“Under the wave off Kanagawa (‘The Great Wave’)” from “Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji,” late 1831. Color woodblock print. Japan. 2008,3008.1.JA (Photo: Trustees of the British Museum. Acquired with the assistance of art fund and a contribution from the Brooke Sewell bequest)

Katsushika Hokusai, best known for his masterpiece ‘The Great Wave,’ has an enduring influence across the arts.

By Alissa Hiraga, Contributor

Nearly two centuries ago, Katsushika Hokusai imagined a magnificent scene off the shores of Japan — a frothy, giant wave menacing fishermen on their boats. Snow-capped Mount Fuji is perceptible in the distance, its serene, fixed form a contrast to the ferocious movement of the sea.

“The Great Wave (Under the Wave Off Kanagawa)” continues to permeate our imagination and psyche as a singular example of Japanese woodblock prints. It’s certainly the most recognizable image in Hokusai’s “Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji” series.

Viewers who become familiar with the series discover the works are a visual homage to the sacred Mount Fuji, which held a deep spiritual significance for the artist. It began as a set of 36 images and expanded to 46 due to commercial success.

“Snowy morning, Koishikawa” from “Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji,” about 1832. Color woodblock print. Japan. 1927,0613,0.13 (Photo: Trustees of the British Museum, given by RN. Shaw)

The portraits illuminate what daily life was like in Edo, Japan. “Snowy morning, Koishikawa” is set against a tranquil snow-covered landscape where a group enjoys the view and birds flying overhead. In “Fuji View moor, Owari province,” the image conveys the unsung glory of a day’s hard work. The vibrant Prussian blue pigment used in “The Great Wave” is prominent throughout series.

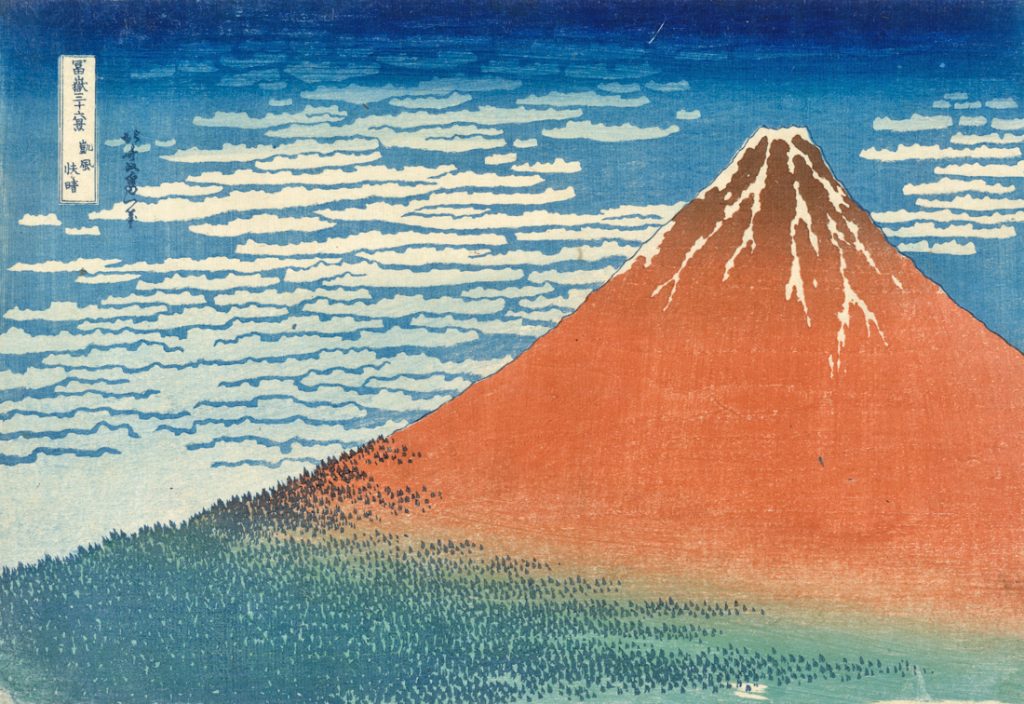

“Clear day with a southern breeze (‘Red Fuji’)” from “Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji,” late 1831. Color woodblock print. Japan. 1906,1220,0.525 (Photo: Trustees of the British Museum)

Hokusai uses a wide range of color effects as seen in the stunning “Red Fuji” portraits, with hues that evoke the stoic nature of the mountain: a peaceful view in “Clear day with southern breeze” and during a storm in “Sudden rain beneath the summit,” where lightning appears to scar the base of the mountain.

