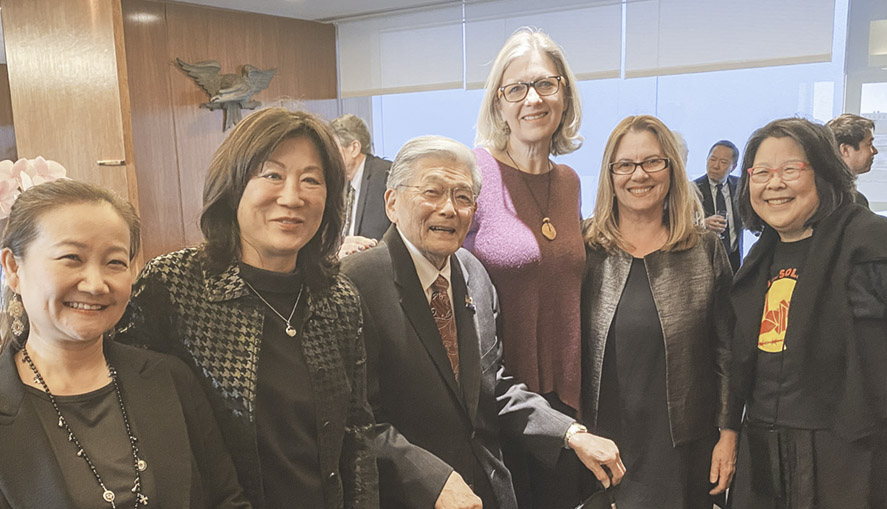

Noriko Sanefuji, Shirley Ann Higuchi, Sec. Norman Mineta, Dr. Anthea Hartig, Ann Burroughs and Nancy Ukai before the start of the program. (Photo: Julie Yoshiko Abo/Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation)

In observance of Day of Remembrance, a special panel discussion is held at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

By Ray Locker

Shocked and angered by the threat of a public auction that threatened to scatter art and artifacts created by prisoners at War Relocation Authority camps, Japanese American activists bonded together to create an enduring partnership, a panel at the National Museum of American History said on the 78th anniversary of Executive Order 9066.

In March 2015, a New Jersey-based auction house announced it would sell works collected during World War II by Allen Hendershott Eaton, a folk-art historian and author of the 19 52 book “Beauty Behind Barbed Wire.”

After legal action taken by the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, led by Shirley Ann Higuchi, and a social media campaign by Nancy Ukai, the auction was stopped, and the art was sold to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles. Actor and author George Takei donated the money to pay for the art.

“In protest, there can be healing,” Ukai said at the discussion, which was moderated by JANM President and CEO Ann Burroughs. “We found our voices to work together and protect our history.”

The activism behind the fight over the auction led Higuchi, Ukai and the leaders of groups fighting to preserve the legacy of the Japanese American incarceration to create the Japanese American Confinement Sites Consortium (JACSC), which is meeting in Washington, D.C., in late March.

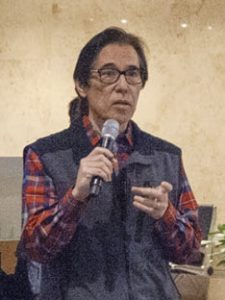

Dr. Phil Tajitsu Nash speaks during the program. (Photo: Richard Strauss/Smithsonian National Museum of American History)

JACSC was started in 2016 to bring 27 groups together to advocate for the continued support of the federal Japanese American Confinement Sites program, which funds the restoration of the former WRA camps and other detention centers around the country.

Last year, the program distributed $2.9 million to 19 groups to support such projects as the restoration of a root cellar at the Heart Mountain, Wyo., site and an oral history project by the Japanese American Citizens League.

Last month, the budget proposed by the White House contained no money for the program, the same as in 2018 and in 2019. In both years, however, a bipartisan group in Congress reinstated the funding, and JACSC leaders are working to ensure that happens again.

David Inoue, executive director of the JACL, and Floyd Mori, a former JACL national president/executive director and longtime community leader, appeared on the panel to talk about their work in maintaining the program.

Fighting the Auction

Higuchi told the packed audience that she and her board were angered at the intended sale of the art by the Rago Arts auction house. They did not believe Eaton or his heirs intended for the art, which was donated by incarcerees who wanted it exhibited publicly, to be sold publicly.

Even though the collection was appraised at only $26,500, the Heart Mountain board raised $50,000 to buy the art, reasoning that if Rago rejected the offer, it would show bad faith on their part.

Rago and the then-anonymous seller rejected the offer, and Heart Mountain hired a New Jersey law firm that Higuchi knew from her work as an attorney for the American Psychological Assn. They announced they would file an injunction to stop the auction, and Rago stopped the sale the same day.

“When I think back to those days, the most significant thing that occurred was the contribution made by Shirley Higuchi and the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation to bring the lawsuit to stop the sale of the Eaton Collection,” said the Hon. Norman Mineta, a former Heart Mountain incarceree and later a member of the U.S. House and Secretary of Commerce and Transportation.

In California, Ukai and a small group of activists were creating a Facebook page — Japanese American History: Not for Sale — that highlighted some of the art at risk of being scattered around the country.

“This was our cultural heritage from when we were held” in camps, Ukai said.

Once Japanese Americans could see the art up for auction, they realized the parts of their heritage that were set to be cast adrift around the country, Ukai said.

Ukai is now one of the leaders of Tsuru for Solidarity, which advocates for the rights of immigrants detained by the government. The group will hold a major rally, complete with 120,000 folded paper cranes, in Washington, D.C., on June 5-7. [Editor’s note: This event has subsequently been postponed. See story here.]

Clement Hanami, a curator at JANM, has cared for the art since the museum gained control of the collection. He assembled a show of some of the prominent pieces, “Contested Histories,” that has toured the country and was at the National Museum of American History to accompany the panel discussion.

Pictured in front of a case holding Allen Hendershott Eaton’s book “Beauty Behind Barbed Wire” are JANM’s Clement Hanami, JACL’s Matthew Weisbly and NMAH’s Noriko Sanefuji. (Photo: Julie Yoshiko Abo/Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation)

“We felt we had to do something very important with this work,” Hanami said. “We had to make it more accessible.”

Hanami showed a short video of the exhibit being shown at locations around the country. Some of those who saw the artifacts created by their incarcerated ancestors said it awakened a sense of Japanese American identity that they had hidden for decades.

Such reactions, Higuchi said, show the federal government’s plan for Japanese Americans during the war actually worked: Japanese Americans were separated from their homes, community and culture and forced to become an assimilated “model minority.”

“They put us in the middle of nowhere,” she said. “It broke our families up. Growing up, I had no Japanese American friends. My parents were taught not to talk about it. Without working with the community, I would have lost a big part of my life,” said Higuchi.

Panel participants included (from left) Clement Hanami, Nancy Ukai, Shirley Ann Higuchi, Sec. Norman Mineta, Floyd Mori, David Inoue and moderator Ann Burroughs. (Photo: Richard Strauss/Smithsonian National Museum of American History)