A new documentary and book examine the impact,

challenges faced by the groundbreaking medical examiner.

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

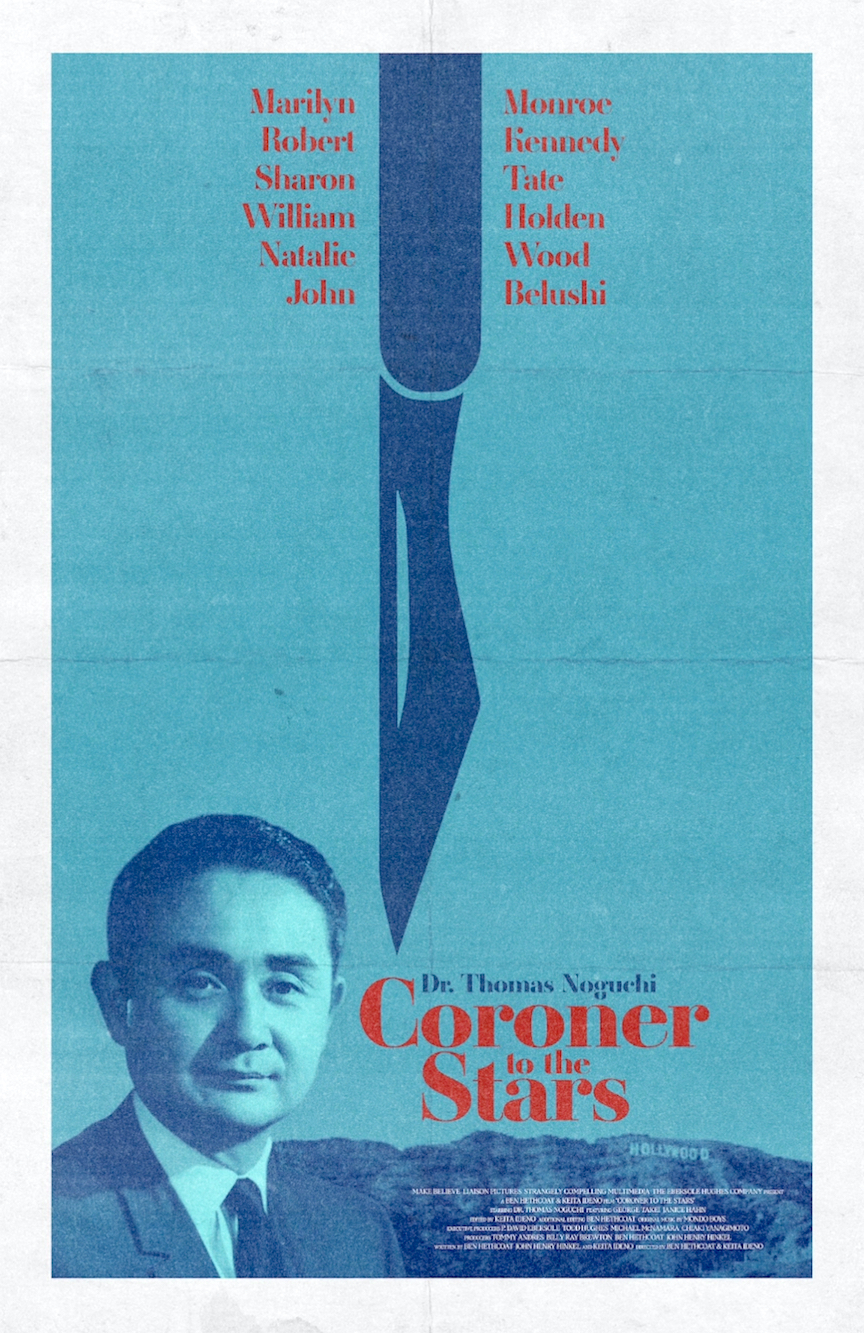

Poster art of “Coroner to the Stars”

At 98, Dr. Thomas Noguchi is back. That’s thanks to a new documentary, “Coroner to the Stars,” co-directed by Ben Hethcoat and Keita Ideno, and a new book, “L.A. Coroner: Thomas Noguchi and Death in Hollywood,” by Dr. Anne Soon Choi (see sidebar story).