“Thirty-six Views” reflects Hokusai’s interest in the eternal — Mount Fuji is the constant, while the elements and sceneries around it are in flux. Hokusai was enthralled with the notions of progress and transcendence, believing his talent would grow with age to reach a divine artistry in his 100s.

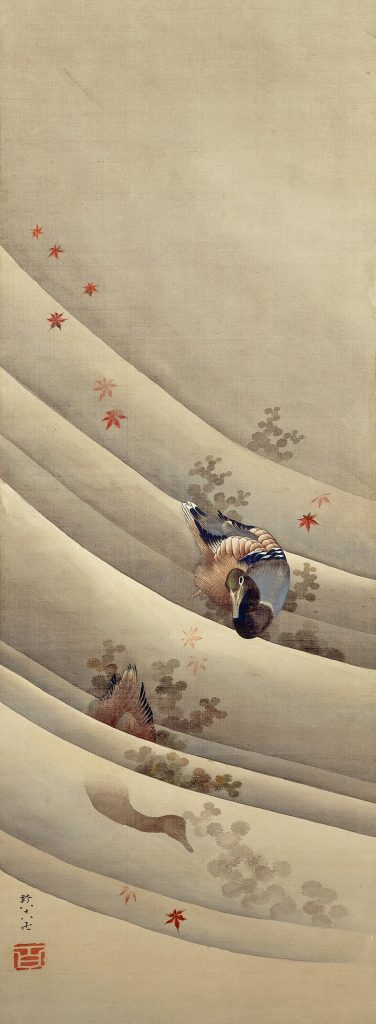

Hokusai’s skill never diminished with age — “Thirty-six Views” was created in his 70s, and the superlative “Ducks in flowing water” was produced a few years before his death at 89.

“Ducks in flowing water,” 1847. Hanging scroll painting, ink and color on silk. Japan. 1913,0501,0.320. (Photo: Trustees of the British Museum. given by Sir W Gwynne-Evans, bt.)

He used different names throughout his artistic career (Hokusai in translation is “North Studio”), with each name representing a life milestone or spiritual belief. While impressively productive in old age, Hokusai produced remarkable works during his early years. Among these are exquisite hanging scrolls of flowering plum trees, birds and “Warrior hero Tametomo and the inhabitants of Onigashima Island,” intricately layered with colors and cut gold leaf.

“Warrior hero Tametomo and the inhabitants of Onigashima Island,” 1811. Hanging scroll painting, ink, color, gold and gold leaf on silk. Japan. 1881,1210,0.1747 (Photo: Trustees of the British Museum)

Born in 1760, Hokusai created his art during the Edo (Tokugawa) period, when Japan was shut away from the rest of the world. In 1638, violent persecution of Japanese Christians and the perceived threat of Western influence drove the shogunate to close Japan off from the world in a heavy-handed lockdown that would last more than 200 years.

Japan’s culture and economy flourished during this isolation, as the country reimagined itself as a physical and spiritual bubble or “floating world,” apart from the travails of human existence. Entertainment districts and indulgent pursuits thrived.

“Ukiyo-e” art or “pictures of the floating world” was born out of Edo (now Tokyo). Paintings and woodblock prints depicted beauty, Kabuki theater and nature. With origins as a woodcutter’s apprentice and working at a studio that specialized in Kabuki prints, Hokusai would create an estimated 30,000 prints over a 70-year artistic period.

He touched across the visual and performing arts through his paintings and wood block prints, as well as through his interpretations of literature and poetry, such as the design series of the classical “One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets.”

He traversed mediums and subject matter, working with brush paintings and paper art. Hokusai is known to be the first to use the term manga with a collection of drawings for his students called “Hokusai Manga.”

