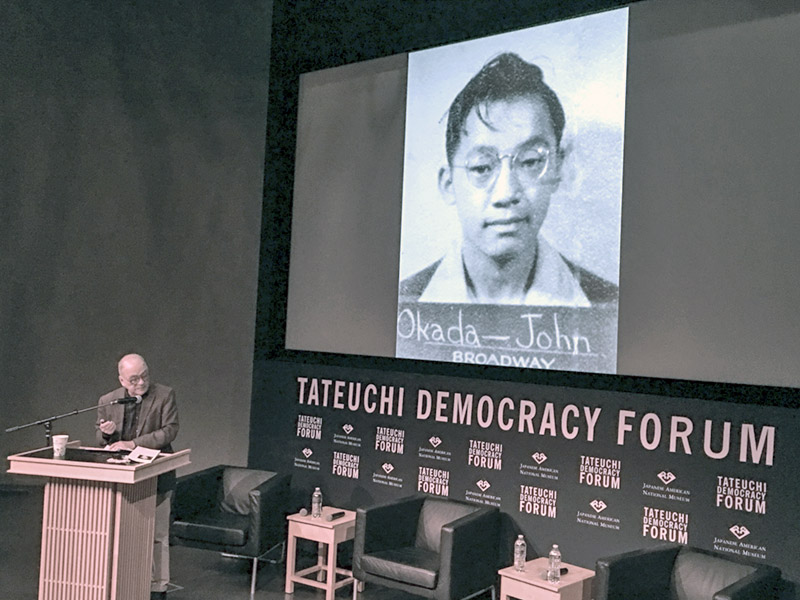

Co-editor Frank Abe, left, holds up an older copy of John Okada’s seminal novel “No-No Boy” during the Feb. 2 discussion on a new book about the author as moderator Brian Niiya and co-editor Greg Robinson look on. (Pacific Citizen photo)

Book’s editors discuss the backstory behind 1957’s ‘No-No Boy.’

By P.C. Staff

In “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” the titular on-the-run-from-the-law characters ask over and over again about their dogged pursuers the question, “Who are those guys?”

For a generation of Asian American writers, scholars, historians and fans of literature wowed by “No-No Boy” and its elusive Nisei author John Okada, it was those pursuers who asked, “Who was this guy?”

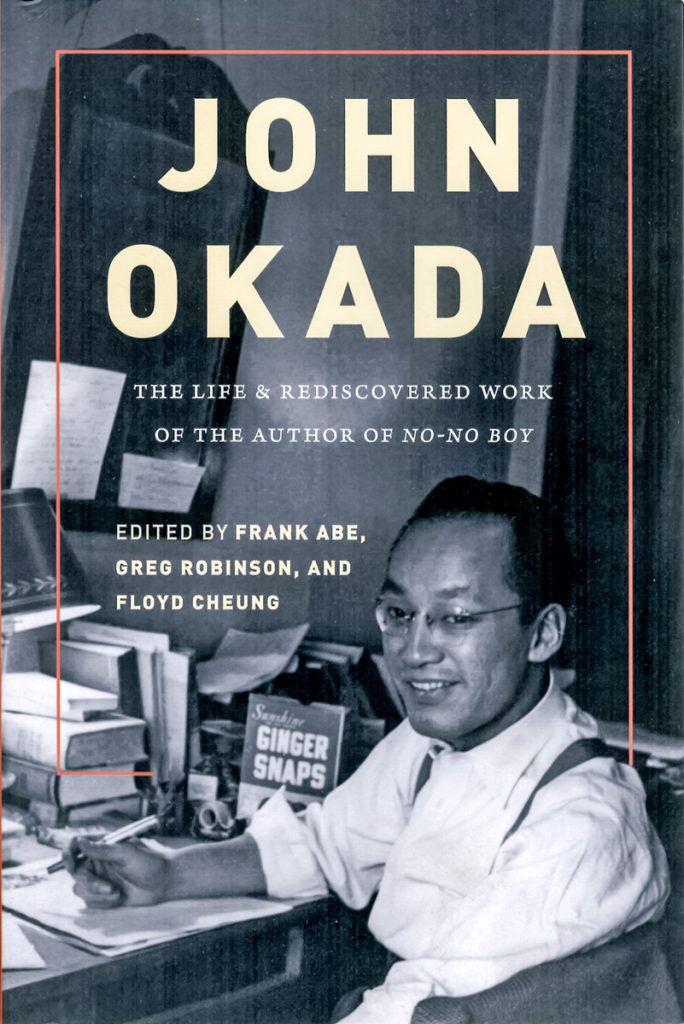

Answers about who Okada was, his “lost” writings and the continuing impact and import of his one and only novel were presented on a recent, rainy Saturday in Little Tokyo at a Japanese American National Museum-sponsored event on Feb. 2 featuring Frank Abe and Greg Robinson, who along with Floyd Cheung, edited the recently published “John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of ‘No-No Boy.’”

