P.C. Staff and wire report

Hiroshi Miyamura (Photo: George Toshio Johnston. © 2017. All rights reserved. May not be used without permission.)

Medal of Honor recipient Hiroshi Miyamura, born and raised in Gallup, N.M., and better known by his sobriquet “Hershey,” died early Tuesday morning, Nov. 29 in Phoenix, where he had been living with daughter Kelly Hildahl. The WWII and Korean War veteran was 97.

By the time Miyamura had joined the Army in January 1945 and assigned to the segregated and storied 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the war in the European Theater had begun to wind down. With Germany’s surrender by May, he avoided seeing combat. Five years later, however, when the United States became embroiled in the Korean War, Miyamura, who was in the Army Reserve, was recalled to active-duty status.

It was in that conflict where Hershey Miyamura’s valor would earn him the nation’s highest military decoration.

“I was greatly saddened to hear of his passing, as he was truly the best representative for the Japanese Americans during the Korean War,” said fellow Japanese American Korean War veteran Harumi “Bacon” Sakatani. “His bravery to defend his comrades was in the best tradition of the American way. His humbleness throughout his life showed what a great man he was.”

“The Japanese American Veterans Association is saddened to learn of the passing of Hiroshi ‘Hershey’ Miyamura,” said JAVA President Gerald Yamada, who noted that Miyamura served as the organization’s honorary chairperson. “As a combat veteran of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team during World War II and as a Medal of Honor recipient for his valor during the Korean War, he is a role model for those who make military service their chosen career. His spirit and support will be missed.

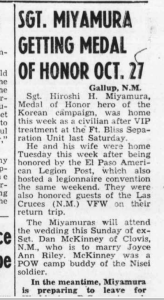

This screenshot from the Oct. 16, 1953, Pacific Citizen reported the upcoming Oct. 27 ceremony at which Hershey Miyamura would receive his Medal of Honor.

Ken Hayashi, a Vietnam War veteran and friend of Miyamura, told the Pacific Citizen, “If the government said we wanted to create a person to represent the Medal of Honor and the country, they couldn’t have done a better job than then Hershey. He was just such a humble and gracious man — and such a patriot. You just couldn’t ask for more in a person.”

For Mitchell Maki, CEO and president of the Go for Broke National Education Center, Miyamura “embodied America’s promise.”

“The son of immigrants and a veteran of World War II and the Korean War, he demonstrated that being an American is not a matter of the color of one’s skin, the nation of one’s ancestry, or the faith one chooses to keep,” said Maki, speaking for GFBNEC. “Being an American is about courage and service to others. Beyond being a Medal of Honor recipient, he was a gentle soul with a keen sense of humor and a heart filled with compassion.”

Hershey Miyamura was the fourth of seven children born to Yaichi and Tori (née Matsukawa) Miyamura, Issei who had emigrated from Japan and settled in New Mexico. His mother died when he was 11. As for his nickname, “Hershey,” that was because an elementary school teacher couldn’t pronounce his first name, Hiroshi.

Because the Miyamura family was living outside the Western Exclusion Zone during WWII when President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, they were spared from being uprooted and incarcerated in U.S. government detention centers as were more than 120,000 ethnic Japanese, most of whom were U.S. citizens, who were living along the West Coast.

Hershey and Terry Miyamura. (Courtesy of the Miyamura family)

That was not the case, however, for Miyamura’s Los Angeles-born wife, Tsuruko “Terry” Tsuchimori. With her family, she had been incarcerated at the Poston WRA Center in Arizona. After the war, she was living in Winslow, Ariz., and the two married in June 1948.

As a member of the Army Reserve, Miyamura was called back to active duty when the U.S. entered the Korean War in June 1950.

On the night of April 24, 1951, near Taejon-ni, Miyamura’s company came under attack by an invading Chinese force. Cpl. Miyamura ordered his squad to retreat while he stayed behind and continued to fight, giving his men enough time to evacuate. Miyamura continued to fight in order to protect his fellow soldiers.

Miyamura and fellow squad leader Joseph Lawrence Annello, of Castle Rock, Colo., were later captured. By that time, it was estimated that Miyamura had killed more than 50 enemy soldiers.

