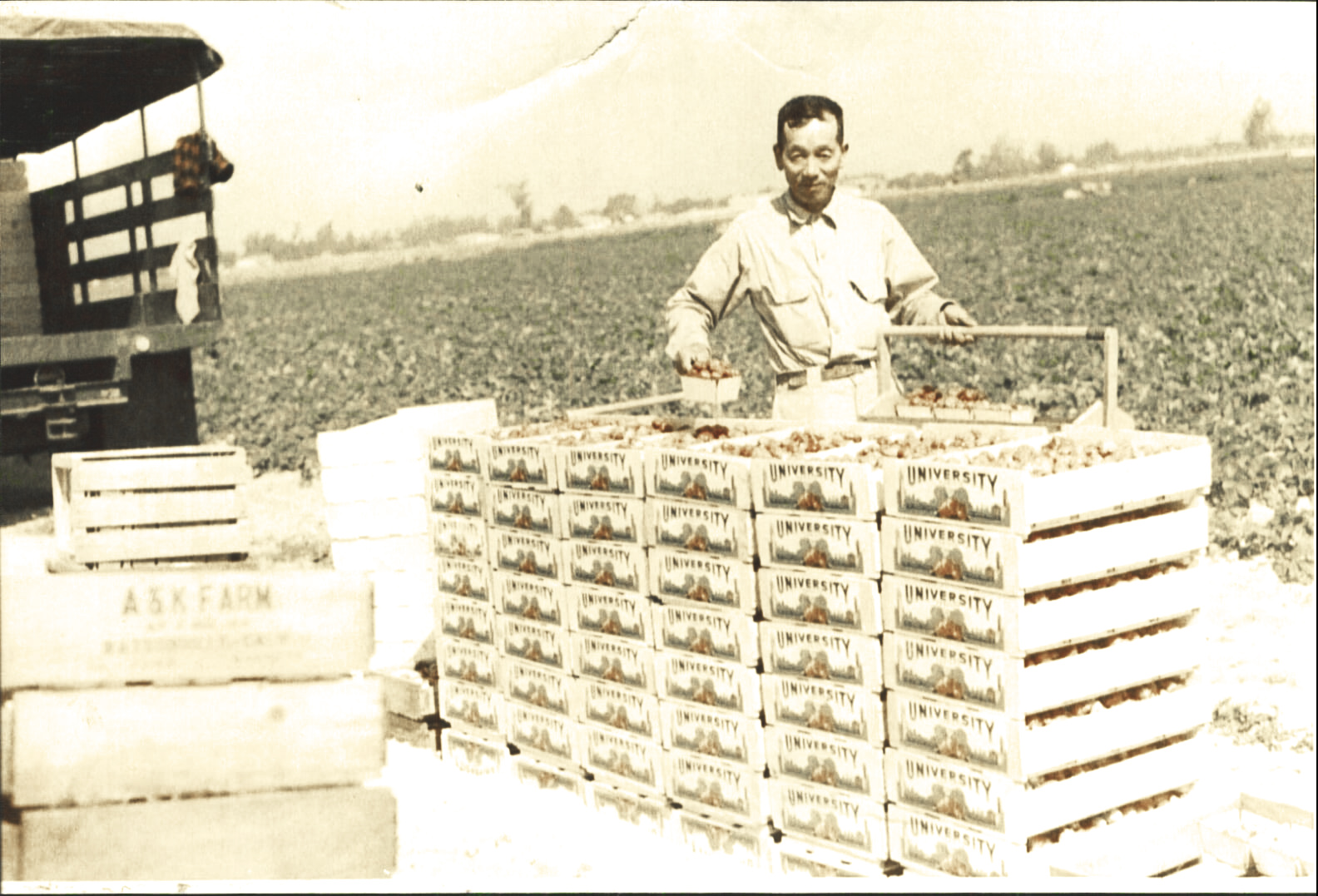

Seima Munemitsu with crates of strawberries from his family farm prewar (Photo: Courtesy of Janice Munemitsu and Chapman University)

The Japanese American family behind Mendez v. Westminster: California’s first successful desegregation case

By Annie Tang, Special Contributor

Many Orange County, Calif., schoolchildren know the name “Mendez.” After all, the iconic name is front and center of the landmark civil rights case that desegregated several of the county’s public schools in 1947, preceding the 1954 Brown v. Board case on a national level.

The Mendez family, one of five Latino families that challenged several school districts in the county on their practice of Mexican-only schools, had their name immortalized in history. But the Mendezes would not have been able to lead the legal charge if it was not for another family of color, the Munemitsus, the Japanese American farming family behind the story of Mendez v. Westminster.