A case of synchronicity, two utterly unrelated Noguchi projects arriving at roughly the same time? Perhaps — but it’s safe to say that both the filmmakers and the book’s author wanted to make sure Noguchi’s legacy is secure and that younger generations will appreciate how the Japanese American community rallied to support the Japanese immigrant as he faced institutional obstacles just to keep his job.

For those too young to know his place in history, Noguchi came to the U.S. in 1952 after earning his medical degree in Tokyo in 1951, and he eventually found employment as deputy coroner for Los Angeles County, home to Hollywood and its surfeit of stars.

When Marilyn Monroe — especially then and still now one of Hollywood’s brightest heavenly bodies — died in 1962, it was Noguchi who conducted her autopsy. His conclusion, that she had died of “acute barbiturate poisoning” and was probably a suicide put him on the map to becoming a star of sorts in his own right, which would in the years to come put him in the crosshairs of those who didn’t cotton to him becoming the center of attention.

A young Dr. Thomas Noguchi

Today, when drug-related causes of a celebrity’s death — think ketamine for actor Matthew Perry or propofol for singer Michael Jackson — are shared with news outlets pro forma, the documentary shows how Noguchi’s decades-ago candor about what killed a particular superstar did not endear him to a dead star’s outraged, still-living celebrity pals.

Nevertheless, by 1967, Noguchi rose to become the county’s chief medical examiner. Some of the celebrities whose postmortems he oversaw during his tenure, which lasted until 1982, included blues-rocker Janis Joplin, actors John Belushi, William Holden, Natalie Wood and Sharon Tate, as well as presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy. Even after retiring, he returned to the spotlight during the O.J. Simpson trial in the 1990s, when he served as an expert witness.

The documentary has been making the rounds of film festivals and is making Noguchi a celebrity of sorts yet again. The film features Noguchi himself in interviews, as well as actor George Takei sharing his memories about the coroner to the stars.

For his part, Noguchi is matter-of-fact about his reputation, even at the start of his career, as a notable Asian working on celebrity deaths, and a pioneering role model for those who came after him. (His own fame would spawn TV’s “Quincy, M.E.,” starring Jack Klugman; co-star Robert Ito as Sam Fujiyama was a nod to Noguchi.)

“Looking back, I was the first Japanese pathologist selected to work on a number of high-profile cases . . .” he said by email. “Later, I was appointed head of the L.A. County Coroner’s Office. While I considered it a great honor, I didn’t realize I would be paving the way for future medical examiners, whose field was relatively unknown at the time.”

Although he understood his barrier-breaking role, Noguchi said he didn’t feel pressure during his tenure to be the role model, or to be “more Japanese” or “less Japanese.”

“Although I was born and educated in Japan, when I came to the United States, I was determined to be accepted as an American,” he said. “It was important for me to adapt to the independent spirit and culture of this country.”

Having arrived in the U.S. just seven years after the end of World War II, Noguchi said he didn’t face racism in his work. “In terms of my Japanese background, I didn’t feel I was discriminated against in my day-to-day work as chief medical examiner-coroner of L.A. County,” he said. “My American colleagues were always kind and professional in working with me throughout my career.”

