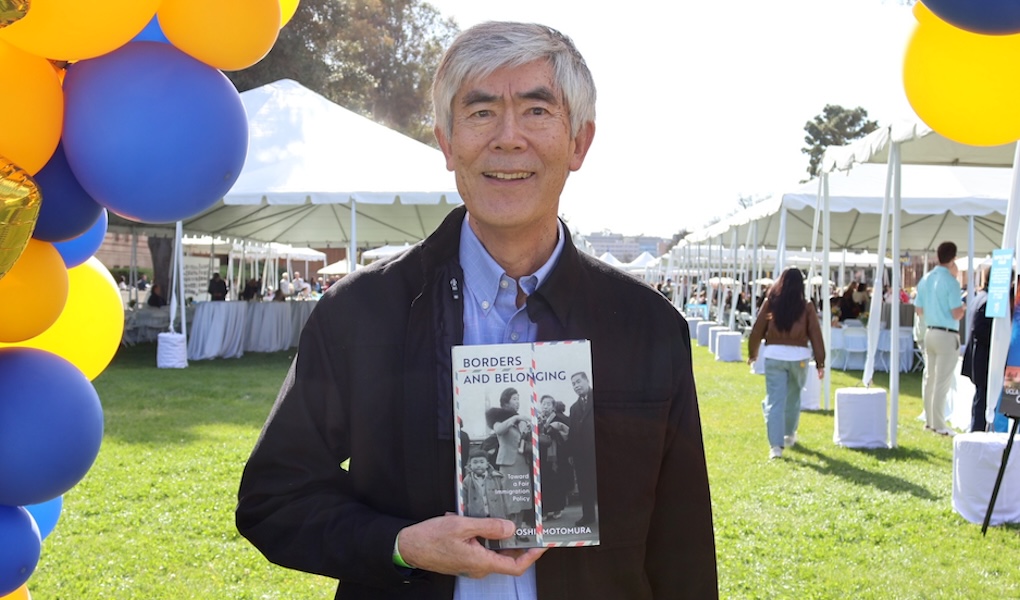

Hiroshi Motomura, the UCLA School of Law’s Susan Westerberg Prager Distinguished Professor of Law,

displays his new book “Borders and Belonging” at the law school’s 75th anniversary event on April 4. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Law Professor Hiroshi Motomura’s third book on the subject

arrives amid targeting of 14th Amendment, immigrant bashing.

By George Toshio Johnston, P.C. Senior Editor

In recent weeks, the president of the United States was reported to have stated that he was strongly in favor of “reverse migration,” wanted to “permanently pause migration” from poorer nations and end “federal benefits and subsidies for those who are not U.S. citizens,” as well as “denaturalize people ‘who undermine domestic tranquility.’” He also vowed to “deport foreign nationals deemed ‘noncompatible with Western Civilization.’”

This was followed by more invective, with the president writing on social media that he would send Somalis in America “back to where they came from.”

For context, the president made those pronouncements after an Afghan immigrant, here legally, traveled cross-country to New York City and shot at National Guard troops deployed by the White House, killing one and severely wounding another.

The president’s remarks about America’s Somali community, meantime, came after news of a large-scale grift in Minnesota — home to 84,000* people of Somali descent in the Twin Cities — in which many of the defendants charged with defrauding the government of Covid-19 relief funds meant to feed children were of U.S. citizens of Somali ancestry.

History tells us, of course, that Americans who share the president’s sentiments about fellow Americans who are not of the White Anglo Saxon Protestant or Northern European persuasion is almost as old as — maybe older than — the republic itself.

What is seemingly different in 2025, what is shocking and surprising, is that the nation’s commander-in-chief would and could make those statements so openly, so directly and so shamelessly.

