1st Lt. Jake Hearen hands Sonoe Inai a folded American flag to honor her late husband,

100th Battalion veteran Haruo Inai, whose remains were reinterred at the Los Angeles National Cemetery on on April 4. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

With providence, help from friends and the internet, Sasha Mori ensures

that the remains of her uncle, a 100th Battalion veteran, find a place of honor.

By George Toshio Johnston, P.C. Senior Editor

Although “final resting place” implies the site where one’s earthly remains get put forever, it turns out that is not always so.

Consider the case of former Army Pfc. Haruo Inai, a decorated member of the segregated 100th Battalion’s C Co., who died at 89 on Feb. 22, 2010. Although his cremated remains were interred a few weeks later on April 10 at Los Angeles’ Evergreen Cemetery with deceased family members, some 15 years later, his urn would take an 18-mile journey to a different final resting place.

Urn containing cremains of Haruo Inai before the April 4 reinterment. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

How and why that happened would also become a more than two-yearlong journey of a different sort for his niece, Sasha Mori, who, like her aunt and Haruo Inai’s widow, Sonoe Inai, is a native of Japan. Mori’s father was Sonoe’s youngest brother.

One might, however, say that Mori’s journey with regard to having the remains of her uncle moved from a gravesite that did not even include his name to a new final resting place at the Los Angeles National Cemetery in Westwood, Calif., began when she immigrated to the United States in the mid-1980s.

Like many native Japanese, when she first arrived, Mori did not know much about the Japanese American community of which her Uncle Haruo was a part. She knew even less about what many Japanese Americans experienced during World War II, not just the mass removal and incarceration but also the exemplary military service of the Nisei who fought in Europe as part of the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team or served in the Military Intelligence Service across the Pacific.

Over her decades of living in America, however, Mori did learn some of that history, though not from her uncle. “Haruo was a pretty private person,” she told the Pacific Citizen, and he shared with her nothing about his military service.

Although most in the so-called “Greatest Generation” have been generally characterized as being tight-lipped about their WWII service, they were Chatty Cathies compared with most of their taciturn Nisei cohort.

Stories of their Nisei wives and Sansei offspring not knowing the details of the military service of their spouses and fathers are not uncommon. That was Haruo Inai.

Haruo Inai’s CIB (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Nonetheless for Mori, that someone like her uncle, who earned the right to wear the Combat Infantryman’s Badge and was awarded the Purple Heart after being gravely wounded — the bullet that hit him on “29 Oct 44” (according to his honorable discharge papers), narrowly missing his heart and occurring during the bloody, high-casualty Rescue of the Lost Battalion — would end up in an unmarked grave as his final resting place just didn’t sit right.

❖❖❖

Reconstructing the life of a man who didn’t share much about it while he was alive 15 years after his death can be a tall order.

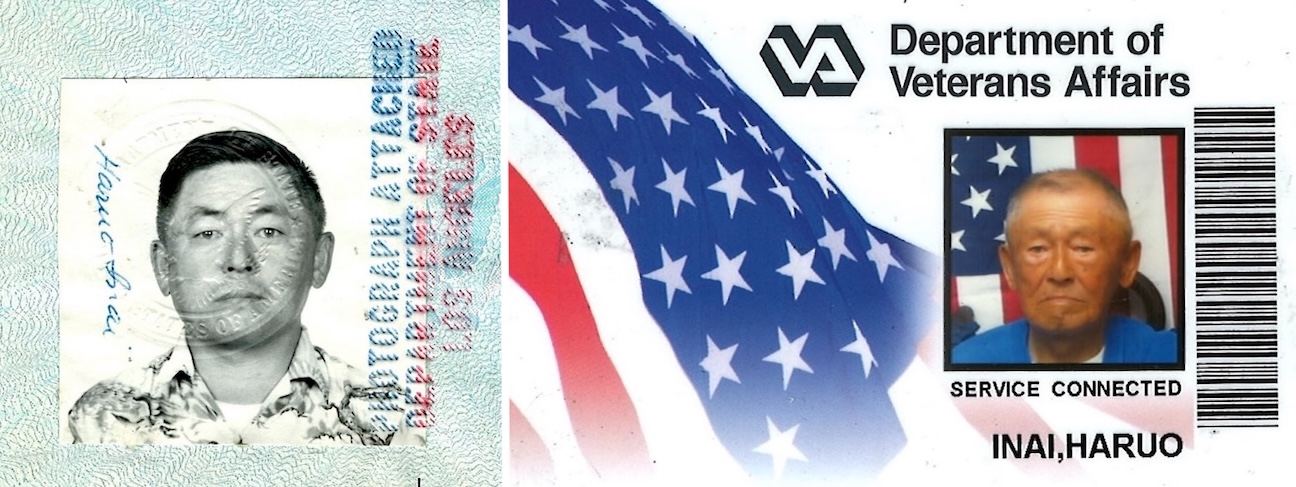

For Haruo Inai, there aren’t many family photos of him, in uniform or from civilian life, just images from identification documents.

