By Lynda Lin Grigsby, Contributor

I balked when Pacific Citizen Executive Editor Allison Haramoto invited me to write for this year’s Holiday Issue. What could I possibly say? A decade ago, I served as this newspaper’s assistant editor, and after a hiatus, joyfully started writing here again last year. I have filled pages with community news that I hope have enriched your lives. At the end of the year, I feel deeply that the Holiday Issue belongs to you, the readers. Because you read my writing in many other issues, I wanted to cede my space for your words. With help from JACL staffers, I put out a call for pitches with the prompt, “What does home mean to you?” The responses were overwhelming, thoughtful and touching. Each writer I worked with tells a deeply personal story about their lives and the people they love. Each story touches on connection, even in times apart. Isn’t that what the holidays — and life — is about? But enough from me already. I hope you enjoy these three reader-submitted essays as much as I did.

Hope Carried Across the Mekong

By KatieAnn Nguyen

KatieAnn Nguyen

The night is cold as silent silhouettes make their way across the ripples of the MeKong River. Fear rattles my grandparents’ nerves. They pray that they’ll reach Thailand before the soldiers catch them. The Vietnam War tore their village in Laos apart.

Communism threatened their families.

My grandparents clutch their two young daughters with them. My grandfather was deafened after being taken as a prisoner of war. My grandmother worried about her parents in Thailand. Before they were my grandparents, they were Blia Vang and Xe Vue Thao, two parents hoping for a life without war, without soldiers guarding the roads at night, and without the sound of bullets ricocheting through the air.

Coming to the United States, my grandparents brought with them their dreams — one was to simply be happy. As they began to grow their family, the meaning of together began to take on new meaning.

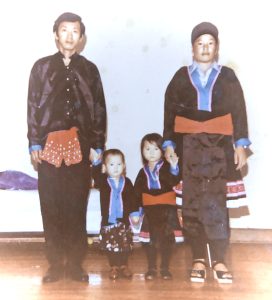

Nguyen’s grandparents escaped Thailand to come to the United States. They are pictured here with their daughters. (Photo: Courtesy of KatieAnn Nguyen)

For my grandparents and their eight children, it meant long car trips to Yosemite, watching Bob Ross paint on their small TV, crushing roaches in their cramped apartment at night. To be together was that feeling of simply being in each other’s company.

When I was born, my parents raised me surrounded with that feeling. I grew up in the smells of my grandparents’ home, herbal medicine and rice cooking in the pot, the noise of small feet on tile floor and cans being crushed for recycling. My grandparents calling me Aang because they couldn’t pronounce my English name.