The Munemitsu Family Comes to America

The Munemitsu family. Pictured are (front row, from left) Namio (Seima’s stepmother), Kazuko, Akiko, Masako and (back row, from left) Tad, Saylo and Seima. (Photo: Courtesy of Janice Munemitsu and Chapman University)

The first Munemitsu to arrive in the United States in the early 1900s eventually made his way to the South Bay of Los Angeles County, working as a hired laborer on a strawberry farm. These were the same farming skills he would later impart on two more generations of Munemitsu men and women.

The Japanese were common fixtures of rural life in Southern California, but they suffered through the indignities of barriers to citizenship and homeownership due to local and federal xenophobic legislation.

By 1931, the Munemitsu clan eventually migrated from the South Bay area to rural Orange County, Calif., where they acquired a farm in the next year. This generation was now led by patriarch Seima Munemitsu and his wife, Masako Morioka Munemitsu, with their boys, Seiko and Saylo, and twin girls, Kazuko and Akiko, in tow, as well as a few other extended members of their growing brood.

Seiko, or “Tad,” as he was affectionately known by loved ones, legally owned the farm as an American-born citizen on behalf of his parents, a privilege Seima and Masako were not able to enjoy themselves.

This was the case with many first-generation Japanese who immigrated to America and were not able to own land in their name, due to the Alien Land Law of1913. Many opted to purchase property in the names of their children in order to keep land in the family, just as the Munemitsus did.

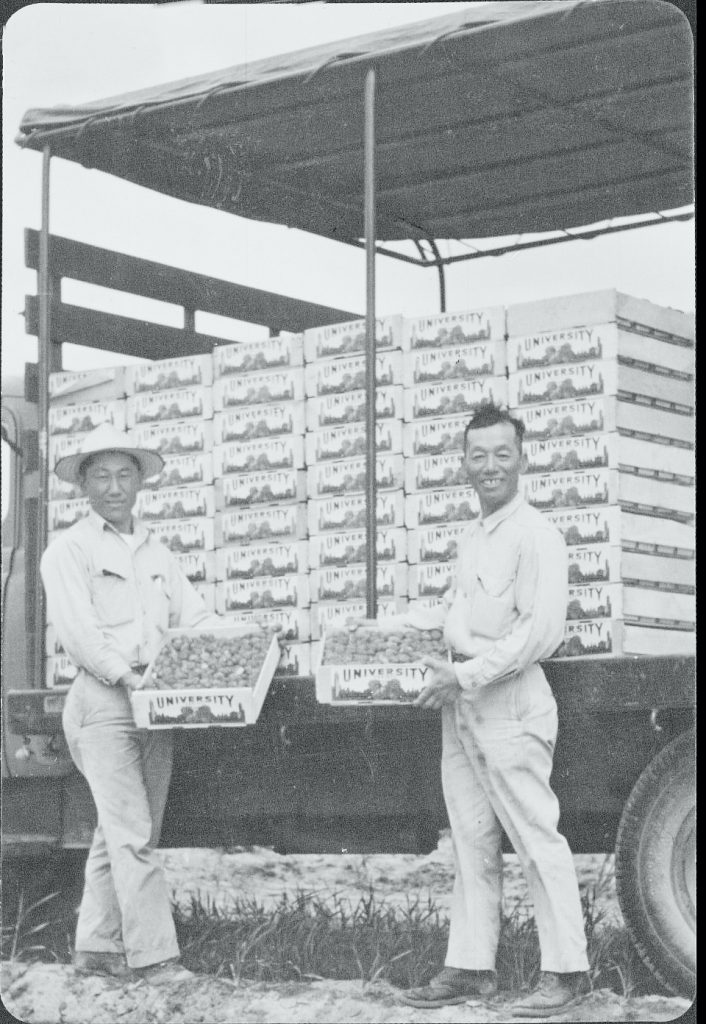

Tad (left) and Seima with their strawberry harvest (Photo: Courtesy of Janice Munemitsu and Chapman University)

Owning a 40-acre farm, the clan would be known as one of the longtime strawberry growers in Orange County.

The Dec. 7, 1941, Imperial Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor would implode the foundations of the Munemitsu family and other Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. With Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1942 anti-Japanese Executive Order 9066, ordering the incarceration of about 120,000 ethnic Japanese living in regions near the Pacific Ocean, the Munemitsus would be separated and interned.

Seima, known as an influential leader in the Japanese community, was arrested first in 1942 and sent to incarceration camps administered by the Department of Justice in New Mexico and then Colorado.

These DOJ camps were known to hold community leaders, political dissidents and religious leaders. They were also purposely cordoned off from their families and other relocation centers, so that their presence would not incite rebellion among the population.