❖❖❖

For Hiroshi Motomura, a professor at the UCLA School of Law, where he teaches immigration law, immigrants’ rights and the immigrant’s rights policy clinic, though he might be shocked at the blatant nature of the president’s recent statements, it would be a pretty safe bet that he was not all that surprised at what was said. “Everything that Trump is doing is from a certain playbook, and that playbook has been around for a while,” he told the Pacific Citizen.

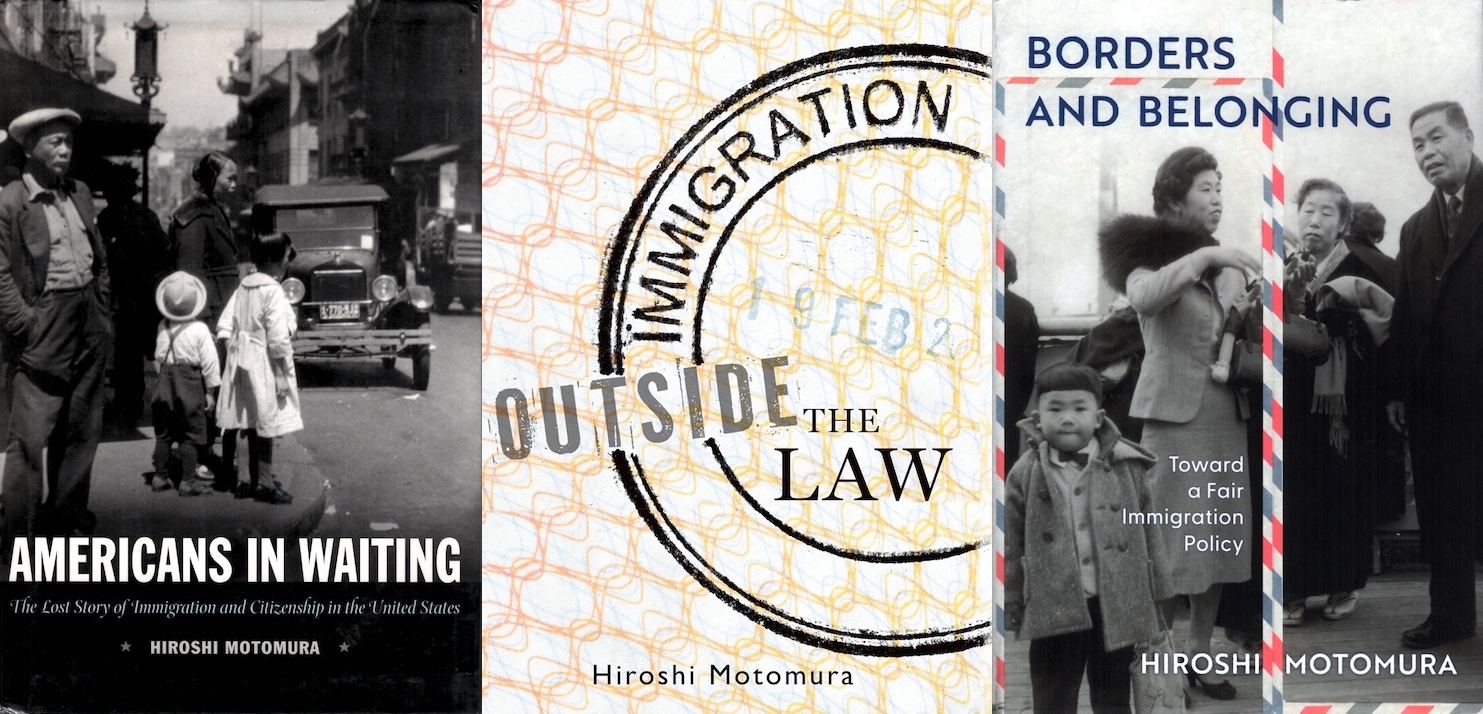

As the author of 2025’s “Borders and Belonging: Toward a Fair Immigration Policy,” it would also be a pretty safe bet that Motomura knows of what he speaks, with “Borders” as his third book on immigration law and policy. His first was 2006’s “Americans in Waiting: The Lost Story of Immigration and Citizenship in the United States,” and his second was 2014’s “Immigration Outside the Law.” (All three are published by the Oxford University Press.)