“Cormorant and morning glory,” about 1830-32. Hanging scroll painting, ink and color on silk. Japan. 1881,1210,0.1899 (Photo: Trustees of the British Museum)

“Beyond the Great Wave: Works by Hokusai From the British Museum” is currently showing at the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, Calif. The traveling exhibition features more than 100 paintings, drawings, woodblock prints and illustrated books preserved by the British Museum. The exhibition also shares the stories of six collectors who helped the British Museum build the Hokusai collection in the 1850s.

For Alfred Haft, curator of the “Beyond the Great Wave: Works by Hokusai From the British Museum” exhibition, Hokusai and his works embody wonder and possibilities.

“Hokusai was fascinated by everything around him and used his astonishing skill to bring the world to life through his incredibly detailed and varied paintings, prints and book illustrations. He puts us in touch with people, places and circumstances that, at first, might appear strange or new, but he makes them feel believable and real. He welcomed an encyclopedic range of subjects into his art, and that diversity has attracted a wide range of admirers. His art is amazing, but so, too, is his life story. Hokusai faced one personal difficulty after another; yet, he continued to improve and perfect his art through his very last years,” Haft told the Pacific Citizen.

Hokusai died in 1849, several years before Japan reopened to foreign trade and art works began to circulate across seas. Although the artist never traveled outside of Japan, his works influenced new directions in Western art.

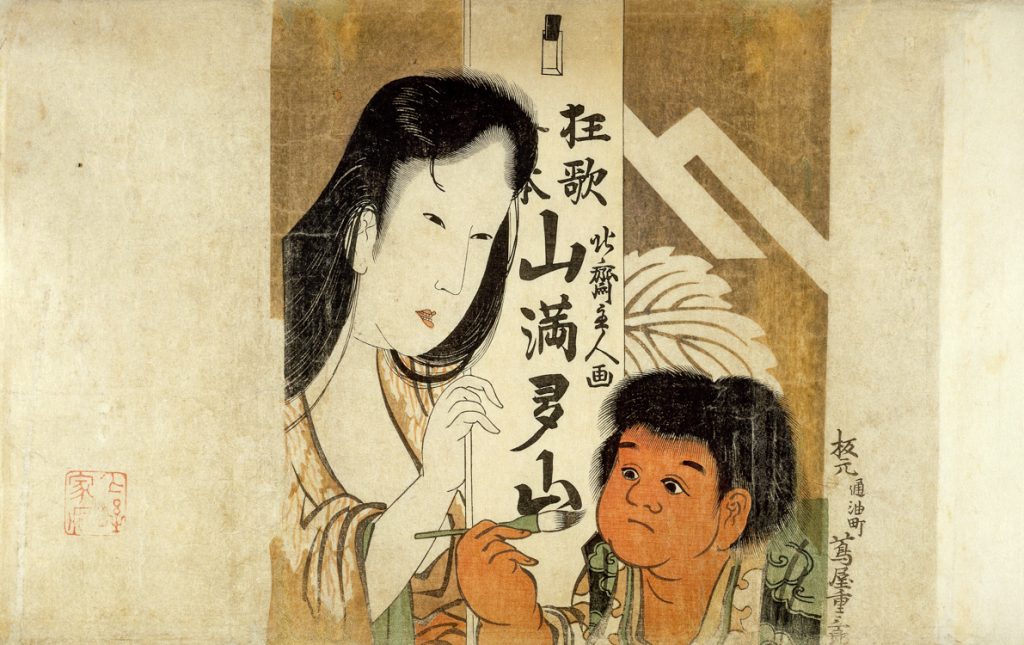

Printed wrapper for “Mountains upon mountains,” 1804. Color woodblock print. Japan. 1979,0305.0.440.4 (Photo: Trustees of the British Museum. given by Sir W Gwynne-Evans, bt.)

Hokusai’s woodblock prints and paintings inspired American and French Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Vincent Van Gogh, J. Alden Weir and composer Claude Debussy. Hokusai’s works remain in the creative consciousness across the arts.