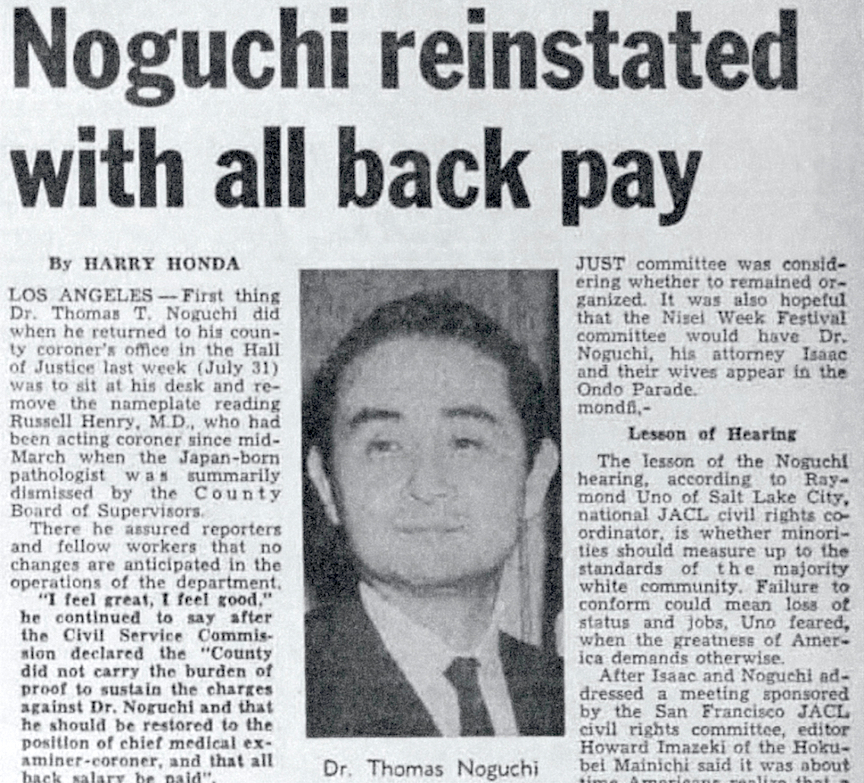

But when his career came under fire for some of his medical pronouncements as well as his penchant for publicity (he was working on dead celebrities, after all), it was the Japanese American community that came to defend him and lobbied for him to keep his position. The Pacific Citizen digital archive contains many articles about Noguchi where Japanese American leaders defended his work.

An article about Dr. Thomas Noguchi by Harry Honda that appeared in the Pacific Citizen on Aug. 8, 1969 (Photo: Pacific Citizen Digital Archives)

“I’m very grateful for the support I received from the Japanese American community throughout my career. Figures like George Takei and organizations such as JUST (Japanese United in Search for Truth) were among those who stood by me,” Noguchi said. “Today, I remain involved with the Japanese community and continue to gather with groups like the Fukuoka Kenjinkai. At 98, it’s a wonderful thing to have community and to celebrate together.”

The two men responsible for the documentary have been honored to work with Noguchi. Hethcoat is the writer, director and producer of the film, and Ideno is a writer, director and editor on the project.

“Growing up, my father was a coroner medical examiner, so I’ve always sort of been involved in some way with the medical examiner community,” Hethcoat said. “And then I had a producer who had found a book that Dr. Noguchi wrote, ‘Coroner,’ on a dollar bookshelf, and he’s like, ‘Huh, this is interesting. I wonder what this guy’s up to these days?’ And, you know, we reached out to Dr. Noguchi to see if he was interested.”

Hethcoat told Noguchi, “We really want to tell your story and for people to see who you are beyond the sensational headlines and beyond just these celebrity cases.”

Hethcoat started working on the project a decade ago, and he asked Ideno to join the team long after it was under way. “Keita came in years after we had already been filming, but he came in at a very pivotal time and in a very important role to help craft a story out of all this material that we had gathered over the years, and yeah, he was an essential collaborator,” he said.

Ideno acknowledged that the fact that he’s Japanese was an asset for the documentary because he felt empathy for Noguchi’s experiences.

“Coming from Japan, just seven years after WWII ended, and what he’s done and his journey is just amazing,” Ideno said. “I came to the U.S. in 1999. I mean, I’m living in a different era, but it’s so hard to be accepted by the American community. So, I just wanted to make sure that his feelings, as a Japanese [were shown], and also Ben and I talked about the deeper theme of this movie is love and support, love from his wife, Hisako, and support from the Japanese American community.”

One thing Noguchi won’t talk about? Which of his cases he is most proud. He becomes downright coy when it comes to the most notable of the deceased stars he examined, though it would be hard to ignore Monroe, whose autopsy put him in the spotlight for the first time.

