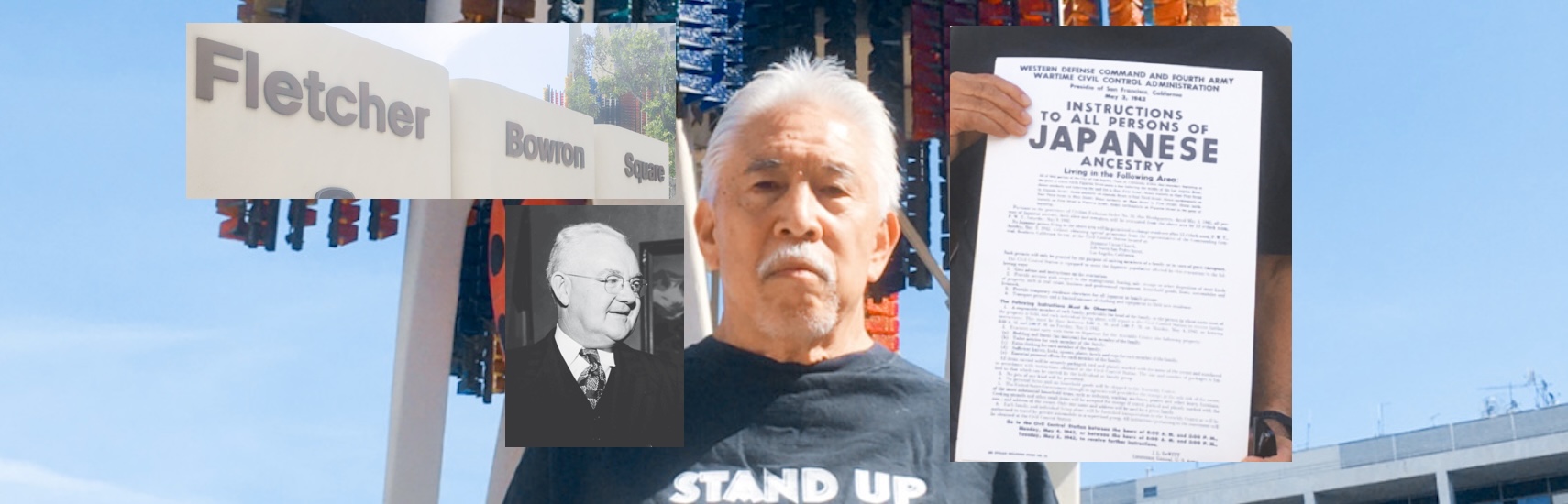

Steven Nagano, center, does not believe the downtown Los Angeles mall pictured to be named to honor Fletcher Bowron (pictured in the inset) because the city’s former mayor was in favor of having ethnic Japanese removed from their homes — and put to work — in remote locations “several hundred miles from the coast” during World War II.

For Steve Nagano, memorial to an L.A. mayor is an affront.

By George Toshio Johnston, P.C. Senior Editor, Digital and Social Media

Within the city and county of Los Angeles are many, many points of interest, sites, buildings, bridges and more named after local politicians, public servants and civic leaders. Kenneth Hahn State Recreational Area. Vincent Thomas Bridge. Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. Julian Dixon Library. Edward R. Roybal Learning Center. Tom Bradley International Terminal. Mark Ridley-Thomas Bridge.

But who among the preceding individuals feted by having a landmark named in their honor said the following?

- “Japanese can never be Americans in the true sense.”

- “We are worried about the problem of divided loyalty on the part of many American-born Japanese.”

- “They are race apart. The accident of birth should not make Japanese born on American soil of parents, who are alien in legal effect and at heart, citizens of the United States.”

- “I advocate the securing of land by the federal government in locations removed at least several hundred miles from the coast … where they may be put to work.”

- “When the war is over, it is hoped that we will not have again a large concentration of the Japanese population in Los Angeles. By that time, some legal methods may be worked out to deprive the native-born Japanese of citizenship.”

