The five-hourlong docuseries looks back while mapping hope for the future.

By P.C. Staff

Recent news reports of Asians in the U.S. having been spat and coughed upon, as well as verbally and physically assaulted since the outbreak on these shores of the novel coronavirus — which has also been referred to by high-ranking federal government officials as the “Chinese virus,” the “Wuhan virus” and “kung flu” — are alarming and shocking, yet completely unsurprising.

That so many of those on the front lines and in laboratories — nurses, physicians and scientists — in the U.S. involved in the struggle to save and care for those fighting for their lives against COVID-19, as well as find a cure for it, are also of Asian heritage is heartening and inspiring — and again, completely unsurprising.

During PBS’ “Asian Americans” session at the Television Critics Association Winter Press Tour in Pasadena, Calif., on Jan. 10, narrator Tamlyn Tomita (second from left); comedian and featured participant Han Kondabolu; producer Renee Tajima- Peña (left); and producer/director Grace Lee discussed the new five-part series, which examines what the 2010 U.S. Census identifies as the fastest-growing racial/ethnic group in the U.S. Told through individual lives and personal histories, “Asian Americans” explores the impact of this group on the country’s past, present and future. (Photo: Rahoul Ghose/PBS)

It’s one of the takeaways one could have after viewing the new PBS docuseries “Asian Americans,” airing nationwide in May, which not coincidentally is also Asian Pacific American Heritage Month.

In other words, “Asian Americans” encapsulates the seemingly eternal yin and yang of how Asians in America are perceived and treated — often simultaneously —between the extremes and variations of “yellow peril” and “model minority.”

Clocking in at nearly five hours, with the first two episodes (“Breaking Ground,” “A Question of Loyalty”) airing on May 11 at 8-9 p.m. and 9-10 p.m., and the final three episodes (“Good Americans,” “Generation Rising,” “Breaking Through”) airing the next night from 8-11 p.m., “Asian Americans” takes on the daunting task of telling the story — stories, actually — of a diverse group of Americans, would-be Americans and future Americans whose forebears came here neither willingly from Europe nor unwillingly from Africa but from different parts of Asia, for reasons that nevertheless parallel those other American groups: hope for a better life or as exploitable labor.

Telling that overarching story of Asians in America in just five hours is no easy task — but “Asian Americans” gives it the ol’ college try. On that note, even those who majored in Asian American studies (see episode 4 and be grateful that such courses can now be taken with relative ease) should find it of much interest and learn something new, fascinating or ironic from the five hours, with enough fodder to inspire future generations of filmmakers.

A milestone production of WETA Washington, D.C., and the Center for Asian American Media in association with the Independent Television Service, Flash Cuts and Tajima-Peña Productions, “Asian Americans” features narration by actors Daniel Dae Kim and Tamlyn Tomita, with individual episodes directed by S. Leo Chiang, Geeta Gandbhir and Grace Lee. The series’ producer is Renee Tajima-Peña.

Tajima-Peña also happens to be a professor at the University of California Los Angeles’ Asian American Studies Dept., the holder of the Alumni and Friends of Japanese American Ancestry Endowed Chair and the director of the UCLA Center for EthnoCommunications in the Asian American Studies Center.

“I’m kind of the new Bob,” she joked, a reference to her predecessor, pioneering filmmaker Robert Nakamura, who founded the Center for EthnoCommunications in 1996 and retired in 2011. Tajima-Peña took over in 2012.

As for the process used to choose which stories to tell, Tajima-Peña told the Pacific Citizen, “One thing that I didn’t want to do is go back to ‘the first Asian who landed on U.S. shores.’ It’s hard to say who that was, for one thing. It’s television. I really wanted to tell stories that were alive, where you can find descendants, where there are images and, hopefully, footage.

“So, we decided to start when the first bigger waves of immigrants started to come,” Tajima-Peña continued. “They were Chinese and then Japanese, South Asian — you can’t really call Filipinos immigrants, they were colonized subjects — but they started also to arrive.”

It’s fitting, perhaps, that Episode 1 — “Breaking Ground” — begins with a Filipino man named Antero Cabrera, whose arrival to the U.S. coincides with 1904’s St. Louis World’s Fair, just a few short years after the U.S.’ 1898 annexation and colonization of the Philippines following Spain’s loss in the Spanish-American War.

At the fair’s Philippine Exhibition, Cabrera is hired to portray a loincloth-wearing Igorot “savage,” despite having been educated by missionaries. He nevertheless manages to capitalize on the opportunity for his own gain.

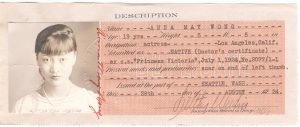

Actress Anna May Wong’s certificate of identity photo. (Photo: Courtesy of the National Archives)

The episode also covers Chinese railroad workers who are infamously excluded from the photo taken at Promontory Point, Utah, to mark when east and west tracks met; the complicated quest for citizenship and legal recognition by East Asian and South Asian immigrants; and the short-lived rise of matinee idols Anna Mae Wong and Sessue Hayakawa. (Later in the series, there’s another Hayakawa — S. I. — who acts in a way that makes him a hero to some and a zero to others, depending on one’s political perspective.)

