A photo from “Rockin’ the Boat” from protest in New York’s Chinatown, circa 1974. (Photo: Mary Uyematsu Gao. Reprinted with permission. © 2020)

New Photojournalism Book Revisits Roots of 1970s Activism

By P.C. Staff

If you love black-and-white photojournalism, then Mary Uyematsu Kao’s new “Rockin’ the Boat: Flashbacks of the 1970s Asian Movement” may be the book for you.

As described on its cover, “Rockin’ the Boat,” which officially launched this month, is a 276-page collection of “Photographs and Narrative” covering 1969–1974, when the consciousness-raising “Asian movement,” as it was then called, sprang to life following the Civil Rights, Anti-War, Environmental and Feminist movements of the 1960s.

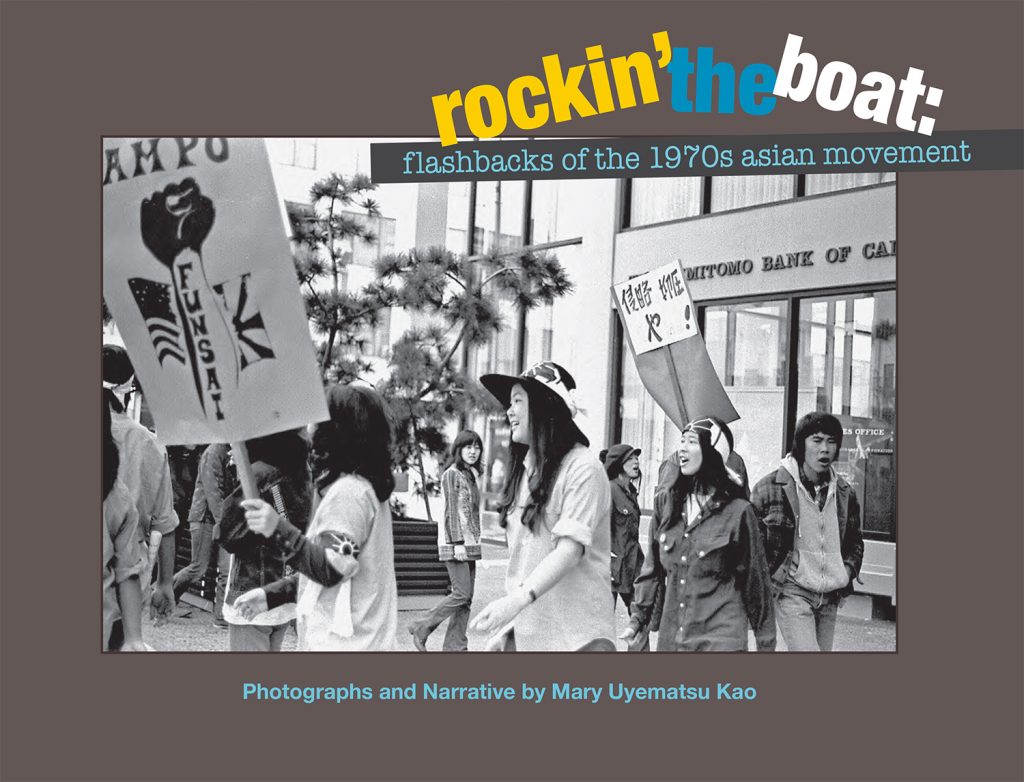

The cover of “Rockin’ the Boat” features a photo of a protest in Little Tokyo in the early 1970s. (Photo: Mary Uyematsu Kao. Reprinted with permission. © 2020)

According to Kao (pronounced “Gao,” with a hard “g”), who retired in 2018 after 30 years at the UCLA Asian American Studies Center, there was no master plan circa 1969 to someday compile her photos into a book.

“I was working on a film at the time. All the photographs that I took were supposed to be for this film, which didn’t get very far,” Kao laughed.

Fortunately, this desire to document the times and Kao’s peers via photography became a gift to younger generations for whom taking a photo is as easy as whipping out a smartphone and sharing via social media.