Full disclosure: That was a trick question. None among those listed is known to have said anything of the sort. Those words were actually spoken after the United States declared war on Japan, following its attack on Pearl Harbor, by someone whose 1938–53 tenure as mayor of Los Angeles is the second-longest in the city’s history.

Within a short walk of City Hall — and Little Tokyo — is a site that is named for him: Fletcher Bowron Square.

Little Tokyo resident Steve Nagano is leading a campaign to rename it.

Steve Nagano stands atop an outdoor sign marking Fletcher Bowron Square and the Los Angeles Mall in downtown Los Angeles at the intersection W. Temple and Los Angeles streets intersect. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

❖❖❖

Tents of the unhoused line the sidewalk along N. Main Street, toward which a wall announcing Fletcher Bowron Square faces outward. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Fletcher Bowron Square occupies most of one city block in downtown Los Angeles, bordered by W. Aliso and W. Temple streets to the north and south, respectively, and N. Main and Los Angeles streets to the west and east, respectively.

Triforium Sculpture (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Although a bit rundown and in need of a renovation, FBS can actually offer a bit of a respite from the hubbub of DTLA since it doesn’t attract many intentional visitors. Along the Main Street side are the de rigueur tents of America’s ubiquitous urban campers. Its most prominent feature is the colorful Triforium Sculpture.

FBS shares the block with the Los Angeles Mall, which various Yelp reviewers have decried for its lack of cellular service or have savaged with comments like “truly melancholy,” “dark, dismal and desolate” and the “only things missing are a pack of wild dogs and a bear smoking a cigarette.”

❖❖❖

More than 20 years into the new millennium, there have been two trends that arose side by side.

One is the cultural shift that resulted in the reassessment of those aforementioned eponymous sites for some people from yesteryear whose views and actions are now viewed askance by today’s standards.

A metal plaque affixed to the N. Main Street wall of Bowron Square marks the site as the home to the long-defunct Los Angeles Star newspaper.

Perhaps they owned other humans as chattel. Maybe they espoused discredited theories like eugenics or advocated White supremacy or fascism. In some cases, they were military and political leaders who committed treasonous acts.

These reassessments have, in some cases, led to the removal of statues of these figures or the renaming of schools, buildings and other sites upon further reflection and from a 21st-century perspective.

The second trend is people getting tripped and trapped in emails and tweets when their own words are deemed racist, sexist, nationalist, ageist, ableist (all of the “ists”) — or just seen as plumb mad dog mean-spirited. These have led to job loss, cancelation, banishment and shunning.

In the case of the second trend, however, the only thing new is the medium. The penultimate POTUS used Twitter as his bully pulpit to bypass media gatekeepers and communicate directly with his followers.

In Mayor Fletcher Bowron’s era, he did the same thing, but the medium was radio; those quotes of his came from transcribed addresses broadcast on radio station KECA.

Sometimes, the two trend lines intersect. For Fletcher Bowron and his square, this is one of those times.

❖❖❖

According to Steve Nagano, 72, his interest in renaming Fletcher Bowron Square began about three years ago when a friend showed him a decades-old front-page article from the Los Angeles Times that reported Mayor Bowron didn’t want Japanese people returning to the city after the war ended.

“I didn’t think very much of it,” Nagano, a retired public school teacher, told the Pacific Citizen. “But that was a time when African Americans were talking about, you know, renaming things. So, flippantly I said, ‘Yeah, we got to rename that,’ you know. And then I started looking into him.”

Nagano was appalled enough by what he found about Bowron’s words to start an online petition to rename Fletcher Bowron Square; produce a video he put on YouTube that utilized an actor reading excerpts from Bowron’s transcribed radio addresses; and, send a letter to L.A.’s current mayor, Eric Garcetti, that urged him to “begin the process to rename the square, a name that would be representative of the history of the location and the multicultural makeup of the city of Los Angeles.”