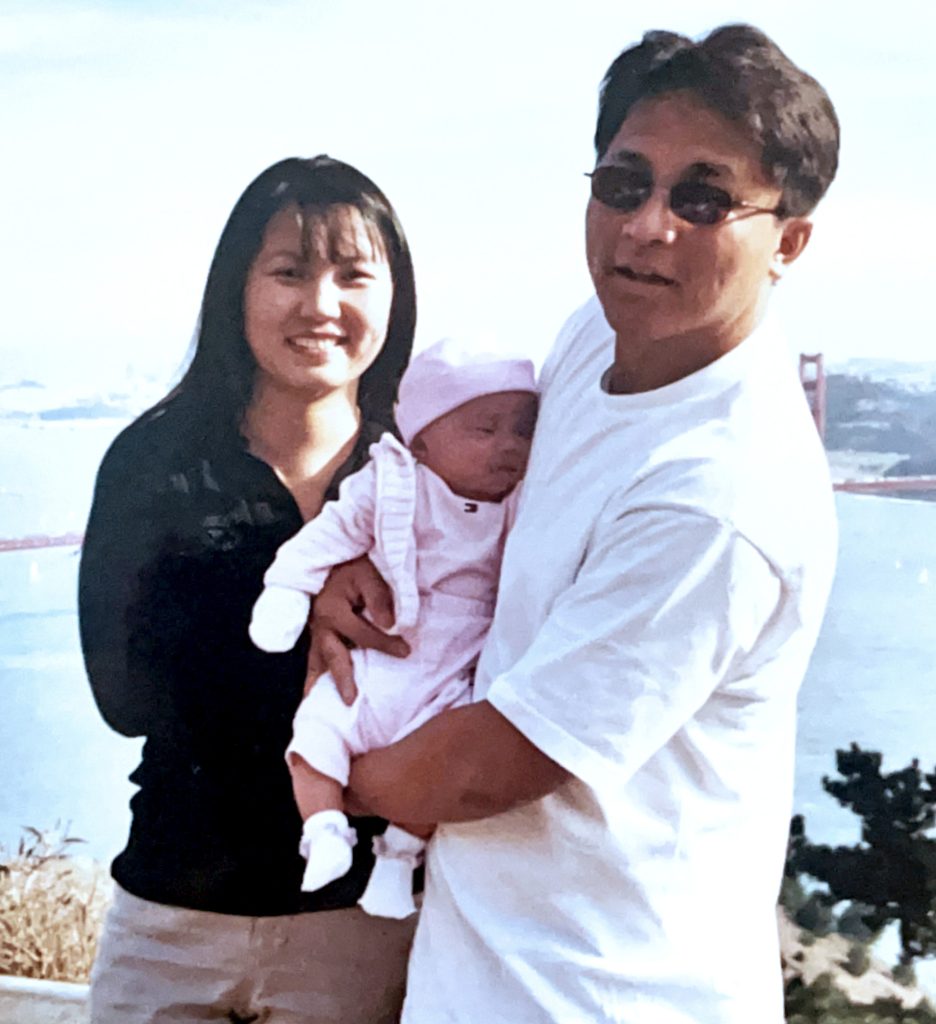

KatieAnn Nguyen, as a baby, in the arms of her parents. (Photo: Courtesy of KatieAnn Nguyen)

Being together meant visits to their house filled with screams of cousins, laughter of uncles and aunts, the smell of boiled chicken cooking on the stove. My grandparents taught me the importance of family, even though I didn’t speak Hmong, and they didn’t speak English.

In that comfort of one another, I learned what it meant to be together. It was more than just an embrace. It was the anticipation of visiting them again the next weekend, the replaying of our memories together and the folklore tales they’d try to tell me in fragments of English.

But when my grandmother passed away in 2016, and then my grandfather in 2021, I found myself wondering what being together meant when they were no longer here. It was during this time of grief that my mother told me the story of when my grandparents came to America.

When they arrived in Thailand, they were lucky enough to enter a refugee camp and be sent to the United States. When she told me this story, I saw reflections of my grandparents’ hopes and dreams. It was more than just a better life in America they were sacrificing everything for, it was a new beginning.

Their story is one of many, a story of immigration for a better life. But to me, it is more than just a story, it is my beginning. Those hardships were passed on to me, those dreams of white-picket-fenced houses, those hopes for a better tomorrow. For them, it was immigrating to the United States, but for me, it was continuing that story, that legacy of our beginning. It was keeping that hope they carried with them across the Mekong River alive.

When I graduated from West County High School in Sebastopol, Calif., last year and began my first year at Dominican University of California, I felt that hope resonating in me. Over these last years without them, I’ve learned what it means to be together even when they’re not here.

It means the beginning they gave their children — and me — their hope for a better life. Every milestone I have reached, I felt as if it was an extension of that hope. For the first time, it felt as if we were together again, connected with that dream of a better future that they began.

KatieAnn Nguyen is a second-generation Hmong-Vietnamese American from California who is a member of the Sonoma County JACL. She is a 17-year-old freshman biology major at Dominican University of California with dreams of becoming a pediatrician.

Together Always Through Food and Traditions

By Joyce Endo

It’s an annual tradition in our family to cook all day on Dec. 31 and past midnight to welcome the new year. We celebrate Oshogatsu, or the Japanese New Year. It is truly a labor of love to cover a table with traditional dishes to share with friends. We make special traditional dishes and display them in platters and containers from Japan. I look forward to this time every year, not just for the special home-cooked meal, but also the bonding time.

