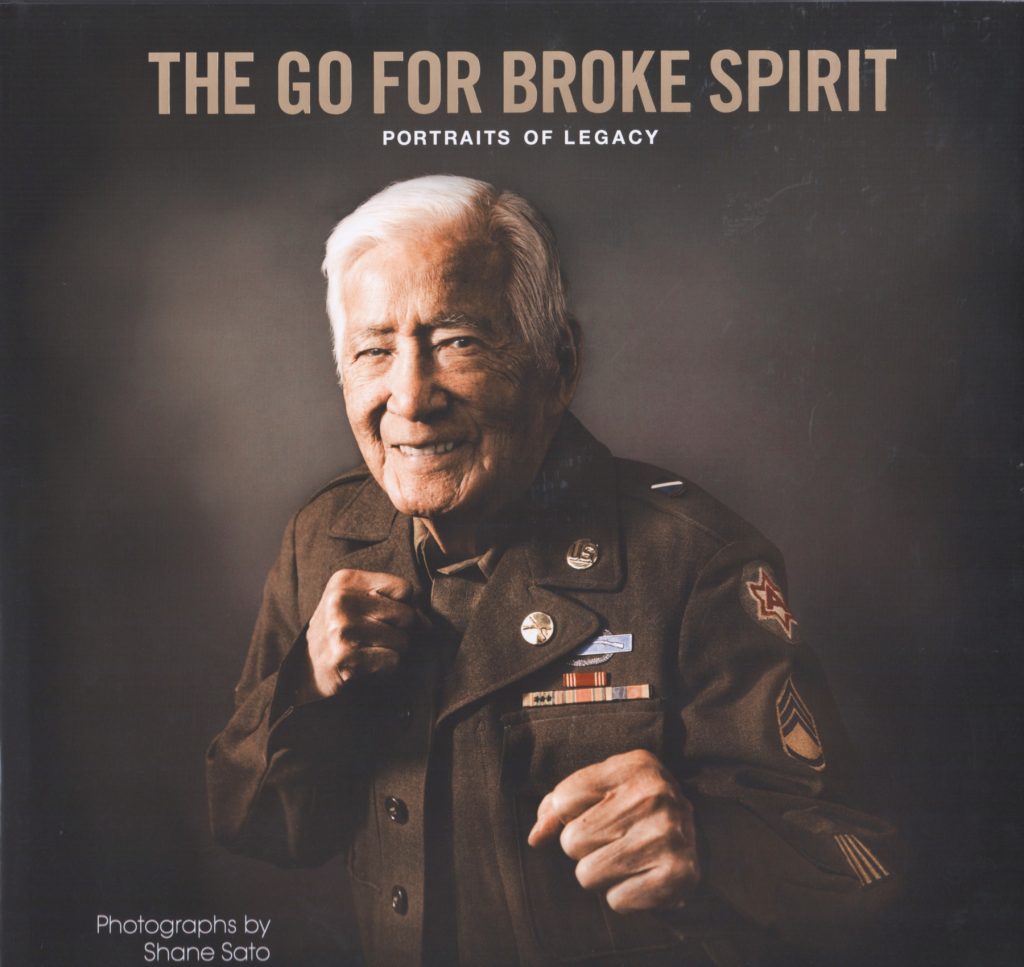

Wat Misaka was among those whose photo appears in Vol. II of “The Go for Broke Spirit” containing portraits by Shane Sato.

A sister tome contains more vet portraits for the ages.

By P.C. Staff

Since publishing “The Go for Broke Spirit: Portraits of Courage” two years ago (Pacific Citizen, Nov. 3, 2017), photographer Shane Sato has been busy — and not just promoting that photographic collection of portraits of Japanese American World War II veterans and others who embodied the “go for broke” ethos they exemplified.

In addition to his marriage to Claire Hur, Sato has been busy promoting that first book but also finishing the second, a sister book titled, “The Go for Broke Spirit: Portraits of Legacy,” copies of which just arrived from the printer and includes unseen photos as well as more recent portraits.

Sato, who describes himself as a half-kotonk, half-buddhahead Sansei, said the response to Volume One was “very positive.” In that collection, each portrait was accompanied on the facing page with text that encapsulated the subject’s story. “Everyone likes the photos, and they all think the stories are very good,” Sato said.

“The Go for Broke Spirit: Portraits of Legacy” shares the same mission as its predecessor, said Sato, and that it’s not just about the veterans or to discuss history. “It’s to get the next generation involved and open up the conversation, which my family and I never did,” he said.

“The only thing my family ever talked about was go to school, get a job, be successful, become a doctor or lawyer, which obviously never happened,” Sato said.