Nagano further articulated his reasons for renaming FBS in a 2020 article he wrote for East West ezine: “Our imprisonment during WWII, stems from the same systems that rationalized stealing the land from and committing genocide (ethnic cleansing) against the indigenous people and instituting a system of enslavement, which to many, continues today. It is from the same system that took property from our Issei, shattered dreams of our Nisei, stripped many of their dignity, aspirations and self-respect, and continues to plague our community today.”

❖❖❖

On the topic of history, Nagano told the P.C., “I don’t consider myself a historian, but I love history. And I don’t think we should erase it. And I have the faith in the people that they know enough to discern what is correct or proper.”

Meantime, Abraham Z. Hoffman, 83, who is a historian, shares some traits with Nagano. Both are educators, with Hoffman, who still teaches at Los Angeles Valley College, holding the title of adjunct assistant professor of history. He is also the author of a 2010 article titled “The Conscience of a Public Official: Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron and Japanese Removal,” which appeared in Southern California Quarterly.

Fletcher Bowron (Photo: Toyo Miyatake Studio, gift of the Alan Miyatake Family, used with permission of the Japanese American National Museum)

Like Nagano, Hoffman was born in the L.A. neighborhood of Boyle Heights. On the removal of statues of Confederate “heroes,” he and Nagano are in accord. “I think that in some cases, pulling down statues of Confederate generals is … a good idea — but I don’t want them destroyed. I think they should be put in a museum where their very existence is put into a historical context,” he told the Pacific Citizen.

On whether Fletcher Bowron’s name should be removed from Fletcher Bowron Square, however, he disagrees with Nagano.

By doing that, “you’re erasing all of the good things he did,” asserted Hoffman, who pointed out that “when he was elected in 1938, it was on a reform platform because the previous mayor was corrupt.”

The administration of Bowron’s predecessor, Frank Shaw, is regarded as “being the most corrupt in the city’s history,” according to the 2005 book “Los Angeles Transformed: Fletcher Bowron’s Urban Reform Revival, 1938-1953” by Tom Sitton.

In the book’s introduction, Sitton wrote: “The 1938-1953 mayoral administration of Fletcher Bowron transformed Los Angeles. Not only did the city cope with the tumultuous effects of World War II, it also experienced major changes in its political, social and economic development. The Los Angeles of today is the product of many decisions and actions occurring over many decades. But certain eras — like the Bowron years — marked a particular confluence of these factors that altered patterns and changed the course of the city.”