Days after Seima was arrested, the rest of the family — Masako, Tad, Saylo, Kazuko and Akiko — were sent to the Poston War Relocation Center in Poston, Ariz. Tad and Saylo were young adults, while the twins were only in grade school.

With siblings who were underaged or attending school, and his mother and grand- mother unable to work, as the oldest, Tad took on the responsibility to work outside the camps to earn income for his family.

He took on employment in Colorado, with permission from his Indefinite Leave Clearance, a document that could only be obtained after signing a loyalty questionnaire. Many of those incarcerated had to make the same difficult decisions time and time again in the American concentration camps: attest to their American loyalty, to their country that incarcerated them — or proudly deny allegiance, but make the lives of themselves or their families more difficult.

During this time, Tad was still able to retain his family’s 40-acre farm in West- minster, thanks to their ability to lease it while they were away. Tad was one of the lucky few Japanese Americans who were able to continue owning their land holdings from afar while incarcerated. From 1944-46, in just those three short years, the lives of two clans — the Mendezes and the Munemitsus — would experience nation-changing events that would influence the narrative of U.S. history.

The Mendez Family Moves to Westminster

In 1944, Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez, successful cantina owners, moved with their children from Santa Ana, Calif., to Westminster. Renting out the home they owned in Santa Ana, they wanted to try their hand at farming and leased land from the Munemitsu family, who they met through a mutual friend.

Felicitas, born in Puerto Rico, and her husband, Gonzalo, born in Mexico, were no strangers to racial discrimination them- selves. Although Puerto Rican, Felicitas was essentially seen as “Mexican” by California racial standards, and her children with Gonzalo would also be seen as such.

When Gonzalo’s sister, on behalf of Gonzalo and Felicitas, tried to enroll her niece and nephews — Sylvia, Gonzalo Jr. and Jerome — into the whites-only 17th Street Elementary School in Westminster, she was indignant to find out that they would not be admitted.

Instead, only her own lighter-skinned children, with her European married surname, would be allowed enrollment. This racial exclusion would set off a civil rights battle against the school district led by the Mendez family.

When the Westminster School District Board refused to integrate Mexican American students as a whole into its whites-only schools, Gonzalo and Felicitas led community efforts to make change in the whole county. They did all this while continuing to cultivate the land they were living on.

Gonzalo began working with four other Mexican American families — the Estradas, Gomezes, Palominos and Ramirezes — to challenge the segregation policies. Together, the parents of these clans acted as plaintiffs and filed a lawsuit in federal court against multiple public school districts in Orange County.

Known formally as Mendez, et al v. Westminster School District of Orange County, et al, this federal lawsuit was argued in the U.S. District Court in Los Angeles in February 1946, where Judge Paul J. McMormick ruled in favor of the five families, stating, “A paramount requisite in the American system of public education is social equality. It must be open to all children by unified school association regardless of lineage.”

The school district did not see it that way and appealed the case, taking it all the way to the Ninth Federal Circuit Court of Appeals based out of San Francisco. There, too, the decision was upheld in April 1947, that the 14th Amendment was violated and students of Mexican descent were denied equal protection. Thus, Mexican-only schools were abolished in the Orange County school districts.

Where does the Munemitsu family play into this story? If it was not for the farming lease between Tad and Gonzalo, the case would not have existed. In 1944 and ’45, both men signed two one-year leases, which would allow the Mendez family to continue living on Munemitsu land and continue harvesting their asparagus.

If the Munemitsus had not been forced to leave their home, the Mendezes would not have been able to lease the farm, have their children unfairly rejected from enrollment at the local school and not have lead the legal charge for the civil rights of their community’s Mexican students.

Because of the injustices first inflicted on one family of color, injustices inflicted on another family, and multitudes of others, were able to be righted.

The Munemitsu Family Returns

With the August 1945 U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the death knell of World War II would sound, and so would the bell toll for the lives of hundreds of thousands of Japanese nationals.

Ironically, the incalculable loss and destruction felt by those in Japan would free those of shared ancestry across the Pacific: The Munemitsus, now joined by Seima, who was reunited with his family in 1944, left the Poston War Relocation Center in September 1945. Tad, working in Colorado, would be reunited with his family after they left Poston.

