The traditional “roll call of the camps” to recognize each of the

10 War Relocation Authority incarceration centers that forcibly housed

more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent during

World War II. (Photo: Courtesy of Matthew Weisbly)

Following a three-year hiatus, nearly 1,000 unite to remember and honor legacies, support communities and strengthen and provide hope for the future.

By Charles James, Contributor

After a three-year hiatus — the result of Covid-19 pandemic restrictions on large public gatherings — the Annual Manzanar Pilgrimage, which first began in 1969, was able to be held face-to-face again on April 29 to the delight of approximately 1,000, largely unmasked, celebrants.

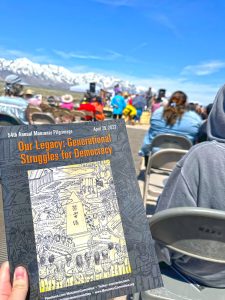

A close-up photo of this year’s Manzanar Pilgrimage program (Photo: Courtesy of Matthew Weisbly)

While the number of participants appeared down from previous in-person pilgrimages, something not entirely unexpected coming out of the pandemic, the upshot was that one could clearly see the smiles on people’s faces, simply happy to be able to see and enjoy being with and around each other again. This 54th Annual Pilgrimage also marked the 50th anniversary of the dedication of Manzanar as a state landmark in 1972.

This year’s program theme was “Our Legacy: Generational Struggles for Democracy.”

Even the weather at the Manzanar National Historic Site, located in Independence, Calif., seemed to be cooperating, providing this year’s pilgrimage attendees with sunny, almost cloudless skies, mild temperatures in the low 80s with a slight breeze against the backdrop of the snowcapped peaks of the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Those who have attended pilgrimages in the past will recall that the weather has not always been this generous to participants. Some years have seen bitterly cold and very windy days. This day, however, was perfect. And plenty of water was provided in cups for anyone that needed it.

After opening with a performance by UCLA’s Kyodo Taiko in this, the group’s 17th appearance at the pilgrimage, participants were welcomed to the MNHS by Superintendent Brenda Ling, followed by tributes to the memory of Jim Matsuoka, one of the original founders of the pilgrimage in 1969 and a longtime, valued member of the Manzanar Committee, and the late-Rev. Alfred Tsuyuki, who led the Konko Church of Los Angeles for nearly 40 years and presided over purification ceremonies at the well-known Manzanar Ireito monument in the site’s cemetery, best-known as the “Soul Consoling Tower,” which was built in 1943 to memorialize the deceased.

Members of UCLA’s Kyodo Taiko (Photo: Charles James)

Also mentioned was the recent passing of Wilbur Sato, a former Manzanar incarceree, who was also a longtime member of the Manzanar Committee, a winner of the 2018 Sue Kunitomi Embrey Legacy Award and a noted community activist.

Nikkei Student Union alumni and members from California State University, Fullerton; California State University, Long Beach; and Cal Poly Pomona (Photo: Charles James)

Every year is becoming a reminder of how few of the remaining camp incarcerees are still alive and how important it is to celebrate their lives and honor their memory.

Bruce Embrey, son of the late Sue Kunitomi Embrey and the current chair of the Manzanar Committee, spoke about how important it was to see the in-person return of the pilgrimage after a long three-year absence. He noted that “much has happened since 2019” … and that “we need to be here to stand with other communities, whether it is Black legislators expelled in Tennessee or a trans legislator expelled in Montana.”

Manzanar Pilgrimage keynote speaker Manjusha P. Kulkarni, executive director of the AAPI Equity Alliance (Photo: Matthew Weisbly)

Keynote speaker Manjusha P. Kulkarni, the executive director of the Asian American and Pacific Islander Equity Alliance, spoke bluntly and realistically about the need for Asian Americans — and all those of color/race — to stay vigilant against racism that has plagued America from its beginnings to even today, citing “The Naturalization Act of 1790 that allowed only ‘free white persons’ to naturalize to become U.S. citizens.”

She added, “ … in the 1920s, California and other states passed Alien Land Laws” to prohibit nonwhite immigrants (especially Asians) from owning property, saying “These laws literally stole millions from their rightful owners.”

Kulkarni also warned of the dangers of “misogyny and imperialism” that are putting Asian Americans today in harm’s way, leading to verbal harassment, physical assaults and discrimination,” noting that “a recent University of Chicago study found that almost 50 percent of our community members — 10 (million)-12 million individuals across our nation — reported experiencing anti-Asian hate in the past few years.” It was a very good speech and both a warning and a reflection of the times we are still witnessing and living in even today.

There were two other keynote speakers on the program. The second speaker was renowned oral historian, professor, author and Manzanar expert Art Hansen, emeritus professor of history at California State University, Fullerton.

Historian and keynote speaker Arthur Hansen with Monica Embrey (Photo: Charles James)

Hansen noted that he was very recently diagnosed with an advanced cancer that will likely greatly shorten his life, and this weekend at Manzanar might well be his last attendance at the pilgrimage. But rather than be negative about his personal health, he sounded a hopeful note on his treatment, choosing to speak about his latest book, “Manzanar Mosaic.”

The book is described as “providing a new mosaic-style view of Manzanar’s complex history through unedited interviews and published scholarship on politics and social formation of the Japanese American community before, during and after World War II.”

Hansen’s speech was followed with another performance by UCLA Kyodo Taiko and then a few remarks by Dreisen Heath, a researcher and advocate with the Why We Can’t Wait Coalition. Heath emphasized the importance that the pilgrimage serves to inspire activism by others fighting against discrimination for acknowledgement of their human and civil rights.

