks to Kenji Taguma’s Nichi Bei Foundation, there is now the Wakamatsu and Angel Island pilgrimages to commemorate early Japanese pioneers arriving to California.

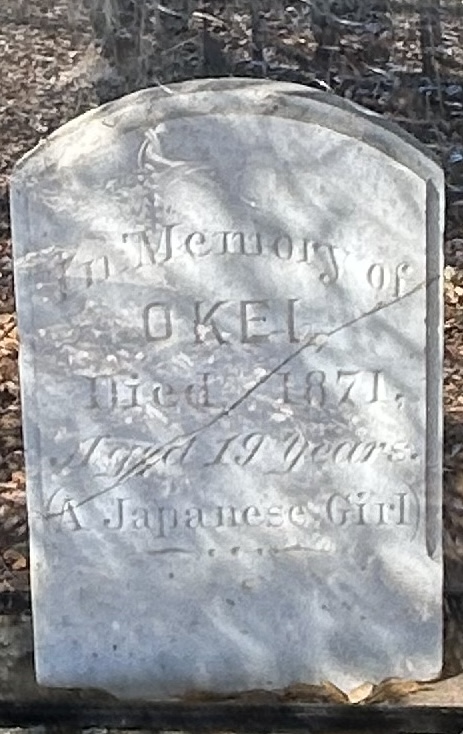

The headstone for Okei’s grave is now cracked and enclosed. (Photo: Dave Nagano)

Members of the Little Tokyo Historical Society, which was established 19 years ago, have wanted to take a road trip to participate in these immigration pilgrimages some time. For Michael Okamura, society president, visiting the grave of Okei — a member of the Wakamatsu Colony and the first woman of Japanese descent to be buried on American soil — was essential because of his own family connections. The original colonists, some from the samurai class, came to California’s Gold Country from Aizu-Wakamatsu in Fukushima Prefecture in 1869 after being defeated in the Boshin civil war.

“My great-uncle was a longtime member of the Nanka Fukushima Kenjinkai, including serving as president, so he had visited the grave marker site multiple times,” said Okamura. A frequent visitor to Fukushima, Okamura has even paid tribute to the Okei memorial monument in Aizu-Wakamatsu. “I think I may be one of the few Nikkei in America who has been to both Okei grave marker sites.”

In contrast, another traveler with the historical society, Pauline Wada, had never before heard of the Wakamatsu Colony. Indeed, in 2011, when I made the trek with my husband to see the gravestone (then on private property), located in the back of Gold Trail Elementary School, there was little to distinguish the area, despite being established as a California State Historic Site in 1966. I was curious to see the new improvements and interpretive features of the Wakamatsu Colony since the acquisition from private owners to now management by the American River Conservancy as not only a pilgrimage site but also a working farm.

We nine members of the historical society gathered around 5 a.m. on Oct. 3 in Pasadena, Calif. Carrying overnight bags and containers of freshly made Spam musubi, sticky rice and other snacks, we set out in a long white van to make a 500-mile drive up Highway 5, first to Truckee, the site of tunnels created by Chinese railroad workers across from Donner Pass, then to stay the night in Auburn and finally gather with more than 275 people at the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm Colony.

We were only able to experience the rugged adventure of following the path of Chinese railroad workers through our guide, Phil Sexton, an active member of the 1882 Foundation, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit devoted to broadening public awareness of the history and continuing significance of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Sexton, who resides in nearby Auburn, took us on a journey over glacial polish and granite boulders across from Donner Lake and Donner Pass.

Bill Watanabe walks through a graffiti-marked Union Pacific tunnel excavated more than a century ago by immigrant Chinese laborers. (Photo: Dave Nagano)

For us Angelenos, the 45-degree temperature and light drizzle were a bit of a challenge, not to mention the ascent up to the location where the workers camped and detonated black gunpowder that had been stuffed into 2.5-inch diameter holes drilled into solid rock. We saw the railroad line where locomotives carried rubble away from the construction area and encountered 150-year-old remnants, such as rusted can lids and square nails. Our final destination — the tunnels of the Union Pacific — were urbanized by colorful graffiti, quite a contrast to the natural beauty of the mountains and pine trees.

