In August at the weekend-long “Unite the Right” rally, white nationalists descended onto Charlottesville, Va., thrusting into the national spotlight a reality that many communities of color know to be true: White supremacy is alive and well in the United States.

With the exception of a few groups of Ku Klux Klan or neo-Nazis openly wearing their regalia, the majority of the mostly white, mostly male demonstrators came dressed wearing polo shirts and slacks, looking like neighbors we pass in the street on a daily basis. Marching through the moonlit University of Virginia campus hoisting torches amidst chants of “blood and soil” and “Jews will not replace us,” this could have easily been mistaken for the start of a Nazi-era pogrom.

For much of the last 50 years, white nationalists have been referred to as “fringe hate groups,” described using similarly innocuous language that minimizes the impact of white supremacy and erroneously suggests that only a small minority of Americans share these hateful sentiments.

However, when the president of the United States responds to the vehicular homicide of Heather Heyer by a white nationalist in a statement calling out the “egregious display of hatred, bigotry and violence, on many sides,” we as Americans must confront the reality of our nation’s racial hierarchy.

While overt racism was somewhat less frequent until the recent shift in political climate, much of the institutional bias and systemic racism from the pre-civil rights era remains a daily reality for many communities of color. To understand the full extent of racial power dynamics in this country, we must remember how the legacy of European imperialism impacted the manner in which this country was founded as a settler-colonial state.

A couple hundred years before our country was founded, European empires began the systematic subjugation of nonwhite peoples across the globe. In the Americas, this was made possible through the enslavement of Africans and mass genocide of Indigenous peoples. To justify the horrors that European states and their agents were inflicting upon the peoples of the nonwhite world, social and pseudoscientific distinctions were made between Europeans as superior and nonwhites as inferior, subhuman beings.

As the first empire to encompass all regions of the world by the 17th century, the Spanish developed “Las Castas” or the castes, a hierarchal system of racial classification based on parentage designed to maintain Spanish superiority in colonial societies. The ethnically Spanish raised in the Iberian Peninsula with the lightest skin are valued the highest, while the mixed off-spring of African and Indigenous peoples with darkest skin are valued the least. Varying degrees of opportunity related to class status were attributed according to an individual’s rank within this hierarchy.

While the British holdings in the Americas did not dogmatize their racial hierarchy to this extent, the Indian Wars and African Slave Trade created a clear foundation for institutional racism to exist within the U.S. Bear in mind that the U.S. Constitution as originally drafted only extended its Bill of Rights to “free white men.” The Naturalization Act of 1790 further clarified that only “any alien, being a free white person” was eligible for U.S. citizenship.

As European empires continued their conquest of Africa and Asia, and the U.S. completed its westward expansion in the 19th century, scientific racism was used to further support the theory of white supremacy. Often associated with pseudoscientific fields such as phrenology (the measure of one’s skull in relation to specific personality traits), scientific racism used selective data to try and prove the hypothesis of European racial superiority.

Aside from the scientific justifications of white supremacy, colonization became morally defensible under the guise of bringing civilization and oftentimes religious salvation to these less-fortunate nonwhites. The overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1893 by Christian missionaries and U.S. business interests is a particularly good example.

Public support for formal annexation in 1898 was garnered under the guise of modernizing the islands, while emphasizing the economic and militarily strategic benefits to the U.S. government.

The same year that Hawaii formally became a U.S. Territory, the Spanish-American War resulted in the U.S. gaining three additional overseas possessions (Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico), and the U.S. officially became an imperial power. In political satire magazines of the era, Uncle Sam was shown with his new colonial possessions, each a racial caricature associating Filipinos, Native Hawaiians and Puerto Ricans with blackness or indigenousness. Although satirical in nature, these images clearly established their pecking order within the racial hierarchy.

It should be noted that the Philippines was also a special case in that unlike Guam and Puerto Rico, which were both peacefully transitioned to U.S. colonial administration, the Filipinos unsuccessfully fought a war of independence with the U.S. until 1902. The portrayals of Filipino Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo almost always associate him and other Filipinos with blackness. White supremacy was thus used to uphold the status quo of U.S. imperialism over its nonwhite territorial subjects.

By the beginning of the 20th century, an influx in immigration by America’s new colonial subjects, in addition to the growing Chinese and Japanese American communities, caused a new type of racial issue. Threatened by cheap labor and unable to compete with collective community investment by Chinese and Japanese immigrants, white nativists of California and elsewhere in the Western states turned on the nonwhite, nonblack immigrants.

As daily newspapers competed to build circulation, sensationalist headlines about the yellow peril became an easy way to sell paper subscriptions. A popular phrase in political satire magazines of the late-19th century, “yellow peril” was a term used to describe the supposed threat that Chinese immigrants posed to the economic and moral welfare of American society.

Largely because of the yellow peril coverage, public support swung in favor of passing the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, to this day the only piece of U.S. immigration legislation to target a specific ethnic group in its passage. It is also worth mentioning that the later circulation wars between newspaper tycoons Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst had a direct impact in garnering public support for the Spanish-American War and resulting territorial acquisitions in 1898.

In addition to the yellow press, the influential writings of two white supremacist authors from New England had a major impact on the reversion toward white nativism during this era. Madison Grant was a Yale graduate and Columbia University-educated lawyer and eugenicist who authored “The Passing of the Great Race.”