Though wounded, Miyamura carried the injured Annello for miles until Chinese soldiers ordered him at gunpoint to leave Annello by the side of a road. Miyamura refused the orders until Annello convinced him to put him down.

Annello was later picked up by another Chinese unit and taken to a POW camp, from which he escaped.

President Eisenhower awards Hershey Miyamura the Medal of Honor in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 27, 1953.

Miyamura was held as a prisoner for two years and four months. Upon his release, he weighed less than 120 pounds. After returning stateside, he was presented the Medal of Honor by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. It had been awarded in secret while he was still a prisoner of war.

“I never ever thought I would receive the Medal of Honor for doing my duty, which I thought that’s all I was doing, was my duty,” Miyamura said in the 2018 Netflix documentary “Medal of Honor.”

Miyamura and Annello later met up and would remain lifelong friends until Annello’s death in 2018. The story of their friendship was told in “Forged in Fire: The Saga of Hershey and Joe,” written by the late Vincent H. Okamoto, who was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his service in the Vietnam War and later appointed to be a Los Angeles Superior Court judge.

After the Korean War, Miyamura returned to Gallup as a hero, a word he chose not to use to describe himself. More than 5,000 people came to meet his train. He spent much of the rest of his life working in town as an auto mechanic.

Hershey Miyamura and Sen. Daniel Inouye greet one another in this Pacific Citizen file photo. (Photo: Lilly Fukui)

In his Living History documentary in the Congressional Medal of Honor Society library, Miyamura reflected on the soldiers who deserved recognition but never received it.

“There are so many Americans who don’t know what the Medal represents or what any soldier or servicewoman or man does for his country. And I believe one of these days — I hope one of these days — they will learn of the sacrifices that a lot of the men and women have made for this country,” he said.

Gallup, N.M., is the home of Miyamura High School, named after Hiroshi ”Hershey” Miyamura. (Photo: Jon Kaji)

Miyamura remained active in veterans’ issues and gave annual summer lectures to military members in Gallup, N.M., where a street, a park and a high school have been named in his honor. The talks drew hundreds of servicemen and servicewomen over the years.

In 2019, an aide announced that Miyamura had likely given his last public talk due to declining health.

New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham and Navajo Nation Vice President Myron Lizer both called Miyamura a hero, saying he will be missed by many who are forever grateful for his service.

Reflecting on Miyamura’s life as an American soldier and as a civilian, GFBNEC’s Maki said to think of him “simply as a warrior … I think does a disservice to Hershey,” he said. “The man demonstrated what it means to be an American in terms of service to others and service to the nation. And he did that in so many different ways, including the military, but also off the battlefield.”

Miyamura’s funeral service took place on Saturday, Dec. 10 at Sunset Memorial Park in Gallup, N.M.

Miyamura was predeceased by his wife, Terry in December 2014, and his siblings Chiyoko Herrera, Momoko Saruwatari, George Miyamura and Kei Miyamura.

This photograph of the Hiroshi “Hershey” Miyamura statue in his hometown of Gallup, N.M. (Photo: Jon Kaji)

Miyamura is survived by his sons Mike (Marianne) Miyamura and Pat (Jill) Miyamura, and his daughter, Kelly (Clay) Hildahl; his sisters Michiko Yoshida, Suzi Tashiro and Shige Sasaki; his granddaughters Megan Miyamura, Marisa (Joe) Regan and Madison Miyamura; his grandson, Ian Miyamura; and his great-grandchildren Marshall Miyamura, Thomas Regan, Emi Regan, Michael Regan, Lora Regan.

For those who would like to donate to the memory of Miyamura, support may be the given to the Miyamura High School Scholarship Foundation by making donations out to either “McKinley Education Foundation” (annotate the Memo line as HMHS Scholarship Fund) or “HMHS Scholarship Fund,” and mailed to: ATTN: Gerald Herrera MEF, Treasurer, 1038 W Layland Ave., Queen Creek, AZ 85140-3532.

(Associated Press contributed to this report.)