Students from Terminal Island Elementary school, circa 1929. Chizuru Nakaji Boyea is pictured in the second row, fifth from the left.

Terminal Island was the end of the line for a community of prewar JAs.

By Gil Asakawa, P.C. Contributor

In the late 1800s, early Japanese immigrants, mostly from Wakayama, settled in Terminal Island, cradled by the Port of Long Beach to the east and San Pedro to the west, where they established a thriving fishing village, becoming known as master tuna fishers and establishing canning businesses. The tuna fishing industry was so important that to this day, the City of Los Angeles features an albacore tuna on its official seal as a tribute to the fish caught by Terminal Islanders.

Tuna Street, circa 1929

(Photos: courtesy of Paul Boyea and Terry Hara)

By the time World War II began, it was a tight-knit community of Japanese Americans that had a different spirit and culture from JAs in other parts of the Los Angeles area, including Little Tokyo and Orange County across the water. The more than 3,000 residents of the community affectionately called the area Furusato, or “hometown.”

But when Pearl Harbor was bombed on Dec. 7, 1941, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 two months later on Feb. 19, the JAs on Terminal Island were the first to be forcibly removed and relocated. In fact, even before the signing of EO 9066, they were ordered by the U.S. Navy to evacuate their homes with only 48 hours’ notice.

Tuna Street, circa 1942, after the forced removal of Japanese Americans to concentration camps and prior to mass demolition

The island was close to U.S. military installations including the Naval Station of Long Beach, and after Dec. 7, the FBI immediately arrested community leaders — mostly men, including Buddhist priests. Most of the community — women and children at first were separated from the men for up to months — were primarily imprisoned in American concentration camps at Manzanar, Poston and Gila River.

The fishing village itself was mostly razed, and the island turned into a military and industrial hub. After the war, the JAs never returned to live on Terminal Island and settled in nearby Gardena, Long Beach, Torrance or Little Tokyo in downtown Los Angeles.

Over the decades since, most JA histories have focused on the better-known concentrated Japantowns in San Francisco, San Jose and Los Angeles or on the 10 camps where the communities were incarcerated. Terminal Island isn’t well-known even among JAs, except for a 2024 hardcover book by Naomi Hirahara and Geraldine Knatz, Ph.D., titled “Terminal Island: Lost Communities on America’s Edge” that shines some much-deserved light on that fishing village’s history.

The Nakaji family, circa 1932. Pictured are (first row, from left) Hiromichi, Ritsuko, Hideyo and Sadahyaku (father) and (second row, from left) Chizuru, Chiyeno (mother) and Tooru. (Photo: Courtesy of Paul Boyea)

There is a memorial to the Japanese Americans’ lost history at “Fish Harbor” on Terminal Island, across from the San Pedro Arts and Cultural District at 1124 S. Seaside Ave. It was placed in 2002 by the Terminal Islanders Club, a group of former residents and their descendants.

Ryono Café and Dr. Fujikawa’s office, located at 701 Tuna St.

The Terminal Islanders Association was formed in 1971 to preserve the unique cultural legacy of the fishing village. One of its presidents was Minoru Tonai, who was also a leading figure in the Amache Historical Society; he was incarcerated at Amache when he was a teenager. Tonai died in 2023.

Two current leaders of the organization, Terminal Islanders Association President Terry Hara and Preservation Committee Chair Paul Boyea, are working with the organization and the Port of Los Angeles on ways to further preserve the legacy and heritage of the original fishing village, even though very few prewar buildings still stand.

Both men’s families were part of the Terminal Island community, though they grew up after the war in Long Beach.

Hara is notable separate from his family’s roots because he was made the first deputy chief of the Los Angeles Police Department in 1980, the first Asian American to attain that rank. He retired in 2015. Boyea is retired from the textile and fashion industry.

The monument is a popular destination for curious visitors, and Hara and Boyea say they find themselves speaking to people there who may have heard about it or were on a school field trip.

“Paul and I give presentations,” Hara said. “There were students there just recently, and every time we go there, whether it’s just business or to discuss some things, we find that there are visitors that come to the monument and learning about kind of why it’s there and the background. We’re there to help them understand and then tell the story for our new audience, which is fantastic.”

Hashimoto Co. chandlery store, located at 757 Tuna St.

There is also an exhibit about the Japanese Fishing Village in the Maritime Museum in the ferry boat terminal on the San Pedro side of the island.

Still, if the incarceration is relatively little-known, the Terminal Island experience is almost forgotten except for the few that show up at the memorial or are involved in the Islanders Club. It’s up to Hara and Boyea, as well as others who share their passion to keep the memories alive.

“My grandfather was a superintendent at one of the canneries,” Hara said. “And all the males on Terminal Island after Dec. 7 were all sent to different locations and just the wives and the children were left to basically take care of getting everything together because the order was to evacuate or to leave within 48 hours. The Terminal Islanders were the first group that got evacuated.”