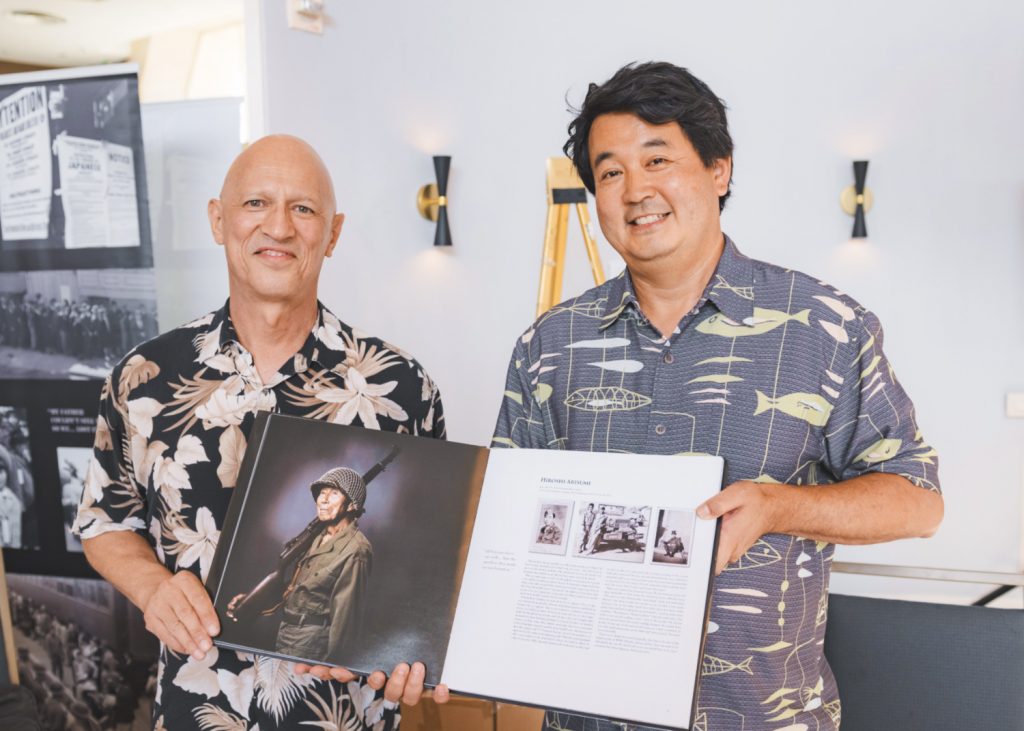

Robert Horsting, left, and Shane Sato display Vol. I of “The Go for Broke Spirit” at the recent San Diego JACL gala. (Photo: JadeCoastPhoto.com)

Sato never really got much from his family in the way of their experiences as Americans of Japanese ancestry, which for his Hawaii-born father included owning and operating Sam Sato Bowling Supply and for his mother, the former Mary Yasuda, working for the city. They met at the long-defunct but fondly remembered Holiday Bowl in L.A.’s Crenshaw District.

“Everyone who bowled in Los Angeles at that time knew my dad,” Sato said, adding, “The only thing my dad told me about his childhood was, ‘Don’t do what I did. Do something else.’”

Later in life, Sato realized his mother was equally reticent about her past, which included living at the Poston 3 WRA Center. Not even direct questions elicited much of a response.

“My mom never talked about camp,” he said. “They never talked about injustice. I had no idea what redress was.”

Asked to speculate why, Sato said he’ll never know why his folks never opened up about the past. But while producing his books, he noticed the same was true with other Japanese American families.

“Talking with a lot of these veterans and veterans’ families, it’s the same story,” he said. “It could have been a shameful time for them. They didn’t want to go back to that time when they were forced to go to camp.”

For Sato’s parent’s generation, he believes the intention behind not talking about that past may have been to give their offspring “a clean slate” and not grow up with a chip on their shoulders.

Still, it left a void that Sato was compelled to fill — and producing this second volume of portraits was like a soothing balm for him.

“My parents would tell me, ‘It’s not important’ all the time. Don’t worry about our past, and so I believed them,” Sato said. “But in reality, their past was very important, and I didn’t realize until much later in life that they were wrong. So now, I try and tell those stories because many, many Sanseis don’t know about their family history, nor do they know about the war necessarily. They know about internment, but they don’t know necessarily what their families had to go through because, again, their families didn’t talk about it.”

Like with the first book, which Robert Horsting helped promote and produce, he again collaborated with Sato for Vol. II to write the aforementioned profiles that accompany each portrait. [Note: Both books are available at thegoforbrokespirit.com/store]

“Just like before, we took different ones if we had a personal relationship or some kind of angle to a particular story, depending on who the veteran was,” he said.

Over the past two years since the first volume was released, Sato traveled to Chicago, Colorado, New York, Utah and Washington, D.C., to collect more portraits for inclusion in his latest offering.

One unexpected development Sato had to deal with was the tariffs imposed by President Donald Trump upon China, where the book was printed. Because of that, Sato said the price has not yet been settled. “It’ll be at least $55,” he said.

The trade tensions may also have even caused the book to be red-flagged this time around by Chinese authorities, who thought it might be some sort of pro-Trump book.

“My broker had to explain to them that they (the veterans in the book) fought for America, but they also fought against the government for the injustice that happened to them,” Sato said. “They could not understand that. They just did not get it. But we were able to get the book through . . . I found that kind of funny.”

“The Go for Broke Spirit: Portaits of Legacy” continues the mission of its predecessor, to get the next generation involved and open up the conversation.

Through Nov. 24, Sato’s portraits will be on display at the JACCC’s George J. Doizaki Gallery in Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo. Included will be some newer portraits not in either book, with veterans from the Korean and Vietnam Wars, as well as America’s long-running conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan.

While it has been a personal and financial sacrifice for Sato to make the books, one difference in the producing the second book that Sato noticed was less reluctance by the veterans compared with 15 years or more years ago.

“Getting them to do the photo shoot and open up was much, much easier,” he said.

To that point, Sato had a humorous story about a vet in Hawaii who was looking through the first book. He looked and looked for a portrait of himself — but didn’t see one.

“How come I’m not in this book?” he asked. Someone had to tell him that Sato asked him three times if he would pose for a portrait, to no avail. Chagrined, the vet said, “I didn’t know it was gonna be good!”