Also present were many University of California, Los Angeles, students and Okada’s two offspring, Dorothea and Matthew, and discussion moderator Brian Niiya, content director at Denshō.

***

For years, little was known about the author of 1957’s “No-No Boy,” published originally by the Charles E. Tuttle Co. — and that only fueled the mystique surrounding him. While not a flop, the Seattle-set novel about a Japanese American draft resister named Ichiro in the resettlement years following World War II failed to, according to Robinson, a history professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal, connect in a big way with its intended audience: Japanese Americans.

While some cooked up conspiracy theories to explain the novel’s initial muted response, others came to later believe, more plausibly, that it was a matter of timing, with the painful memories of forced evacuation and incarceration still too raw to be explored in literature.

Within about a decade and a half, however, “No-No Boy” was rediscovered by a younger generation of Asian American writers in search of role models from the previous generation who didn’t write sanitized, bowdlerized and committee-approved model-minority stories.

Those Asian American writers who came of age in the late 1960s and early 1970s — among them Jeffery Chan, Frank Chin, Lawson Inada and Shawn Wong — who had rediscovered Okada’s “No-No Boy” wanted more.

But there was “no-no” more. Okada’s one novel, it seemed, was it.

Had Okada been silenced by a conservative Japanese American establishment that didn’t like his writing style or his sympathetic take on those who chose not to serve their country? Was he an embittered expat in exile who wanted nothing more to do with America? Was he buried in a pauper’s grave after having committed suicide, thwarted by his lack of success?

Who was this guy, indeed.

Those then-young writers who had rediscovered Okada started digging, only to learn that their hero had died already in 1971 at 47 — and then were shocked to learn that his widow, Dorothy Okada, who they tracked down and interviewed, had incinerated, along with photos and letters, the manuscript for the second novel her late husband had been writing!

But thanks to their rediscovery of John Okada, they were able to reprint and reintroduce “No-No Boy” to subsequent generations — and the reverberations from that continue to this day, with the novel, in all its different iterations, having sold more than 200,000 copies since 1957, such that “No-No Boy” has “spawned a cottage industry in graduate-student theses and dissertations,” said Abe, visiting Los Angeles from Seattle.

It also led to the new book, published in July 2018 by the University of Washington Press, that would take more than 10 years to complete, from the time Abe and Robinson met in early 2007 at dinner party in Seattle, hosted by mutual friend Chizu Omori, sparked by a mutual interest in Okada.

One of the outcomes of that continuing fascination with Okada was Robinson’s discovery in different Nikkei community English-language newspapers more writings by none other than Okada.

According to Robinson, his discovery in microfilmed editions of the Northwest Times of a one-act play and several short stories by Okada left Abe in a state of amazement. He recalled Abe saying, “Okada scholars are going to go nuts when they hear this!”

Robinson also found in a Toronto Japanese Canadian newspaper called the Continental Times the full 1957 “No-No Boy” review, the long-missing source for an excerpt that was used in the CARP (Combined Asian American Resources Project) reprint. Citing the “wonders of for-pay databases,” Robinson also found other unknown works, such as Okada’s piece on wasteful spending by a defense contractor that appeared in Armed Forces Management in 1961.

It was, it seemed, time to compile the new writings found by Robinson, the biographical material compiled by Abe and combine that into a new book along with literary analysis by Cheung, an English-language professor at Smith College who was also a fan of Okada.

More than 10 years in the making, “John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of ‘No-No Boy’” finally became a reality in 2018.

It took years, but “John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of ‘No-No Boy’” finally became a reality in 2018.

The new book would print everything “new” written by Okada, but also serve to disabuse urban legends that a certain Japanese American civil rights organization had tried to supress “No-No Boy” or even boycott the book.

“The evidence shows that Bill Hosokawa, who was the voice of JACL in the Pacific Citizen … wrote a review of ‘No-No Boy,’” Abe said, and in it praised Okada as a writer of promise who might someday write the great Nisei novel. “I maintain he did,” said Abe.

So — who was John Okada? It turns out he was neither a so-called No-No Boy or a resister of conscience, but, in fact, an Army veteran who served as a linguist during WWII for the Military Intelligence Service and went to Guam and post-war Japan’s occupation period.

***

According to Robinson, Okada was an empathetic writer in many disciplines: poetry, short stories, satirical essays, parodies, plays and technical writing. What was most surprising to Abe, however, was learning that later in life Okada had worked in advertising.