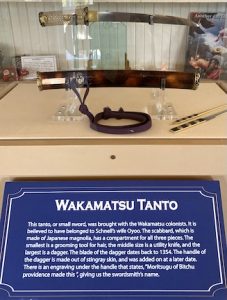

Display case at the site of the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm Colony shows a tanto believed to be owned by colonist Oyoo Schnell. (Photo: Dave Nagano)

Okamura, who only wore a sweatshirt to keep him warm and dry, commented: “We and the U.S. have to thank the Chinese railroad workers for the historic work they did. It also made me think of the back-breaking work of the Issei men who also worked on the railroads in the late-19th century and early-20th centuries.”

In comparison to the wet and physically taxing experience in Truckee, the Wakamatsu Pilgrimage represented order, comfort and celebration. I was impressed by how much the property had developed over the past decade, with the renovation and interpretive exhibitions of the Veerkamp farmhouse, where Okei and another colonist, Matsunosuke Sakurai, had worked after the colony disbanded. The Okei gravestone, damaged by a crack, is displayed in a glass case now. Flowers and even a jizo statue with a red cap were displayed at the site as Rinban Yuki Sugahara of the Buddhist Church of Sacramento delivered a blessing for that day.

New plaques and monuments now adorn the site. There’s a marker at the giant keyaki or Japanese elm tree that the Wakamatsu colonists had planted, as well as a stone marker commemorating Sakurai, who was the one who had led a campaign to produce a gravestone for his friend, Okei, who had died from a sudden illness at 19 years of age in 1871.

LTHS President Michael Okamura engages in ondo at the Wakamatsu Pilgrimage in October. (Photo: Dave Nagano)

Close-up on Okei’s grave marker.

In addition to tours of the grounds, the pilgrimage included genealogical workshops, a bento lunch and ondo dancing. It was wonderful to bump into both old friends, including another writer, Karen Tei Yamashita. Introduced onstage were eight descendants of the original Wakamatsu Colony, the newest discovered one being Andrea Lashley, who is originally from the New York/New Jersey area. During the pandemic, her teenage son had requested a DNA test from ancestry.com, an unusual request coming from someone so young. The results of that test led Lashley and her son to discover that they had not only Japanese DNA, but were related to Kuninosuke Masumizu, the only original colonist who remained in California and wed an African American and Native American woman.

This discovery was not a surprise to Lashley’s friends, who teased, “I knew something about you didn’t belong here.” To find ties to California, including relatives Aaron Gibson and Barbara Johnson, even inspired Lashley to make the move to San Francisco as a nursing student at the University of California at San Francisco.

After the festivities, our Little Tokyo group piled back into our white van. Not all of us in the vehicle had direct family members who had been held in a World War II concentration camp. Not all of us were even Japanese American. What tied us together was the willingness to get into that van on an early morning and trust our drivers to get us to our destination.

“There was such great enthusiasm and care for each other that it made me long for another road trip,” said Nagano. She may not have to wait long: The Nichi Bei Foundation is planning another gathering to mark the immigration station that processed early Japanese immigrants — the Nikkei Angel Island Pilgrimage — for next year.

Naomi Hirahara is the author of more than 20 nonfiction history books and mystery novels. Her next historical mystery, “Crown City,” set in 1903 Pasadena, will be released in February 2026. Her web series, “Silk,” on Discover Nikkei, is a fictional retelling of the Wakamatsu colony.

A highlight of the Wakamatsu Pilgrimage was the attendance of the descendants of the original colonists, some of whom had traveled as far as Japan and the Marshall Islands. Pictured (from left) are Nancy Ukai, Nichi Bei Foundation board chair; Naori Shiraishi, a descendant of Matsugoro Oto; Aaron Gibson, Barbara Johnson and Andrea Lashley, descendants of Kuninosuke Masumizu; Atsuko, Soun and Karen Kaname with Ayako Matsufuji, descendants of Sakichi and Nami Yanagisawa; and Kenji Taguma, Nichi Bei Foundation president. (Photo: David Nagano)