UCLA School of Law Professor Hiroshi Motomura has written three books on immigration: “Americans in Waiting: The Lost Story of Immigration and Citizenship in the United States” (2006),” “Immigration Outside the Law” (2014) and “Borders and Belonging: Toward a Fair Immigration Policy,” 2025.

But his award-winning books — “Americans in Waiting” won the Association of American Publishers Professional and Scholarly Publishing Award as that year’s best book in Law and Legal Studies, and “Immigration Outside the Law” won the same award for that year, along with it being chosen as the Association of College and Research Libraries’ Choice Outstanding Academic Title — are just part of Motomura’s bona fides.

Prior to joining UCLA School of Law’s permanent faculty in 2008 as the Susan Westerberg Prager Distinguished Professor of Law and serving as the faculty co-director of the Center for Immigration Law and Policy, Motomura was the Kenan Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He was also the Nicholas Doman Professor of International Law at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Also at CU Boulder, he was named the President’s Teaching Scholar, the university’s highest teaching distinction.

His other accolades: being named the Distinguished Teaching Award for Post-Baccalaureate Instruction at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and receiving the 2013 Chris Kando Iijima Teacher and Mentor Award from the Conference of Asian Pacific American Law Faculty. In 2014, he received the UCLA Distinguished Teaching Award and in 2021, the UCLA School of Law’s Rutter Award for Teaching Excellence.

As a visiting professor, Motomura has taught at Japan’s Hokkaido University, the University of Michigan Law School and was a guest researcher at the Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin.

The preceding is all the more impressive considering that early in his life, Motomura was for a time legally stateless. Perhaps that explains what motivated him to become the expert’s expert on U.S. immigration law.

❖❖❖

Unlike his brother, younger by six and a half years and born on U.S. soil, and therefore an American citizen from Day 1 of his life, Hiroshi Motomura’s journey to becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen was more convoluted and circuitous — and far different from his fellow Japanese Americans with whom he grew up in San Francisco.

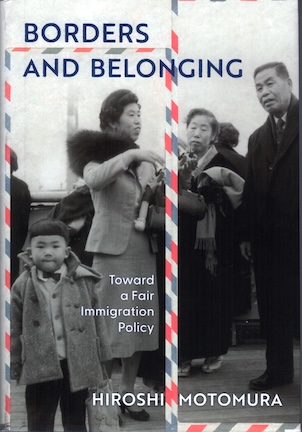

The iconic aerogram letter is a fitting design motif for Hiroshi Motomura’s third book.

The cover of his third book, “Borders and Belonging,” tells the beginning of that journey. Taken in 1957, it’s a photo that shows an overcoat-and-bow-tie-clad lad with a bowl-head haircut looking into the camera in the foreground with his mom in natty yōfuku (Western garb) and a traditionally garbed relative in the background.

That boy is Motomura, about to board the USS President Wilson at the Port of Yokohama, ready leave Japan with his mother for America, where his father had been born in 1925 in San Francisco. The cover’s design fittingly includes rectangular red, white and blue striping that is recognizable to anyone who remembers aerograms, a now-discontinued postage-paid air mail letter that could be written on, folded over and put into the mail. For those in his parent’s generation, the aerogram was the quickest and cheapest way to communicate between the U.S. and Japan.

That Motomura’s father had been born in the U.S. to Japanese parents, the husband of which worked for the Yokohama Specie Bank, was a key factor to how, more than 30 years later, he, his wife and young son would be able to emigrate from Japan at a time before the immigration reforms of the mid-1960s, when the quota for Japanese wishing to move here was less than 105 annually.

Although Motomura’s father was drafted into the Japanese army during World War II as a young man, fortunately for him he never experienced combat and postwar found employment as a houseboy on a U.S. military base during the Occupation.