“Every death is a tragedy for the family, and sometimes for the broader community as well,” he said, diplomatically. “That’s why, in my role as chief medical examiner-coroner, I always tried to be mindful of the family’s needs — especially in cases of sudden or unexpected death. I don’t believe one death is more important than another.

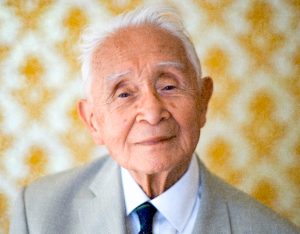

Dr. Thomas Noguchi in the present day (Photo: Ben Hethcoat/‘Coroner to the Stars’)

“For medical examiners, death is something we face every day. And that’s why each case must be treated with dignity and respect.” Wise words from the coroner to the stars.

This article was made possible by the Harry K. Honda Memorial Journalism Fund, which was established by JACL Redress Strategist Grant Ujifusa. To make a donation to this fund, email busmgr@pacificcitizen.org and put Honda Memorial Journalism Fund in the subject line.

Book Resets Noguchi’s

Place in History

Author Anne Soon Choi’s ‘L.A. Coroner’ makes compelling connections.

By George Toshio Johnston, P.C. Senior Editor

Marilyn Monroe. Janis Joplin. John Belushi. Natalie Wood. Robert F. Kennedy. In the Venn diagram of those celebrity names, in the center is another that ties them together in history, news accounts and notoriety.

That name is Thomas Tsunetomi Noguchi, M.D.

As noted (see main story), the former chief medical examiner-coroner of Los Angeles County, aka the “Coroner to the Stars” and inspiration for TV’s “Quincy, M.E.,” which begat the “C.S.I.” franchise, is having a moment, still living and well in Los Angeles, just a couple of years shy of age 100.

On that note, the documentary revisits and reframes a name and career that is likely largely unknown to an audience under, say 50 — and likely semiforgotten but vaguely familiar to those now receiving Social Security benefits.

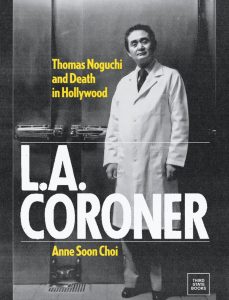

To Dr. Anne Soon Choi, however, Thomas Noguchi was name to a man worthy of re-evaluation that only a well-researched book could provide in terms of being able to dig deeper, provide more context — and elevate him to his rightful station among the pantheon of Americans, of Asian ancestry or not, native-born or immigrant, who have made an outsize impact on this nation’s constantly evolving struggle to make life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness accessible to all.

Cover of Anne Soon Choi’s new book, “L.A. Coroner: Thomas Noguchi and Death in Hollywood”

Photo: Third State Books

That book is “L.A. Coroner: Thomas Noguchi and Death in Hollywood” (Third State Books, ISNB 979-8-89013-005-5, 256 pages, SRP $29.99, Copyright 2025).

According to Choi, assistant vp of Faculty Programs and Initiatives at California State University, Northridge, where she is also a professor at its Asian American Studies Department, the book expands on her award-winning scholarly article titled “The Japanese American Citizens League, Los Angeles Politics and the Thomas Noguchi Case,” which appeared in the summer 2020 edition of “Southern California Quarterly” and is definitely worth seeking.

For Pacific Citizen readers, Noguchi’s story as told by Choi carries particular resonance: The P.C. is among the exhaustive list of sources cited in the article’s footnotes and in the book’s bibliography that helps convey the larger picture of the challenges faced in the late 1960s by Noguchi, then the highest-ranking Los Angeles County employee of Japanese descent.

“I used the run of the Pacific Citizen, particularly starting in about ’65 all the way through the early ’70s where the JACL was heavily, heavily involved in the Noguchi case,” Choi said.