Speaker Dreisen Heath of the Why We Can’t Wait Coalition (Photo: Charles James)

“Feeling the sacredness of a place helps you to press ‘pause’ and be reminded why you are in this and helps to ignite or reignite one’s commitment to activism,” Heath said. “Our fights are interconnected, and we can’t run away from that reality.”

The procession of incarceration center banners (Photo: Charles James)

The pilgrimage’s formal program ended with the traditional interfaith service at the Ireito monument in the cemetery. The meaning of the Japanese Kanji characters on its side read “Soul Consoling Tower,” and it was built in 1943 by master stonemason Ryozo Kado, along with the help of Block 9 residents and a young Buddhist’s group, and designed by Buddhist minister Shinjo Nagatomi to pay tribute to Manzanar’s dead.

In addition to UCLA Kyodo Taiko, musical entertainment was also provided by artist and musician Will Loya of Los Angeles and Los Manzaneros, a group of musicians connected by more than 40 years of camaraderie and political activism. Many in the group have been involved for several years in the pilgrimage, and they performed a well-received song titled “Here at Manzanar,” composed by Mundo Armijo with lyrics by Juan Taboada and Los Manzaneros.

Musical entertainment, spiritual and inspirational words and a reminder that history matters were all on display at this year’s 54th Annual Manzanar Pilgrimage.

Why Manzanar Is Important to Us All

By Matthew Weisbly, JACL Education and Communications Coordinator

Matthew Weisbly

My family was not incarcerated at Manzanar, though they should have been. When the calls for voluntary “evacuation” came in early March 1942, my family was some of the few who listened. They sold their farm, packed up their belongings and piled into my great-grandfather’s truck, heading east.

Originally from Morgan Hill, Calif., they ended up staying near Turlock for a few days to try and sort out where they might go next. While they were there, the second set of exclusion orders came out, and they learned they could no longer leave California. As a result, my family was incarcerated instead at Gila River, Ariz. They decided to remain in Arizona after the war ended, some of only 500 Japanese Americans who did so from Gila River.

So, I have no personal connection to Manzanar, yet I wanted so badly to attend the Manzanar Pilgrimage one day. I was lucky enough to attend my first in 2019, the 50th anniversary of the pilgrimage and the last before the pandemic. It was a moving and beautiful experience, and I decided then that I’d go to as many as I could.

So, I have no personal connection to Manzanar, yet I wanted so badly to attend the Manzanar Pilgrimage one day. I was lucky enough to attend my first in 2019, the 50th anniversary of the pilgrimage and the last before the pandemic. It was a moving and beautiful experience, and I decided then that I’d go to as many as I could.

But we all know what kept us from attending more in 2020, 2021 and 2022. So, as the pilgrimage returned in 2023 for the first time since then, I knew I wanted to go. I went with my friends, one who like me had family at Gila River as well as Tule Lake, and another who is South Asian and has no family connection to the incarceration story. But we all made this trek for a reason.

We talked about it on the car ride up and back from Orange County, nearly five hours to get there on Friday afternoon and roughly four hours coming back on Saturday night — plenty of time for random conversations, spontaneous karaoke sessions and a debrief of our time together.

We talked about why this was important to us despite not having a connection to Manzanar and how for those of us who are Japanese American, this pilgrimage and Manzanar itself represent all that happened to our family and our community.

It’s a way for those of us who may not be able to pilgrimage back to our family’s camps, or who don’t know where their family may have been, to still honor and respect those legacies. It is also something that I think many Japanese Americans share in common — we have a goal of someday making a pilgrimage to all 10 camps, so as to truly honor all 125,000 who suffered through the war.

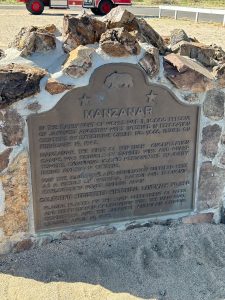

But Manzanar also represents something outside of our community. It represents a dark time in our nation’s history when our laws, our government and the people meant to protect us didn’t. It’s a stark reminder of how fragile our democracy and our very way of life can be.

It’s also something all too similar for other marginalized communities who have experienced the same mistrust, hatred, racism and representative failure firsthand. It is why we are joined by members of the Paiute and Shoshone tribes, whose land Manzanar resides on and who were forcibly removed from it. It is why we are joined by Muslim and Arab American groups who felt the fear of mass incarceration and xenophobia following the 9/11 attacks and the subsequent war on terror. It is why Black organizations join us as we call for HR40 and the need for Black reparations, just as they joined us in calling for redress and reparations in the 1970s and ’80s. It is why one of the keynote speakers, Manjusha Kulkarni, who is Indian American, spoke about the need for solidarity and coming together as communities to support one another, especially in the midst of widespread anti-Asian hate, violence and especially scapegoating. That is why my friend, who has no connection to Manzanar, wanted to join us.

That is why we make these pilgrimages each year, whether our families were incarcerated there or whether they were even incarcerated at all. They stand as a symbol of solidarity, hope, change and remembrance for our community and all communities to ensure that when we say, never again, we truly mean it.

Matthew Weisbly is the JACL education and communications coordinator. He is based in the organization’s Los Angeles office.

A Buddhist priest awaits the start of the Interfaith Ceremony at Manzanar, which took place at the Ireito Monument. (Photo: Scott Lew)