“A Question of Loyalty” begins with Satsuki Ina telling her Japanese American family’s trauma of dehumanization thanks to Executive Order 9066, as well as the story of the Korean American Anh family, in particular, Navy veteran Susan Anh Cuddy and her brother, actor Phillip Anh, and their father, who was Korean independence martyr Ahn Chang-ho, aka Dosan.

George Uno peruses a family photo album.

The episode’s centerpiece, though, is the story of the Uno family of Utah. With 10 children, the Uno offspring includes Military Intelligence Service and 442nd RCT vets and activists Amy Uno and Edison Uno, who would become known as the father of the redress movement. But it’s eldest brother Buddy Uno’s tale, because of expectations dashed by racism, that is the most compelling and tragic.

In Episode 3, titled “Good Americans,” WWII is shown as a turning point for Asian American acceptance. Following the stellar service by Japanese American 442nd veterans, America’s lofty but unrealized notion of equal treatment under the law cannot be denied, and politics become the vehicle by which figures such as Hiram Fong, Daniel Inouye, Patsy Mink and Dalip Singh Saund push boundaries, effect change and even help gain statehood for Hawaii. More whimsically, even American motherhood gets an Asian face when Toy Len Goon gets named 1952’s “Mother of the Year.”

It’s in Episode 4, titled “Generation Rising,” which looks back mostly at the 1960s, when things begin to get interesting for Asians in America, including the roots of the grape boycott most Americans associate with Cesar Chavez and Mexican farm laborers, even though it actually began with Filipino farm laborers led by Larry Itliong.

It’s also the decade of the Vietnam War, with some Asian American vets questioning their personal — and America’s — participation in it. Related to that is the rise of the civil rights movement and ethnic studies overall, as well as the birth of the term “Asian American” in particular.

Laureen Chew, SFSU 1968 strike organizer (Photo: PBS)

But the biggest change with long-term ramifications comes in the form of 1965’s reforms in immigration laws that open the door to more emigration from Asia, which manifest in the 1980s when foreign-born Asians begin to outnumber American-born Asians — and that leads to the final installment, titled “Breaking Through,” which shows how events of the 1980s and ’90s would map the trajectory to the present day.

Newer Asian immigrant groups from Southeast Asia who arrived after the U.S. defeat in Vietnam begin to make an impact. Japan-bashing leads to the murder of Vincent Chin and a mockery of justice for his killers.

“Asian Americans” shows how that tragedy leads to necessary changes in the definition of what constitutes a hate crime. Another success comes a few years later with the culmination of the Japanese American redress movement.

The final installment also documents the coming of age for Korean immigrants, who bear the brunt of the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Existing black-Korean tensions, exacerbated by Latasha Harlins’ slaying by liquor store owner Soon Ja Du, are fuel for the conflagration that follows the Rodney King verdict.

But it’s also, of course, about the same time as comedian Margaret Cho’s breakthrough ABC sitcom “All American Girl,” and the critical and commercial success of “The Joy Luck Club” novel and 1993 movie. Yin and yang yet again.

And, speaking of yang, there’s also Jerry Yang, who co-founds Yahoo! and comes to personify those educated and elite Asian Americans in high tech, even as less-educated, less-fortunate Asian immigrants do the piece-work on Silicon Valley’s assembly lines.

The arrival of “Asian Americans” during the coronavirus lockdown might actually be fortuitous in the long run. With “business as usual” on indefinite hold, this documentary turns out to be timed just right for the necessary reflection on where this vibrant and vital group of Americans has been — and where it, the nation and the world will need to travel.

◊◊◊

A Conversation With Renee Tajima-Peña

The producer of the PBS docuseries ‘Asian Americans’ talks about the ‘breadth and diversity of the Asian American experience.’

Pacific Citizen: How many years did it take once the series was greenlighted to complete it, and when did official production begin and end?

Renee Tajima-Peña: It was greenlit in the spring of 2018. We had done preliminary research and treatments before that, like in the fundraising process, but we started preproduction, research and production around August of 2018.

So, it was done really quickly. … It’s five hours, lots of stories, filming all over. There was a big shoot that Grace Lee did in Japan. She got to shoot in Hawaii and Japan.

P.C.: What was the process used in choosing which stories to tell, what to include, what to exclude, who to focus on?

