Kathleen Burkinshaw (left) and her daughter, Sara, holding a banner Sara made for Ribbon International 2020 (Photo: Courtesy of Kathleen Burkinshaw)

Recalling one hibakusha’s memories of Hiroshima and why it was so much greater than two paragraphs and a general photo in a school textbook.

By Kathleen Burkinshaw

Seventy-five years ago, my mother, Toshiko Ishikawa, stood outside chatting with her best friend on a sunny August morning. Then, an ear-shattering popping noise, followed by an intense burst of white light. The ground shook beneath them as they hugged each other and screamed. My mother was 12 years old when the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan.

I was 5 years old when I first remember waking up to my mother’s blood-curdling screams, the result of recurring nightmares— especially in the summer — that plagued her often since that horrific day. She’d tell me that it was nothing I needed to worry about.

In fact, for most of my childhood, I didn’t know that she was even from Hiroshima! She told everyone she was from Tokyo. My mother would not teach me Japanese, cooked only a few Japanese dishes and if you visited, you wouldn’t see Japanese décor in our home.

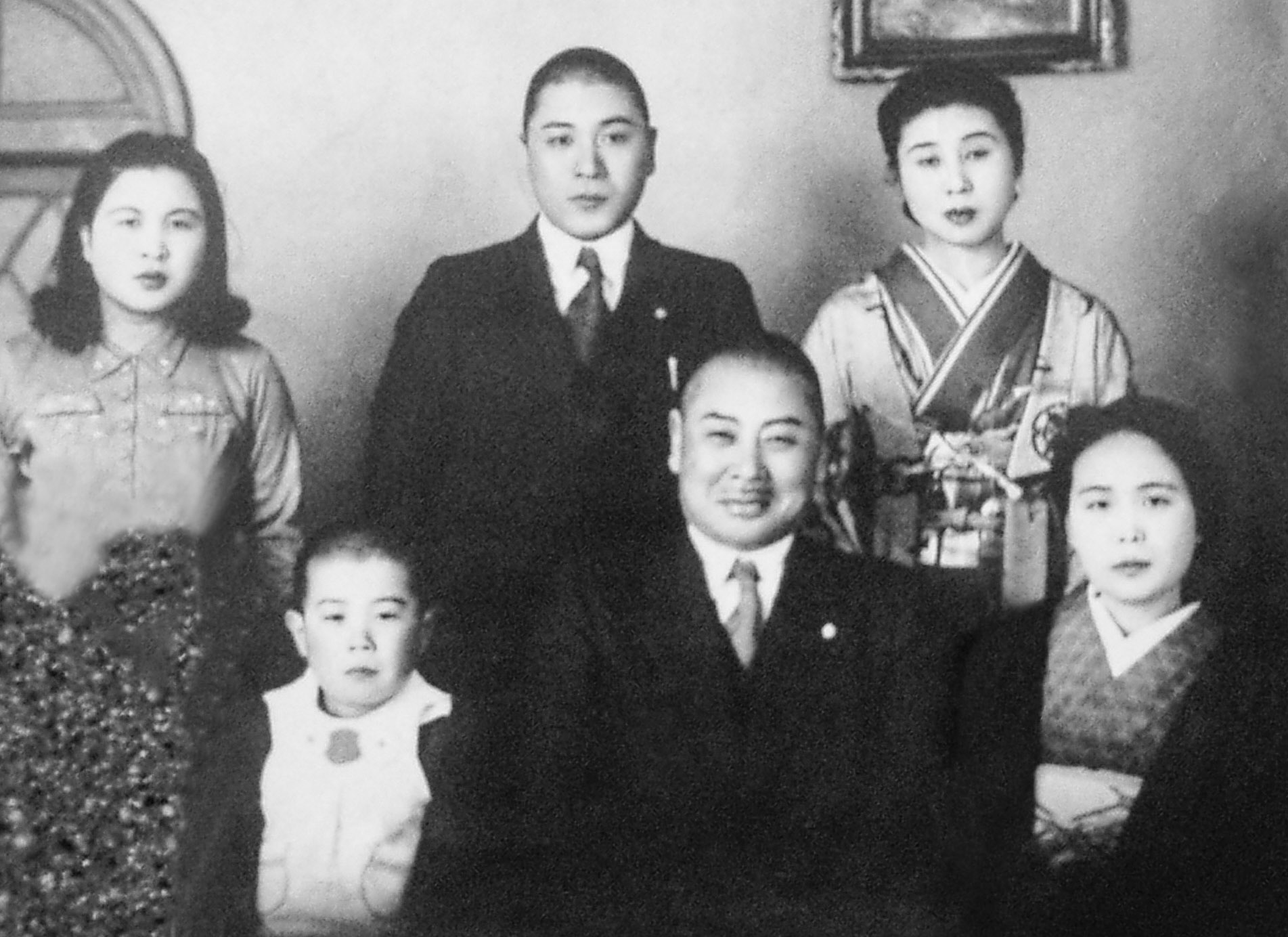

A photo of the Ishikawa family exists where Toshiko Ishikawa cut herself out of the picture because she felt guilty that she was the only one left alive. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathleen Burkinshaw)

My mom married my father (an American serving at an Air Force base near Tokyo) at the U.S. Embassy and moved to the U.S. in 1959. She was shocked by the prejudice that people still had against the Japanese. To avoid questions, she told everyone she was from Tokyo. She became a U.S. citizen a few years before I was born, and she “Americanized” the family home so that when I came along, no one would treat me the way she was initially treated (it happened anyway).