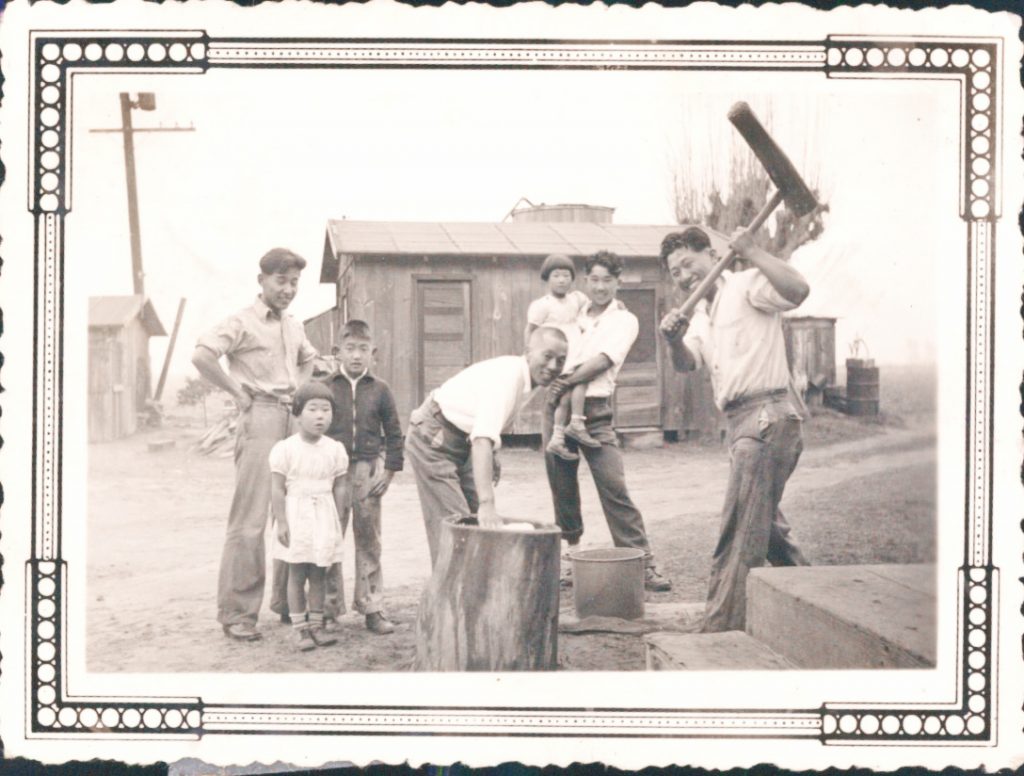

Gathered to pound mochi for New Year’s are (from left) a Munemitsu family friend and farm employee; Akiko; Seima’s stepbrother, Sam Munemitsu; Seima (with hand on mochi); Saylo holding Kazuko; and Tad Munemitsu (with mochi mallet). (Photo: Courtesy of Janice Munemitsu and Chapman University)

In the month prior, in August, Tad had signed a lease granting Gonzalo another year to work the farm. With the Munemit- sus returning soon, and the Mendezes living in the main house, a curious arrangement was agreed upon. According to the August 1945 lease, Tad requested the following:

“Buildings on the ranch are to be used as dwellings by the lessor [Tad Munemitsu] for the dwelling of his family or any per- son he designates” without cost or charge of rent. Also, lessee [Gonzalo Mendez] agrees to “furnish the lessor and his family with such work as is available on and around the farm herein leased and to pay the minimum of prevailing wages to each person so employed.”

In the last year the Mendez family lived on and worked this land in Westminster, so, too, did the Munemitsus in the first year of their return home. In fact, as the document relates, the Munemitsus worked for Gonzalo until the summer of 1946, likely living in the buildings their own former farmhands lived in. They may not have been living in their house, but they were home, and away from the Army barracks they were forced to inhabit for the past few years.

The Legacies of Two Families

The ruling of Mendez v. Westminster did not end segregation in public schools in all of California, nor in the country, but it contributed to its end.

Future U.S. Associate Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, then a lawyer representing the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, cited the Mendez case as precedent in the landmark 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board, which deemed racial segregation unconstitutional across the U.S.

Sylvia Mendez, one of the three Mendez children denied entry into her local West- minster school, to this day carries on her parents’ legacy in her advocacy of educa- tion for all children and in her retelling of her family’s story. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, presented by President Barack Obama, in 2011.

Janice Munemitsu, daughter of Tad Munemitsu, also helps carry on the Mendez v. Westminster legacy. She and Sylvia are currently involved in the Mendez Historic Freedom Trail and Monument in Westminster.

In collaboration with the Orange County Department of Education and the City of Westminster, this project will highlight the fight for justice for all people of color.

Annie Tang is the coordinator of Special Collections and Archives at the Frank Mt. Pleasant Library of Special Collections and Archives at the Leatherby Libraries of Chapman University. She manages the Munemitsu-Sasaki Family Collection. Special thanks goes out to Janice Munemitsu and former Special Collections and Archives Intern Kathy Morgan, who provided the research regarding the family papers.