Renee Tajima-Peña

Tajima-Peña: That started in the treatment-writing-research-fundraising phase. … We were able to find people that had some kind of personal connection, in addition to scholars. Even our scholars had personal connections. Erika Lee and Gordon Chang, their families came to the United States in the 1800s. … Because it’s television, we wanted to make a series that was focused on character, drama, stories and personal experiences. …

We knew that it was never going to be about every single Asian nationality. It couldn’t be [if we were] to make it a coherent and dramatic story with arcs. We had to pare it down, but at the same time, we wanted to show the breadth and diversity of the Asian American experience.

That’s why people are really shocked that in the first episode, which is the late 1800s, early 1900s, everybody expected, “Well, it’s just going to be about the Chinese and the Japanese” — but it’s also about Filipinos, and it’s also about South Asians. We thought that it was really important to start the series with that breadth of the Asian American experience.

P.C.: Was there a topic or person that all the filmmakers, yourself included, wish you could have included but could not?

Tajima-Peña: We did have a lot of stories that we could not actually film or we couldn’t get into the cut.

Was there a story that I wish I told? Well, you know, we were hoping to do six episodes, so we could have had more post-1965 stories. We just didn’t have the money for it.

I would not have done really recent stories because every time we would think about more recent stories, it just felt like public affairs. The beauty of history is that you have time to really reflect on what happened in the past. It’s hard to reflect on what happened last year.

P.C.: What about sports?

Tajima-Peña: Oh yeah, you know, I wish that was something I would have done.

There are a lot of great stories.

P.C.: What do you think will be the most-revelatory aspect to this series for Asian American audiences?

Tajima-Peña: I think even for Asian American audiences there’s this real immovable image of Asian Americans as being this model minority, and that’s a myth. Of course, there are Asian Americans who have done well, but if you look in the series, it really looks at where that myth came from and how it’s been used. I think we also shift what it means to be a success in America.

We have people who, against all odds, took their cases to the Supreme Court. In the 1800s, a Chinese restaurant worker, Wong Kim Ark, who was born in San Francisco. When he was denied re-entry into the United States, he said, “No. I’m Chinese, but I’m a citizen,” and he went to the U.S. Supreme Court. That, to me, is amazing. That’s why my parents are American citizens because of Wong Kim Ark and birthright citizenship. Their parents were immigrants, aliens ineligible for citizenship.

You’ve got Patsy Mink. There were no women of color in Congress. It was an impossible dream when she ran in 1964 and was elected. She was the first. To me, those are success stories.

(Note: Prior to the debut of “Asian Americans” on PBS will be “Digital Town Hall — Asian Americans in the Time of COVID-19,” scheduled to take place on April 30 at 8-9 p.m. ET/5-6 p.m. PT on Facebook Live by CAAM. It will explore how today’s discrimination directed at Asian Americans is rooted in a long history of xenophobia and racism from the mid-19th century to the present. The event page for the Town Hall on Facebook is: facebook.com/events/578222596150318/)

◊◊◊

Asian Americans

PBS (check local listings for airtimes)

(pbs.org/weta/asian-americans/)

May 11: 8-9 p.m. and 9-10 p.m.

‘Breaking Ground’: In an era of exclusion and U.S. empire, new immigrants arrive from China, India, Japan, the Philippines and beyond. Barred by anti-Asian laws, they become America’s first “undocumented immigrants,” yet they build railroads, dazzle on the silver screen and take their fight for equality to the U.S. Supreme Court.

‘A Question of Loyalty’: An American-born generation straddles their country of birth and their parents’ homelands in Asia. Those loyalties are tested during World War II, when families are imprisoned in detention camps, and brothers find themselves on opposite sides of the battle lines.

May 12, 8-9 p.m., 9-10 p.m. and 10-11 p.m.

‘Good Americans’: During the Cold War years, Asian Americans are simultaneously heralded as a model minority and targeted as the perpetual foreigner. It is also a time of bold ambition, as Asian Americans aspire for the first time to national political office, and a coming culture-quake simmers beneath the surface.

‘Generation Rising’: During a time of war and social tumult, a young generation fights for equality in the fields, on campuses and in the culture, as well as claim a new identity: Asian Americans. The war’s aftermath brings new immigrants and refugees who expand the population and the definition of Asian America.

‘Breaking Through’: At the turn of the new millennium, the country tackles conflicts over immigration, race, economic disparity and a shifting world order. A new generation of Asian Americans is empowered by growing numbers and rising influence but faces a reckoning of what it means to be an American in an increasingly polarized society.

Note: After being aired, episodes will be available to stream at PBS.org.

Executive producers: Jeff Bieber and Dalton Delan for WETA; Stephen Gong and Donald Young for CAAM; Sally Jo Fifer for ITVS; and Jean Tsien. Flash Cuts producer: Eurie Chung. Consulting producer: Mark Jonathan Harris.

Major funding for “Asian Americans” is provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation, PBS, the Ford Foundation/JustFilms, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Freeman Foundation, the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, Carnegie Corp. of New York, the Kay Family Foundation, the Long Family Foundation, Spring Wang and California Humanities.