For writers, Hokusai’s sublime works hold profound meaning in the exploration of concepts like change, interconnectedness and transcendence. Naomi Hirahara’s historical mystery “Clark and Division” was the Bowers Museum’s October Book Club selection and paired with the “Beyond the Great Wave” exhibition.

The Edgar Award-winning author is one of the most important writers today for smart, satisfying mystery novels and her works on the experiences and contributions of Japanese Americans.

“I am currently drafting my next Japantown Mystery, ‘Crown City,’ in a journal featuring Hokusai’s iconic wave print. Even though it’s a two-dimensional image, Hokusai is able to capture the power and movement of that wave, which, for me, is symbolic of change, not only in the world or society involving things Japanese but also the plot lines in my mysteries. I take a very Western genre — the mystery — but populate it with Japanese American-centric characters, which inevitably alters the form. There’s a clash of aesthetics and archetype characters. For instance, instead of the lone detective we see in noir standards like Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, we have a young Japanese American woman, Aki Ito, who is very much connected to her family and community as both a choice and necessity as she’s dealing with the aftereffects of the World War II camp experience,” said Hirahara.

In Naoko Abe’s delightful, award-winning book “The Sakura Obsession: The Incredible Story of the Plant Hunter Who Saved Japan’s Cherry Blossoms,” the subject is British adventurer Collingwood Ingram and his efforts to save the endangered great white cherry or Taihaku.

The book is a superb historical study of Japan and its cherry blossom varieties. At its heart is a poignant portrait of Ingram and his contributions in preservation. Hokusai and Ingram coincidentally shared the same birthday, 120 years apart, and, more significantly, a spiritual connection with nature.

“Poet Kan Ke (Sugawara no Michizane)” from “One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, Explained by the Nurse,” about 1835-1836. Color woodblock print. Japan. 1919,0715,0.4 (Photo: Trustees of the British Museum. given by Sir W Gwynne-Evans, bt.)

In “The Sakura Obsession,” Abe writes, “Hokusai, a member of Buddhism’s Nichiren sect, believed that Japan’s tallest mountain possessed secrets of immortality. Mount Fuji and cherry blossoms appeared in his most famous woodblock prints, which were usually carved on cherry wood from the mountains.”

Ingram, who named his own tree varieties after Hokusai, felt a kinship with the artist.

Abe shared with the Pacific Citizen, “Collingwood Ingram learned about Hokusai when Japonisme, the 19th-century love for Japanese arts and crafts in Europe, reached England. Ingram shared his fascination of Mount Fuji with Hokusai. Hokusai expressed the wonder and mysteriousness of nature by painting Mount Fuji from many different angles to show its almost supernatural and transcendental beauty. For Ingram, who did not believe in a Christian god, nature was his religion and faith. I think that kind of awe toward nature’s ‘supernatural beauty’ is what Ingram saw in Hokusai’s paintings.”

“Beyond the Great Wave: Works by Hokusai From the British Museum” is on view at the Bowers Museum until Jan. 7. For more information on the Bowers Museum and its exhibitions, visit www.bowers.org. For more information on the British Museum, visit www.britishmuseum.org.

Recommended Hokusai Reading

Two beautifully designed hardcover books on Katsushika Hokusai, replete with stunning images, are especially noteworthy for its essays. Both books were authored and edited by Timothy Clark, an honorary research fellow and renowned Hokusai scholar at the British Museum.

“Hokusai: The Great Picture Book of Everything” (British Museum Press) features 103 drawings that demonstrate the artist’s brush skills and remarkable attention to detail. Art lovers will enjoy Hokusai’s images of the natural world and stunning mythical creatures.

“Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave” (Thames and Hudson in collaboration with the British Museum) accompanies the museum’s exhibition and is a comprehensive exploration of Hokusai’s life and works, focusing on the artist’s final years. The book also includes the works of Oi, Hokusai’s youngest daughter. Essays by Clark, Alfred Haft, Angus Lockyer, Matsuba Ryoko, Asano Shugo and the late Roger Keyes, who was a leading Hokusai scholar, offer extensive insights on the artist and his environment.