This 1916 book used pseudoscience to argue that the so-called Nordic races of Scandinavia were the most superior of all Europeans, based on the idea that Southern and Eastern Europeans had been tainted by intermarriage with nonwhite peoples in their ancient histories. Emboldened by his Nordic theory, Grant began lobbying for stricter immigration policies and anti-miscegenation laws to maintain racial purity. As a close friend of presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover, some of Grant’s statistics were even used to justify the Immigration Act of 1924.

Another Ivy League alumni from Harvard named Lothrop Stoddard further expanded the writings of Grant in his 1920 book “The Rising Tide of Color: The Threat Against White World Supremacy.”

Stoddard argued that European whites would soon be overrun by people of color from the lands they had colonized. He further suggested that for the U.S. to remain a white-dominated society, stricter immigration legislation needed to be enacted.

Stoddard’s enduring legacy is having directly influenced the Nazi Party’s racial theorist Alfred Rosenberg through his 1922 book “The Revolt Against Civilization: The Menace of the Under-man.” While it is likely that Nazism would have existed regardless, the exact nature of the Aryan racial supremacy theory can be credited in part to this American author. In his brief later stint as an overseas news reporter stationed in Nazi Germany, Stoddard would enjoy special privileges that his other American counterparts did not.

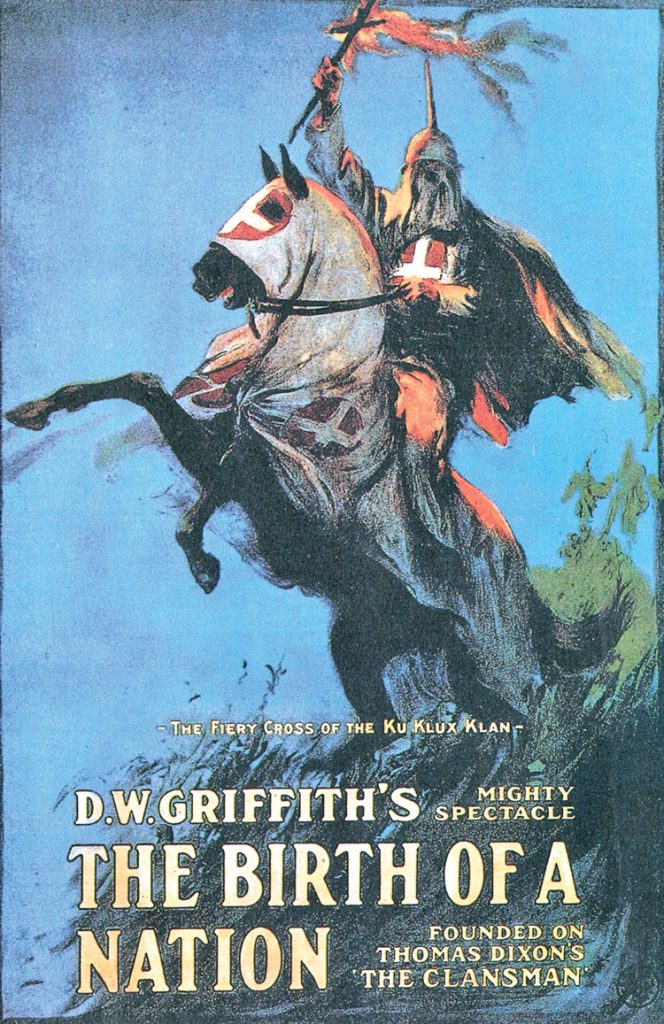

Stoddard was also openly affiliated to the Ku Klux Klan. The original KKK were part of an active insurgency against Union rule and were quickly put down by the federal government within the first five years of post-Civil War Reconstruction in 1871. The second generation, to which Stoddard belonged, regained popularity through D. W. Griffith’s 1915 film “The Birth of a Nation,” which dramatized the Reconstruction Era Klan as saviors to white America. The film is also known for having been the first American motion picture screened at the White House during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency.

At its peak in 1924, Klan membership rose to nearly 5 million people, with chapters in almost every state. Unsurprisingly, this date also coincides with the Immigration Act of 1924 that ultimately halted immigration from Asia and the Middle East and dramatically reduced the numbers of European immigrants allowed into the country.

Through a combination of regressive nativist policy regarding immigration and the structural racism exacerbated by U.S. imperialism in Asia Pacific, the U.S. as a whole became less tolerant of diversity from the mid-1920s until the civil rights era. There are still many aspects of institutional racism that keeps white supremacy as a structural truth in the U.S.

Additionally, there are several alarming parallels between the 1920s and today, including the immigrant scapegoating and anti-blackness (or anti-diversity of any kind) brought about by a populist president whose constituent base includes a sizeable population of white nationalists.

We do not choose the circumstances in which we are born under, nor the era into which we must live. It took 500 years for Amer-European imperialism to run its course, and we are currently living through the very early days of the restorative justice of decolonization in the post-colonial world. We must continue fighting white supremacy in all its forms. If we do not, history may very well come to repeat itself.

Rob Buscher is a member of the JACL Philadelphia Chapter board of directors.