And after the war, even though farmers and business people might have lost everything, the Japantowns remained intact (Little Tokyo was settled by African Americans during WWII and called “Bronzeville”) but the village had been demolished, so, Hara added, “there was no place to return to.”

Nanka Co. Dry Goods store, located at 700-702 Tuna St., was established in 1918.

The homes and businesses had been demolished for national security reasons, Boyea and Hara understand, but Hara noted, “It was the military and the government’s paranoia.”

Today, it is one of two remaining buildings in Terminal Island.

What’s left today, besides the memorial dedicated in 2002, are two buildings from the prewar era that are in danger of being leveled for new buildings today. The Islanders are trying to find a way to preserve and protect them from that paranoia of the past.

“We have to have hope,” Hara said. “If we don’t have hope, if we allow what the Port of Los Angeles is considering, you know, once things are removed or demolished, then the memory also goes with it. And we’d like to keep around things that were around culturally, speaking of what existed, and have people think about why it existed. And for the younger generation that we meet — so many people are not aware of the Terminal Island story, right?

“Our hope is to preserve the buildings, the last piece of what was part of the Japanese village on Tuna Street to repurpose and help contribute cultural value,” Hara continued. “Our hope is to reutilize it to have a positive contribution for the young generation as evidence of what existed back then.”

Boyea offered that the Club isn’t alone in this effort. “One thing I wanted to mention is that we’re very serious about this endeavor,” he said. “They know that we’ve formed a coalition, and we have, you know, a lot of strong advisers on the coalition, whether it’s the LA Conservancy, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Asian and Pacific Islander Americans in Historic Preservation, Central San Pedro Neighborhood Council, which is more of a local group, the council member for the district on the L.A. County Board of Supervisors. So, there’s a lot of different people that we got involved, and we’re treating this like a business, putting together a business plan. So yeah, it’s not haphazard. They know how serious we are about this.

“And that’s the way we’ve been going about our presentations with them on the few presentations that we’ve had,” Boyea continued. “So, this is something that’s going to be very interesting as we go forward. Like Terry said, we have to have hope.”

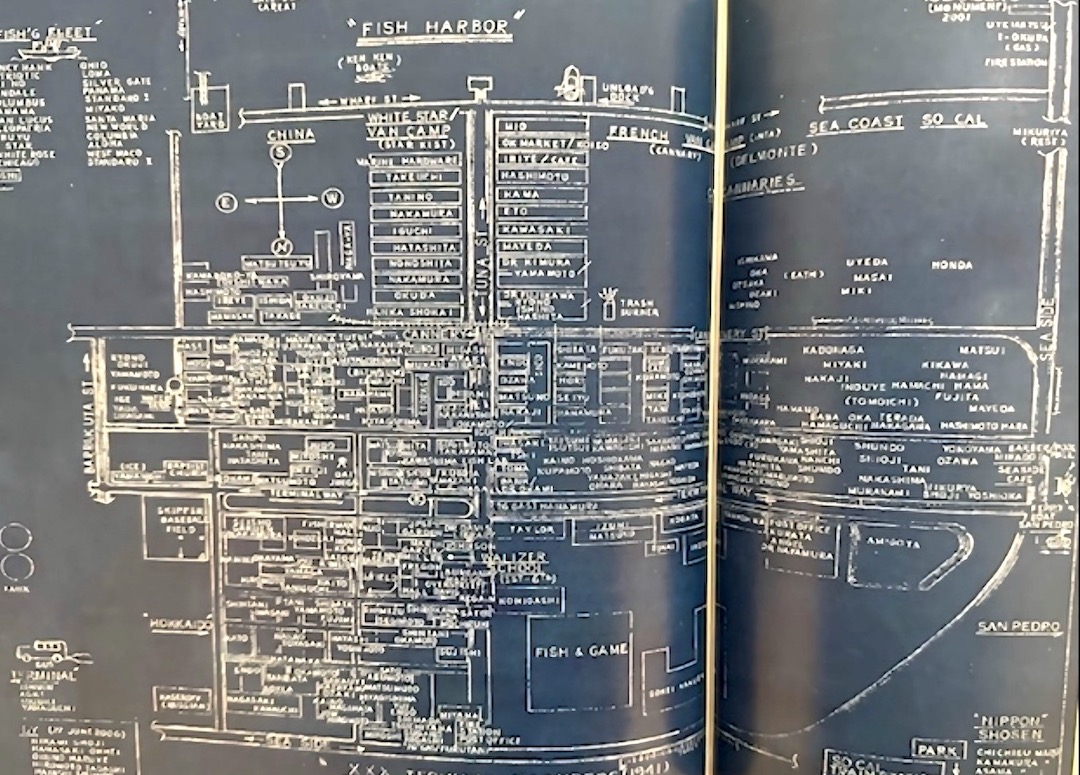

Terminal Island resident map, circa 1941 (Photos: Courtesy of Paul Boyea and Terry Hara)