These photos of Haruo Inai are from his passport and VA identification card.

There is also no oral history that was recorded as part of the Go for Broke National Education Center’s Hanashi project. He and Sonoe had no children who might have, in their later years, been able to glean some details about his life.

At 94, his wheelchair-bound widow, Sonoe Inai, whose English is limited, and whose stamina is likewise, as would be expected of someone of her age, doesn’t seem to have much to share as far as any stories he may have told her —“may have” being the key words, since his Nihongo was as limited as her Eigo.

“Haruo’s Japanese was also very broken Japanese,” said Mori, regarding how he and his wife communicated. “I guess when you live with the person for a long time, you kind of read from the body language, right?”

Furthermore, most of his fellow vets with whom he served and who might have been able to share something about him are, like Haruo Inai, deceased.

Nevertheless, there exist records that reveal some facts about his life. He was born in La Habra, Calif., and his formal education ended in the 10th grade in 1938 at Fullerton High School.

Haruo Inai’s military medals and ribbons that were saved from being discarded (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Before joining the Army, he was employed by the La Habra Citrus Assn. as a harvest hand, a lemon and orange picker. He stood 5-feet, 1-inch tall and weighed 125 pounds when he left the Army. He had three younger siblings: a brother, Tomio; a sister, Yasuko; and youngest brother Minoru, born in 1928. He died in 1930, on the same day as his mother, Tatsu, leaving Kumeji Inai a widower. Haruo’s living siblings and Kumeji would be incarcerated together at the Poston War Relocation Authority Center.

According to the Final Accountability Roster for Poston, the three of them were sent there beginning in May 1942. In 1944, Tomio left for Poston for Fort Douglas, Utah, to join the Army; he would be assigned to the 442nd Regiment’s H Co. and earn the rank of staff sergeant. In February 1945, Yasuko left camp for Chicago; Kumeji followed in August.

Haruo Inai, meantime, was inducted into the Army on Jan. 6, 1942, which explains why he didn’t join his family at Poston. He received his honorable discharge on Nov. 9, 1945. In between, he served with the 100th Battalion in Rhineland, the Northern Apennines and the Po Valley.

In addition to earning the CIB and being awarded the Purple Heart, Haruo Inai also received a Good Conduct Medal, Division Commendation and a Distinguished Unit Badge. Postwar, like scores of other Japanese American men, Inai made a living as a gardener in Los Angeles.

❖❖❖

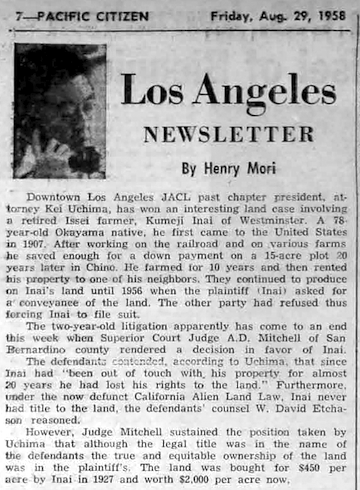

To learn how Haruo Inai met and married Sonoe Tsuboi, one has to backtrack to his Issei father and piece together his story, too. Before emigrating to the U.S. in 1907 at around age 28, Kumeji Inai was born in 1879. One source has his birthplace in Shikoku (the smallest of mainland Japan’s four main islands); another source — an article written by Henry Mori in the Aug. 29, 1958, issue of the Pacific Citizen — has him as an “Okayama native.”