Said Abe: “John Okada was a chain-smoking, 1960s Nisei ‘Mad Man,’ who may have written ad copy for products like Tide detergent and Gleem toothpaste.” Or, as he later put it, Okada was a “Nisei Everyman,” who followed the “study hard, work hard, raise a family” ethos — a typical Nisei father who died too young.

How an Army vet like Okada came to write a book with a draft resister protagonist was also fascinating.

According to Abe, following Japan’s Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor, Okada’s father, Yoshito, was among the group of Seattle’s many Issei men rounded up by the FBI for suspicion of possibly being disloyal to the U.S. and therefore separated from their families. Soon, like other Japanese American families from the area, the remaining members of the Okada family were sent to Camp Harmony, aka the Puyallup Assembly Center.

There, in what may have been up to that time his most important writing assignment, Okada wrote a letter to William Collins, a boarder at the hotel operated by Okada’s parents. In that letter, he asked Collins to write a letter to Attorney General Francis Biddle vouching for his father’s good character, in the hope of having him released early. Collins did so, and six other hotel residents signed it. It worked. Okada’s father was released.

Okada’s family would be sent to a concentration camp, but he only spent three weeks at Idaho’s Minidoka WRA Center — he was among of group of young Japanese Americans released to attend Scottsbluff Junior College in Nebraska. From there, he and some friends enlisted to serve in the MIS, to be trained at Camp Savage, Minn.

After the war, Okada used the GI Bill and enrolled at the University of Washington to pursue his interest in writing. What he needed, though, was a story that mattered for him to write about.

“That changes when a guy he knew from Broadway High School, Hajime ‘Jim’ Akutsu, is released from federal prison,” said Abe. “Jim Akutsu had resisted the draft at Minidoka. He was convicted of draft evasion and like Ichiro (the protagonist in ‘No-No Boy’) had spent two years in federal penitentiary on McNeil Island.”

They reconnected, and though their wartime experiences were different, they became friends and drinking buddies, along with some other Nisei draft resisters.

Okada learned that Akutsu’s father had also been arrested the same night as his father had been and separated from his family. Unlike Okada’s father, who was released relatively quickly, Akutsu’s father was held at a Justice Department camp much longer.

“He’s finally released back to Minidoka after two years, and both father and son had changed so much that neither recognized the other,” Abe said.

During those nights at places like the Wah Mee Club, Okada learned about what Akutsu and other Nisei draft resisters had endured.

He asked questions and took notes.

For the empathetic Okada, the seed of what would become “No-No Boy” was planted.

***

During the event’s Q & A, an audience member said she loved “No-No Boy” but questioned why the book had that title, which she called misleading and probably led to misunderstandings about who the no-no boys were and who the draft resisters were — and she wondered why Okada gave such an incorrect title for his novel.

Frank Abe, one of three co-editors of “John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of ‘No-No Boy,’ ” discusses Okada’s life and his inspiration for writing his 1957 novel. (Pacific Citizen photo)

Abe responded, “John Okada did a little bit of a disservice to the Nisei draft resisters because the conflation of the no-no boys and the draft resisters is something that started with the publication of ‘No-No Boy.’ No-no boys and draft resisters are two distinct groups.”

He went on to give context to the 1943 loyalty oath administered by camp officials that included Questions 27 — which asked whether one would serve in the military — and 28 — which asked for full allegiance to the United States and to forswear allegiance to Japan’s emperor.

“Those who answered ‘no’ to both of those questions, whether because they believed it or were protesting, were segregated from the others and sent to the Tule Lake segregation center,” Abe said, explaining further that the draft resisters were those who a year later in 1944 protested by refusing the military draft so as to get a court case to contest the legality of eviction and incarceration.

“Jim Akutsu was a draft resister, and Ichiro Yamada in the novel … was a draft resister,” Abe added. The title character in “No-No Boy,” in other words, was not a no-no boy. Then, Robinson put forward a theory that Okada had nothing to do with naming the book.

“Very often, the publisher decides on the title, and since John Okada did not propose a title for the novel in his pitch letter to Tuttle, it’s very probable — not certain — that it was Tuttle’s initiative to call it ‘No-No Boy,’” said Robinson.

As the event wrapped up, Abe told the audience he was working with Cheung on collecting and translating the Japanese-language writings of Issei who were incarcerated during the war.

With the publication of “John Okada: The Life & Rediscovered Work of the Author of ‘No-No Boy,” someone asked what would happen if more writings of Okada’s works should turn up. While the odds of that happening are slim, Abe said he’d be happy to publish any additional writing by Okada on his blog, resisters.com.

For now, however, the saga of John Okada is a closed book.