June and Joyce Endo (Photo: Courtesy of Joyce Endo)

Joyce Endo is pictured here with her father, Bill Endo, the year he died. (Photo: Courtesy of Joyce Endo)

My parents, Bill and June Endo, became JACL members shortly after we moved to our home in San Francisco, my hometown. As a child, I remember seeing the Pacific Citizen in the mail growing up and reading all the community news.

For the duration of World War II, my mom lived in Japan, while my dad moved to Utah. They did not talk about this time, except about the good memories. When a mutual friend introduced my parents after the war, it was love at first sight!

She and my dad always encouraged me to follow my dreams with piano, violin and ballet. They also encouraged me to connect to my culture. While I was in nursing school, I competed as a Cherry Blossom Queen contestant representing the Nihonmachi Merchants. I’ve always admired the contestants. Never in my wildest dreams did I think I would have the same opportunity. My mom, a seamstress, designed my gown. It was such a joyous experience.

Now for Oshogatsu, I’ve taken over the cooking. I do my best to replicate my mom’s cooking, but it doesn’t taste quite the same. I think the missing link is her loving touch. She smiles ear-to-ear when I make one of her recipes. It warms my heart.

We have always had a close relationship. The pandemic still somehow brought us closer in many ways, especially through cooking and eating!

The author says her experience on the Cherry Blossom court was joyous. (Photo: Courtesy of Joyce Endo)

I spend every day with her. As a Nisei, she is becoming frail, but I like to say she is still strong and mighty. My dad died shy of his 77th birthday, so Oshogatsu looks, feels and tastes different. My dad was always the behind-the-scenes strength and glue. Family is everything to me because of my loving parents.

Even though we aren’t cooking together anymore, the tradition reminds me of our special bond.

Joyce Endo is a Sansei living in Orange County, Calif. She is an Orange County JACL member, who worked as a registered nurse in obstetrics, labor and delivery. She is now a residential real estate agent.

Moments That Take Our Breaths Away

By Kathryn Kimura Mlsna

Being together again gives me the strength to make a difference in the world. My relationships remind me of who I am. They reflect my values, goals and dreams. As a Sansei, my relationships with my ancestors, family and extended family make me proud of my Japanese heritage.

I am researching and writing my family’s historical biographies, so their legacy of courage, strength and perseverance will be passed down. What began as a half-day task to convert my father’s 75-page autobiography, “The Orphaned Generation,” from a typewritten manuscript to a Word document became a full-time, three-year project that grew to include six extensively researched manuscripts with hundreds of pages.

(From left) Kathryn Mlsna, brother Alan Kimura, parents Grace and Eugene Kimura and sister Eugenie Chiu (Photo: Courtesy of Kathryn Kimura Mlsna)

In the spring of 2020, as the pandemic changed our world, I started working on the biographies. They are a gift that reconnects me to my past.

My story began in 1950 when my parents met through a mutual friend at the Chicago JACL.

My mother, Grace Watanabe Kimura, left Poston for Texas to complete her high school and college education in business management. My father, Eugene Tatsuru Kimura, left Camp Harmony/Puyallup to complete his undergraduate and postgraduate pharmacology studies in Nebraska and Illinois, respectively.