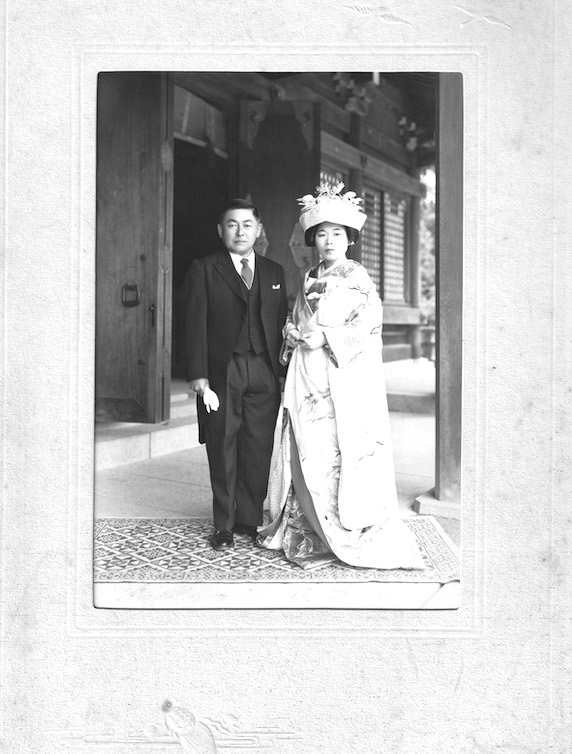

Regardless, Kumeji Inai used a nakōdo, or matchmaker, to help his son, Haruo Inai, find a Japanese wife. Here, it gets a bit convoluted. According to Sasha (not Henry) Mori, her father had heard about Haruo Inai’s wife search via this same matchmaker. That of course begs the question: Why did Sasha’s father, originally born Tomozo Tsuboi, have a matchmaker?

Wedding photo of Haruo and Sonoe Inai (Photo: Courtesy of Sasha Mori)

That is because he was “adopted” as an adult into the Mori family, a somewhat common practice in Japan known as mukōyoshi that can occur when a family without a male heir to continue the family line adopts an adult male, carefully vetted, from another family to become a member of the son-less family.

So, via his matchmaker, Tomozo Mori became involved in helping Haruo Inai find a wife — and that would be his older sister, Sonoe Tsuboi. A single woman, Sonoe was still living at her mother’s home, where the second-eldest brother, who, under Japan’s patrilineal conventions, would become head of the family. (The original eldest brother was killed in the war.)

With her brother’s wife and children in the house, Sonoe’s options were limited. “She was totally becoming like [an] outsider,” Mori said. Family members urged Sonoe to marry Haruo Inai and move to America for a new life with her new husband — and that was what happened.

❖❖❖

After moving to Los Angeles, Sasha Mori was, while also herself staying occupied with making a living, charged by her father to keep in touch with and help whenever possible his eldest sister — her Aunt Sonoe and her husband, Uncle Haruo Inai.

This article from the Aug. 29, 1958, issue of the Pacific Citizen summarizes a real estate lawsuit involving property owned by Kumeji Inai, father of Haruo Inai (Photo: Pacific Citizen Digital Archive)

One of Sasha Mori’s memories from 1989 that planted a seed that began her interest in her uncle’s life came from a talk with her landlord, himself a WWII veteran. Once when Sonoe and Haruo came to visit Sasha, the landlord, who had been stationed in postwar Japan, struck up a conversation with Haruo to practice speaking some of the Japanese language he had picked up.

Instead, however, they spoke in English and with their military service in common, Haruo actually revealed a bit about what he had experienced in the 100th Battalion. Later, Mori’s landlord told her that her uncle was “a brave man” who had been gravely wounded in the war and had been awarded the Purple Heart. “I did not know what ‘Purple Heart’ was but only knew it was something important,” she recalled.

After Haruo’s death in 2010, Sonoe Inai continued living in the Westminster, Calif., house where she and Haruo resided. Sasha Mori continued to keep in touch with her aunt. But as the years went by, it became evident to Mori that her aunt, who mostly kept to herself, needed to move to a place where she could get assistance just living her life.

February 2023 would be a turning point. That was when Sonoe would need to renew her driver’s license, a chore that Mori had doubts her elderly aunt could successfully complete — or whether it was wise to do, even if she did pass the test. Instead, Mori convinced her aunt to move to a senior-care facility and sell her home.

In October 2022, Mori began that process by enlisting the help of her friend, Cindy Kawata, a real estate broker. That also started the process of going through Sonoe’s — and Haruo’s — belongings to see what should be kept or discarded. It was then when Kawata came across all of Haruo’s military-related paraphernalia: documents, medals, ribbons, etc.

It was the next turning point in Haruo Inai’s posthumous journey: Sasha Mori made sure to save all of it, including his Purple Heart.