❖❖❖

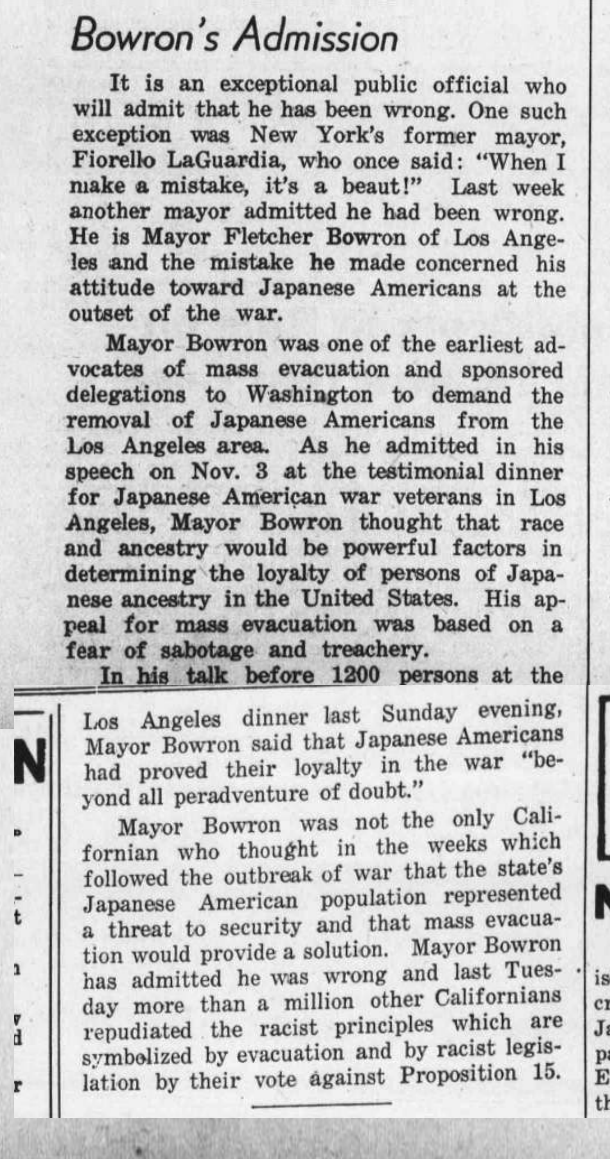

In spite of his alarming rhetoric aimed at ethnic Japanese, on Nov. 3, 1946, Bowron spoke at a testimonial dinner attended by 1,200 people — 500 of whom were Nisei veterans — to, according to a Pacific Citizen article from Nov. 9, 1946, “pay tribute to the wartime record of Americans of Japanese ancestry from Los Angeles.”

Bowron was quoted: “I am glad indeed to make the public declaration that I have been convinced beyond all peradventure of doubt, the Nisei have been true.”

An editorial in the same issue stated: “It is an exceptional public official who will admit that he has been wrong. One such exception was New York’s former mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia, who once said: ‘When I make a mistake, it’s a beaut!’ Last week, another mayor admitted he had been wrong. He is Mayor Fletcher Bowron of Los Angeles and the mistake he made concerned his attitude toward Japanese Americans at the outset of the war.”

❖❖❖

That Fletcher Bowron said what he said is not a matter for debate. Furthermore, his attitudes toward Japanese Americans were not at all outré for the time — they were shared by many, common folk and those in positions of power and influence alike.

Mayor Bowron meets with three Japanese men at Little Tokyo’s Miyako Hotel on March 27, 1950, four years after admitting his error on advocating removing ethnic Japanese from the West Coast. (Photo: Toyo Miyatake Studio, gift of the Alan Miyatake Family, used with permission of the Japanese American National Museum)

“As I noted in the article, he didn’t really understand much about the Japanese Americans. And a lot of what he came to believe was in wartime,” Hoffman said. “There had always been in California, since the early 1900s, a certain amount of prejudice against the Japanese, because they were they were doing too well, they were working very hard, particularly in the agricultural sector. And this aroused a certain amount of resentment.”

In Hoffman’s article, he points out that Bowron depended upon research by an administrative assistant that appear to have served as fodder for Bowron’s radio addresses. From the article:

- Early in January 1942, Bowron requested Alfred Cohn, his sometime administrative assistant and, at the time, a police commissioner, to produce an information memo on the Los Angeles Japanese community.

- Cohn’s confidential memo of January 10, 1942, consisted of an odd distillation of rumors and half-truths. According to Cohn, the Los Angeles Japanese community was “an unassimilable race, forbidden to intermarry with Caucasians, prevented by law from owning real property in the State of California, closely knit to their native land in every conceivable manner.”

- Possibly the most incredible thing about Cohn’s bigoted memo was the degree of seriousness with which Bowron accepted it. The mayor had little or no social contacts with the Los Angeles Japanese or Nisei …

❖❖❖

For Nagano, the question of whether to rename Fletcher Bowron Square has an easy answer: Yes.

But, as Hoffman pointed out, Bowron, “when he realized he was wrong, he owned up to it” — and he apologized. That cannot be said for most of the men in power who, at the time, espoused many of the same opinions spoken by Bowron on the radio but who also were actually in a position to prosecute the eventual incarceration of thousands of ethnic Japanese people, citizen or not, far from their homes, farms and businesses along the West Coast.

And, should Nagano achieve his goal to rename Fletcher Bowron Square, what might that name be? He has a few ideas, but for now, he’s leaning toward a Tongva word — Pokuu’ngare xaa — which his source says means: “We are together, we are as one.”

To view Nagano’s video, visit youtu.be/s_y-T3nCrLA. To sign his petition, visit tinyurl.com/yp9692v3.