However, one picture had a place of honor in our home: It was a picture of my mom and her Papa. Every morning, she placed a fresh glass of cold water in front of the picture (because he, like so many others, had been thirsty from the heat of the atomic blast). This treasured photo was one of only six pictures she had from her childhood (stored somewhere not damaged by the atomic bomb). Any other pictures burned with her home on Aug. 6, 1945.

I was 11 the summer I realized her horrible nightmares that August also occurred in August the year before. I pestered her. She finally told me she was born in Hiroshima but lost her family, friends and home to the atomic bomb. She said it was too painful to discuss, and I couldn’t tell anyone.

It wasn’t until ninth grade when I read “Hiroshima” by John Hersey that I had an inkling of the horror in my mother’s nightmares. Shocked and horrified, I asked my mom if she experienced what was in the book. Without looking at the book, she said, “It was a hell that NO words could describe.” Again, I had to promise not to tell anyone — especially my teacher.

A beloved family photo, Toshiko Ishikawa at age 3 and her Papa. (Photo: Courtesy of Kathleen Burkinshaw)

When I was 31 years old, I spent a month in the hospital and was finally diagnosed with Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy (a neurological chronic, progressive pain disease affecting the sympathetic nervous system and the immune system). Doctors attributed my immune system deficiencies to the radiation my mother was exposed to from the atomic bomb.

Once home, I needed help taking care of myself, as well as my daughter, Sara (4 at the time), while my husband worked during the day. My parents came to help.

My life suddenly changed. I had to give up the successful career I had worked so hard to achieve. I worried that the pain would prevent me from being a good mom to my daughter. Despair and hopelessness crept in.

That’s when my mom began to share memories of Aug. 6 and the days afterward. She wanted me to know that she planned to commit suicide after she lost everyone she loved to the atomic bombing. But right before she jumped off the bridge, she heard her father’s voice when he would tell her stories of their samurai ancestors and how one should have pride and honor their family.

So, she didn’t jump, and now she was so glad because she had me and my daughter to love. She reminded me that the same samurai blood flowed through my veins so I would find strength and my own way.

It would be several years later when I would first speak publicly about my mother and Hiroshima. My daughter was in seventh grade and came home from school terribly upset. Her class finished the section on World War II, and kids were talking about that “cool mushroom cloud” picture. Would I tell her classmates about the people under that cloud — like her Grandma?

I called my mom, fully expecting her to say no. She surprised me and said yes. The students would be close to the age that she was when the bomb dropped, and maybe they could relate to her story. And as future voters, they’d leave that classroom knowing nuclear weapons should never be used again.

The following week, I spoke to my daughter’s class about the two coincidences that occurred on Monday, Aug. 6, 1945:

- My mom had been sick over the weekend. Her Papa let her stay home one more day to rest, but the next day, she would join her classmates, who were in the center of town taking down the wooden buildings (out of fear that fire bombs used on Tokyo would be dropped there). That kept her out of the center of town that day.

- Her Papa usually worked from home in the morning, then would head to his newspaper office in the afternoon. But that day, he left early to purchase a ticket at the train station for one of his employees. That would put her Papa in the center of town that day.

I would also discuss that after she clung to her friend screaming, my mother woke up covered in cement, wood and dirt from the houses around them. Her friend was no longer by her side, but she heard her crying.

My mom heard her stepmother calling to her, telling her to dig from underneath while she dug above her. When she finally climbed out, she noticed eerie shades of dark blue, brown and red in the sky. She glanced toward her home — it was gone, as were all of the houses on her street. In the distance, fire swirled around like small cyclones — right where her Papa was.

Digging out her friend was interrupted by black, sticky rain, which they thought was oil. The next thing my mother remembered was waking up to her stepmother telling her that they needed to look for her Papa.

The crumbled roads and lack of landmarks made travel difficult. While walking, my mother felt a tug on her arm, and she heard a small voice asking for help. When she turned, she saw some creature with a face melting like lava. She couldn’t tell if it was a boy or a girl, and she ran to her stepmother’s embrace. That memory forever haunted her nightmares. When they finally arrived at what was left of the station, Papa wasn’t there. My mother stayed hopeful, thinking he must be well enough to search for them.

My mother’s stepmother tripped, and when she looked down, it was Papa. He was unconscious, and he soon became one of the 80,000 people that died immediately or within hours of the bomb being dropped.