That same month, Mori and Sonoe Inai visited the Inai family gravesite at Evergreen Cemetery. It was there where she discovered something curious about the family plot: The headstone only listed Tatsu, Kumeji and Minoru Inai. Although his cremated remains were buried in the plot, no one would know because the name Haruo Inai was not inscribed on the stone. To Sasha Mori’s mind, something had to be done.

❖❖❖

A devout Christian, Sasha decided to reach out to a member of her church who had served in the military for advice and to learn whether her late uncle was entitled to being interred — or reinterred, in this case — at a veterans cemetery.

The short answer: Yes. Also fortuitous: Mori’s church friend also introduced her to his friend, Gail Johnson, a Gold Star mother who lost her son in 2007, for help. She reached out to Cuauhtemoc Meza, aka Temoc, director of the Los Angeles National Cemetery, the large, scenic burial ground for U.S. military veterans just east of the 405 freeway in Westwood.

But just getting the greenlight was not enough.

Before anything could begin, there was the requisite paperwork that needed to be completed to do such things as obtaining permission to disinter Haruo’s urn. Sonoe also wanted half of her late husband’s remains to stay put, with the other half interred at LANC. Add to that the new job that Sasha had just started in spring of 2023; its demands would put any action on hold for two years.

By March 2025, things began moving again. Mori was able to get a date for the service at the LANC chapel, followed by the reinterment on April 4.

Sonoe had also changed her mind about dividing her late husband’s cremains, deciding that having his entire urn transferred would be OK, eliminating another possible impediment.

Sasha, meantime, decided to forgo the bagpipes for the service with a more personal touch: She would play the flute in a wind quartet, selected from the Palos Verdes Symphonic Band’s First Responders in Music, of which she is a member.

From left: Brian Smith, Sasha Mori, Max Miller and Len Pagarigan (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Mori also took to her computer to do a little internet research about the 100th Battalion/442nd Regimental Combat Team and found a video news clip featuring Go for Broke National Education Center President and CEO Mitch Maki.

She then found his profile via LinkedIn and contacted him that way, inviting him to the service. Fortuitously, even though Maki later told her that he typically doesn’t check his LinkedIn account, he just happened to — and called Mori. Both he and GFBNEC Director of Programs and Engagement Kurt Ikeda accepted her invitation to attend the ceremony.

Clip from a Pacific Citizen article from Nov. 25, 1944, listing a combat injury sustained by Haruo Inai. (Photo: Pacific Citizen Digital Archive)

Mori’s internet research also led her to the Pacific Citizen’s digital archive, where she found an article from the Nov. 25, 1944, issue. In an article with the headline that read “22 Japanese Americans Killed, 79 Wounded on French Front,” she was stunned to see her uncle’s name was listed among the wounded — and amazed to learn the newspaper was still being published.

So it was that an invitation to Haruo Inai’s reinterment ceremony was also made to the Pacific Citizen.

Haruo Inai’s gravesite marker (Photo: Courtesy of Sasha Mori)

In the months since her uncle’s reinterment, complete with a stone marker, Mori has mulled over the sequence of events of that led to that point. Prior to wondering why her uncle’s name was missing from the family plot’s gravestone, Mori says she “did not know anything about the 442nd.” Then, in her conversation with Maki, when he mentioned the Rescue of the Lost Battalion, her uncle’s role in that and the wound he sustained, she told the Pacific Citizen: “I even did not know the words, but somehow the words sounded so heavy, and I thought, ‘Oh, my God, I’m so embarrassed.’

“So then I started to look up the history,” she continued. “And then I think that was the time I Google-searched Haruo’s name with ‘442nd’ and then found him in the Pacific Citizen. He was meant to be discovered by me.”

Haruo Inai’s honor was finally restored, and his final resting place had his name on a stone marker. One might even say that Inai was no longer inai.

Speaking on Memorial Day, not long after the reinterment ceremony, LANC’s Meza addressed the gathering and said this about Haruo Inai:

“On April 18, 1945, Pfc. Haruo Inai was recognized for superior performance in the line of duty. Because of Pfc. Inai’s actions and service to our country, we live free today. It’s great Americans like him who are the reason why we have the liberties to do simple things in life.”

Attending Haruo Inai’s reinterment are (from left) Kurt Ikeda and Mitch Maki of Go for Broke National Education Center; Los Angeles National Cemetery Director Cuauhtemoc Meza; Brian Smith; Sasha Mori; Max Miller; Sonoe Inai; Len Pagarigan; and Cemetery Administrative Specialist Pablo Agrio. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)