Although more than two decades had passed since the end of World War II, the top of the Los Angeles power structure, city and county, was male and WASP (or WASP adjacent), some of whom found the decidedly non-white Anglo Saxon Protestant Noguchi and his perceived penchant for press coverage off-putting. He also earned the enmity of a bureaucrat in charge of county purse strings by going directly (and successfully) to the powerful L.A. County Board of Supervisors to get more funds for his department.

Choi also relates how some in the L.A. Japanese American community also found Noguchi — a Shin-Issei who could be seen as haughty and self-aggrandizing — to be, in today’s parlance, “not like us.” She also spotlights Hawaii-born Jeffrey Matsui, who at that time served as JACL’s national associate director based in Los Angeles, as a forgotten community leader who had to prod Los Angeles’ mainland-born JAs to wake up to a reality they (and Noguchi himself) seemed reluctant to face, that Noguchi’s termination attempt was blatantly racist and yet one more instance in which fair play and due process had been subverted.

Another person Choi credits in getting Noguchi to fight for his career and, by extension, for Japanese Americans, is Dr. Hisako Nishihara, his Terminal Island-born Japanese American wife who had been incarcerated at Colorado’s Amache concentration camp and understood what was happening to her Japan-born husband in a way he simply could not.

In a nutshell, Noguchi’s trial to be reinstated was not just a cause célèbres that some in L.A.’s Japanese American establishment had to be compelled reluctantly (initially at least) into supporting, it was also a referendum on how much progress or lack thereof had really been made postwar and post-incarceration, whether Japanese Americans in Los Angeles were OK with being seen as the model minority that didn’t rock the boat and accepting of what amounted to second-class citizenship status.

If a biopic about Noguchi ever were made, “L.A. Coroner’s” Chapter Five (“A Wrongful Dismissal”) and Chapter Six (“The Fight for Reinstatement”) could be the central story, set amidst changing times, replete with colorful characters, good guys and bad guys, a journey from hubris to humility, allies in the Black and Mexican American communities, courtroom drama and a timeless story of a David taking on a Goliath.

Choi also posits an interesting theory, that the activism that took place (the formation of JUST or Japanese United in the Search for Truth, a community advocacy group supporting Noguchi that wasn’t officially connected to JACL — but just happened to have several JACLers involved, including Matsui) was a trial run for the redress movement, since many of the same organizing skills were learned and later employed.

Ultimately for Choi, Noguchi’s story is an immigrant’s story, one that is curiously timely. And, though she wrote the book without ever meeting Noguchi (though not for lack of trying), as fate would have it, she actually met him in a way so random that it must have been meant to be, when they both happened to have appointments at the same time at the same eye surgery clinic. In a happy ending that didn’t make the book, they became friends.

Dr. Thomas Noguchi, present day (Photo: Ben Hethcoat / ‘Coroner to the Stars’)

“He’s still very incisive and sharp,” Choi told the Pacific Citizen. “He’s just a lovely person. . . . The people who were so adamantly opposed to him, who were his political enemies, every one of them have all gone.”

Asked what she thought was behind the harmonic convergence-like timing of her book and an unrelated documentary on the same person many may have presumed had already shuffled off this mortal coil decades ago, Choi speculated that it might have been because of the growth of the true-crime genre — think the Manson murders — and conspiracy theories surrounding Monroe, Kennedy and, again, Manson — may have played a part.

“There are a number of things being revisited,” she told the Pacific Citizen. “People are talking about the Manson case again.” Noguchi, she observed, “is very much the footnote to all these famous cases.”

As for what Noguchi himself truly thinks of this renewed interest in his interesting life’s twilight, one can only speculate. He is, as Choi noted, the last man standing among those who sought to remove, silence or degrade him and his career. Maybe the saying, “He who laughs last laughs best” explains his wry, Mona Lisa smile.

EDITOR’S NOTE: A conversation between Dr. Anne Soon Choi and author Naomi Hirahara that was postponed due to the recent unrest in downtown Los Angeles and Little Tokyo has been rescheduled. It is now set for 10 a.m.-Noon on Aug. 9 at the Little Tokyo Branch of the Los Angeles Public Library. To RSVP, send an email to ltokyo@lapl.org or sign up at the reference desk.