“I looked at his lifeless body, with his head the color of navy blue, swollen like a blowfish, but I didn’t see that man. Instead, I saw my beloved Papa, dressed in this handsome three-piece suit, Panama hat and shoes that he personally shined with great care. I didn’t see him on the funeral pyre. I saw him walking away proudly twirling his walking stick as he did when he walked me to school,” Toshiko Ishikawa once recalled.

I get very emotional discussing this moment with students. I can still hear my mother’s voice. And every time she talked about it, she cried as if it was happening all over again in front of her.

When teachers asked about a book, I called my mom to tell her about their request. Her only response, “Why would anyone care about a little girl in Hiroshima?” A few days later, I received a copy of that treasured photo of my mother with her Papa. I knew she also had happy, loving memories from her childhood. I decided to start writing a book.

It would begin almost a year before the atomic bomb dropped.

I decided I would write about Japanese daily life and culture, as well as the mindset of the people in Japan in 1944-45. I wanted readers to realize that Japanese children like my mom all loved their family, their friends, worried what might happen to them and wished for peace. All the same feelings/wishes of the Allied children.

I wrote “The Last Cherry Blossom” (a paperback version was released on Aug. 25) so that readers could witness the horror of that day through my mother’s 12-year-old eyes — something you would never get from two paragraphs and a mushroom cloud picture in a textbook.

My mom lived to be 82 years old. She wasn’t sick until the last few months of her life. During those months, I received my publishing contract. She placed it in front of her Papa’s picture and said to me, “Now I know why I lived when everyone I loved died. I couldn’t tell my story, but I had you, and you can do that for my Papa, my family.”

She never quite understood that I did it for her, too. I’m grateful that she also read a rough draft during that time because she died two months later in January 2015.

We honored her that summer in Hiroshima by adding her picture/story to the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for Atomic Bomb Victims and her name to the leather-bound books in the cenotaph at Peace Park.

“The Last Cherry Blossom” was published in 2016, and I’m humbled by the reception it has received. It’s now used in classrooms worldwide, including the Hiroshima International School, where it is required reading for its sixth-grade classes.

In 2018, “TLCB” became a United Nations Office of Disarmament Affairs Education Resource for Teachers and Students.

“The book’s powerful message raises awareness with the younger generation … especially pressing now that the hibakusha are getting older . . . a moving testament to why nuclear weapons should never be used again” said John Ennis, senior political affairs officer for the U.N. Disarmament Office.

In 2019, I had the opportunity to honor my mom and her story at the United Nations, as well as discuss with New York City teachers how to add nuclear disarmament to their curriculum alongside 2017 Nobel Peace Prize winners (under the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) and Setsuko Thurlow).

In a statement given after my presentation, Dr. Kathleen Sullivan, 2017 Nobel Peace Prize winner, said “. . . most atomic bomb survivors do not speak about their experience. It’s impossible to imagine. … We owe a great debt to you as we learn about these crude weapons … and what they do to us.”

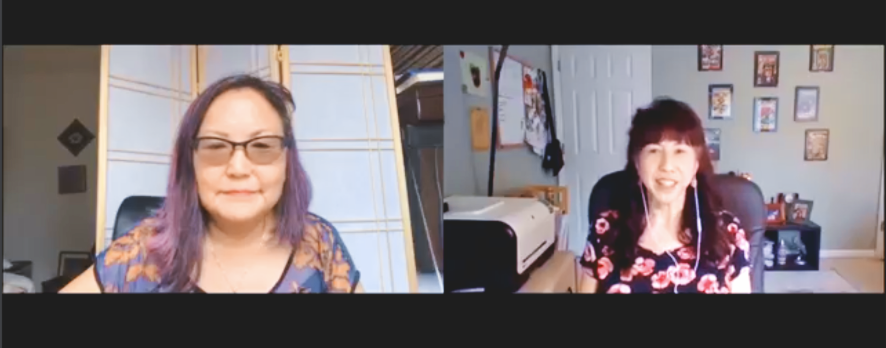

Naomi Hirahara and “The Last Cherry Blossom” author Kathleen Burkinshaw interacrt on Aug. 15 during the Japanese American National Museum’s virtual event “Daughters of Hibakusha Tell Hiroshima Stories.”

Recently, I had the privilege to honor my mother and atomic bomb victims at the following events for the 75th commemoration: May Peace Prevail on Earth, Ribbon International 2020 and #StillHere Hiroshima Nagasaki 75 National Event. And on Aug. 15, award-winning author and friend Naomi Hirahara and I spoke at the Japanese American National Museum’s virtual event “Daughters of Hibakusha Tell Hiroshima Stories.”

Hibakusha stories cannot die with them. Statistics about and treaties to eliminate nuclear weapons are extremely important. However, in order for future voters/voters to genuinely care about those statistics/treaties, they need to make that connection with the humanity under those famous mushroom clouds, so that the same deadly mistakes are not repeated.

My mother was the bravest person I will ever know. I’m honored that she entrusted my daughter and me with her memories and her heart. As second- and third-generation hibakusha, we will continue to tell her story. Her voice mattered then, and it matters now and always.