Back then, though, desire wasn’t enough. One needed a decent camera, film and access to a darkroom. Fortunately for posterity, a young and yet-unmarried Mary Uyematsu had all three: a Mamiya-Sekor 500 TL 35 mm camera, rolls of Kodak Pan-X black-and-white film and the darkroom at Gidra, the L.A.-based unofficial official newspaper of the Asian American empowerment movement.

Mary Uyematsu Kao poses for a self-portrait. (Photo: © Mary Uyematsu Kao. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission.)

Inspired by a UCLA photography class, Kao trained her eye on her friends who were caught up in, according to the book’s introduction, “ … the most exciting, uplifting, and dramatic experience of our young Cold War lives. We were part of the changes that were sweeping the country and the world. It was truly a great time to be alive!”

Despite the beautifully rendered book that resulted, Kao, 70, downplayed her own abilities. “I never got real good technically. A lot of it was just trial-and-error and just the love of doing those things. I messed up so many pictures doing my own darkroom work.”

But the modern digital technology that allows anyone with a smartphone to take a photo also proved beneficial to Kao. “I had this box full of negatives that I had been dragging around,” she said. With a grant in the early aughts from the Institute of American Cultures, she was able to have more than 300 of those negatives, saved in manila envelopes with dates and places written on them, professionally scanned at a high resolution and converted into digital files.

It would take until after her retirement — and yet another grant, plus the cooperation of the Asian American Studies Center to be the co-publisher — for Kao to get going on turning those digitized images into a book. Even with those favorable circumstances, however, it wasn’t easy for her.

“It was really hard getting started. It was like this massive block. It was a writer’s block, because I was approaching it as, ‘I need to write first,’ ” said Kao. “With no progress on that, I realized, ‘This is a photo book. The main reason I’m doing this is because I want to show the photos that I took from that time.’ So then things started moving along.

“I organized everything by chapters with the photographs and then I filled in the writing and that really helped my process quite a lot because then I realized, ‘I don’t have to write that much.’

“You want the writing to complement the photographs, too, so it was important to get those photographs down first, because that was really the inspiration for me. That pretty much solved the problem, and I moved forward from there.”

Mary Uyematsu Kao displays a copy of her newly released book, “Rockin’ the Boat: Flashbacks of the 1970s Asian Movement. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

With her book nearly done, there arose another obstacle: a disagreement between UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center and Kao. “I was asked to change the epilogue and I refused,” she said. “They wanted the stuff about Trump taken out.”

She explained that the Center’s viewpoint was any references to the current resident of the White House stamped today’s political zeitgeist on an otherwise timeless book.

Kao, however, stood her ground and got her way. But, oddly enough, she laughed, “I rarely get my way! Actually, it’s taken me a long time to learn to stand my ground. Being an Asian woman, especially from the era, the Cold War, you’re not taught to stand up for yourself. That’s the last thing they want you to do.”

As for the book’s title, Sandy Maeshiro, a fellow traveler and peer of Kao’s, could relate. “My mother used to say that. ‘Don’t rock the boat.’ It was kind of a Nisei thing,” said Maeshiro. “Whenever I would protest about something, she would say, ‘Don’t rock the boat.’ ”

In other words, don’t disrupt the status quo, don’t bring attention to yourself, keep a low-profile — all variations of the Japanese saying deru kugi wa utareru, or the nail that sticks up gets hammered down.

Coming from Maeshiro’s parent’s generation, that mindset made sense, after the collective experience of being rounded up and incarcerated in American concentration camps during WWII, guilty of the “crime” of having ethnic and cultural ties to a country with which the U.S. was at war, American citizenship notwithstanding.

For the Sansei involved in “the movement,” however, being American as well as Asian meant calling out injustice, racism, unfairness and hypocrisy. Kao’s book, then, is a paean to those idealistic times.