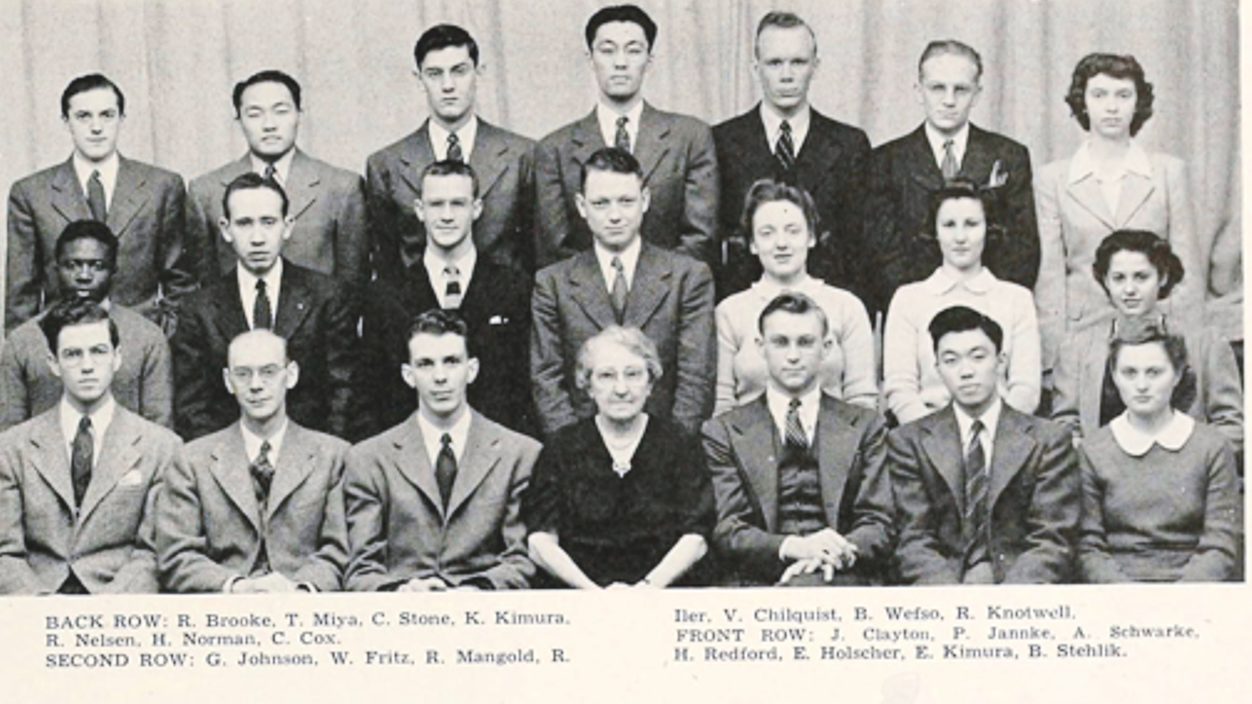

Pharmaceutical Club: Eugene Kimura (front row, second from right) was part of the same club in 1944 at the University of Nebraska with his brother (last row, fourth from left). (Photo: Courtesy of Kathryn Kimura Mlsna)

Paul Yorishige and Chie Watanabe, the author’s maternal grandparents (Photo: Courtesy of Kathryn Kimura Mlsna)

Although my parents spoke about their lives, I didn’t appreciate all the details back then that make their noteworthy lives remarkable. Grace and Eugene overcame the premature losses of their fathers and the loss of civil rights during the war to celebrate academic and professional successes and the joy of raising a family — much in the context of longstanding anti-Asian sentiment that made them feel like perpetual and undesirable foreigners.

During the redress movement, Grace testified at the Chicago CWRIC hearings. Later, my parents gave a thoughtful and well-researched presentation about the incarceration to the residents of their retirement community. Many in the audience were hearing about it for the first time.

Before Grace and Eugene died in 2019 and 2020, at almost 94 and 98 years old, respectively, they lived 15 minutes from me in suburban Chicago. Regrettably, the pandemic prevented us from visiting our father for the last six months of his life.

The biographies, still a work-in-progress, bring me together again with my parents. The manuscripts have also brought me closer to the grandparents I never met – a Baptist pastor and a farmer/hotel proprietor.

It has been said that life is not measured by the number of breaths we take, but by the moments that take our breath away. The value of being together again is not measured by the number of hours we are together, but by our appreciation of the relationships that make us all stronger.

Florida-based Kathryn Kimura Mlsna is a member of the Southeast JACL. She has five beautiful granddaughters and is a wife, mother and grandmother. She spent 30 years working as a lawyer and businessperson for nonprofit organizations and a large restaurant chain. She served as the alumni association’s president at Northwestern University from 2014-16, and she still serves as a volunteer on several boards there.