The Sansei were part of America’s Baby Boom generation, which clashed with their parents on anything and everything: politics, music, hair styles, gender roles, patriotism, drugs — and Japanese American boomers and their second-generation parents were not immune to the “generation gap.”

Kao, however, bristles at the memory of how Asian Americans were mistreated by the White members of the Anti-War movement, despite the common goals of ending the Vietnam War. “They had no sensitivity toward Asians or Asian Americans or even the Vietnamese. They couldn’t have cared less.

“The attitude was ‘bring our boys home’ whereas the Asian contingent was telling them, ‘Look what you’re doing to the [Vietnamese] people over there. Do you even consider them people?’

Kao also remembers hearing from Asian American veterans returning from Vietnam. “The guys that came back, they were telling us that they were stood up in [basic] training as ‘This is what a gook looks like,’ and out in the field, not sure if they were going to get shot by either side,” she said.

Members of the Yellow Brotherhood in Los Angeles give a Yellow Power salute, circa 1973. (Photo: © Mary Uyematsu Kao. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission.)

For Vietnam War vet Nick Nagatani, one of his reactions to seeing the book was a bit more lighthearted. “Damn, we were young!,” he exclaimed.

According to Kao, the reaction to the book by those who received early copies were similar, ranging from “nostalgia to people getting energized by seeing and reading – it’s like Facebook, when you go through peoples’ Facebook pages and it’s like, ‘Oh, there’s so and so’ — there’s a lot of that.”

Waxing more seriously, Nagatani, who earned a law degree after his service, became a stalwart member of the L.A.’s Yellow Brotherhood movement and authored the novel “Buddhahead Trilogy,” said of Kao’s book: “It’s historical and it’s academic and if they say a picture is worth a thousand words, then you’ve got millions of words in here, even without the narratives, which add so much life to the pictures.

“When I think about this book, I think about Mary, because she lived it, so when you talk about the ’70s or the ’80s, she has a wealth of information. I remember back in the day, seeing Mary walking around the streets or a demonstration or a wedding or at a pancake breakfast, whatever it might be, with a camera and just like, taking pictures and communicating with people and just being a part of it, but also capturing the moment.”

“We’re still fighting the same fight,” Maeshiro said, “We’re still fighting the racism, the poverty, the oppressive nature of the government, we’re still fighting these wars against people that are just for profit, we’re still fighting a system that’s driven by profit over people. So, a lot of those slogans of those days are just as relevant today.”

“Rockin’ the Boat: Flashbacks of the 1970s Asian Movement”

ISBN 978-0-934052-55-9

SRP: $30

UCLA Asian American Studies Center

3230 Campbell Hall, Box 951546

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1546

Email: aascpress@aasc.ucla.eduor

Write to Mary Uyematsu Kao at:

mugao@ucla.edu

[Kao says if contacted directly, she will sign a copy of the book.]

Kao’s feelings were similar, but she added that she did not see her book “as a call to action.” Rather, she said, “I want people to think about why they are doing what they are doing, like for present-day activists.

“What do they really want? Yeah, you want to end police brutality but what does that entail? It entails a lot more than just fighting police brutality. We’re talking about a whole system here and police brutality is protecting that whole system.”

Picketers at Confucius Plaza in New York’s Chinatown from 1974, protesting the construction contractor’s lack of compliance in hiring construction workers of Chinese ancestry. (Photo: © Mary Uyematsu Kao. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission.)

Although she says she has enough photos to fill two more books, that is not what Kao has in mind to work on next.

“I would really like to clean out my garage and make it a studio space. I really want to paint. That’s kind of where I started out at UCLA as an undergrad is painting,” Kao said.

“It’s just that with painting, I can’t communicate things I can with photography, and photography really fit in at the moment with the movement and as an artist, what could I do to promote what was going on in the movement. So that’s why I ended up doing photography. But inside, there’s this painter. The painter hasn’t emerged,” she laughed.

If her accomplishment with this book is any indication, though, should that painter within Kao ever emerge, whatever is produced will likely rock the boat in its own way.