Motomura’s mother, meantime, was from Yokohama; his parents met and married in the early 1950s and at some point decided to leave a war-devastated Japan for America. But there were complications to effectuating that plan. Despite his father having U.S. citizenship (thanks to the 14th Amendment and the Wong Kim Ark case), he had not been to America since 1930, when his family returned to Japan, and he spoke English as a second language.

So, as Motomura put it, the question became how, if you were Japanese and wanted to come to United States, would you do it when the quota for Japanese in any given year was such a miniscule number? Here, it gets a bit fuzzy, even for a professor steeped in immigration law and history.

❖❖❖

“It was an issue, whether his being drafted in the Japanese army was in effect, expatriating and would cause him to lose his American citizenship,” said Motomura, who added that fact might have scotched his father’s plans to “emigrate”/return to the U.S.

“He never told me about the details of this, but there were other people in his situation,” Motomura said. There was an attorney, whose identity Motomura does not know, who found that someone who had been drafted into the Japanese army but had never saw combat would be able to retain and confirm his U.S. citizenship. “I have inferred, although I’ve never seen this in writing, the cost of doing that was for him to make it clear that he was not a Japanese citizen.”

When Motomura’s father was cleared to return to the U.S. as a citizen, he entered a hotel-and-restaurant program at City College of San Francisco and became a cook, getting work at various hotels, including the city’s Plaza Hotel, and started saving money to bring his wife and son to America. At the beginning of this three-yearlong process, Motomura’s mother was pregnant with him, and he spent his first years in Japan.

This was, Motomura noted, when U.S. citizens could bring their spouses and children stateside outside the quota that restricted Asian immigration at that time.

And where did that leave young Hiroshi Motomura? He was born in Japan when his father was overseas at a time when Japanese citizenship was passed only through the father’s bloodline. So, he did not receive Japanese citizenship through his mother. As for getting U.S. citizenship through his father, that wasn’t possible either.

“The reason is that United States citizenship passes to a child born outside the United States from a U.S. citizen parent only if that U.S. citizen parent lives the United States for certain number of years, some of which have to be after the age of 14,” Motomura said, noting that because his father left the country at age 5, that did not apply.

“The particular combination of facts here meant that I was stateless,” Motomura said. “I had no citizenship, which is also unusual.” (He did, however, have a green card.) So, when his family and he went to visit his grandparents in 1968 at age 14-1/2, that meant he had to use a permit to enter the country, which is a travel document substitute, not a passport. “I couldn’t get a passport,” Motomura said. That would happen later, after becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen.

“The way I was able to naturalize is there’s a provision that allows a naturalization application to be filed by my father on behalf of the child for whom he did not fulfill the residency requirements at the time of the child’s birth. That was the situation.” After his father fulfilled the residency requirement, Motomura said his father “applied for my naturalization, and that’s how I got naturalized” when he was 15.

“I grew up in a community that had a lot of Japanese American kids, but their parents had been in the camps. They were classic Nisei. One consequence of this is my mother, and my father to some extent, but especially my mother, found herself not part of that community,” Motomura recalled. “I don’t think they treated her badly, but she would come back and say, ‘You know, I went to a JACL meeting, but those people, they speak funny Japanese,’ or ‘They don’t speak Japanese.’”

❖❖❖

Back to shock and surprise, it turns out that though Motomura may not have been surprised by the content of what has come out of the president’s mouth and from his social media postings when reacting to current events, he said what was surprising to him was “the vehemence, the perverse enthusiasm that the administration seems to come up with, ever more extreme things.”

Immigration — or illegal immigration — was, of course, one of the issues that candidate Donald Trump ran on that helped with getting him re-elected. Since his inauguration, that “perverse enthusiasm” would infamously include riot-inducing raids by mask-wearing federal agents that were supposed to target criminals but ended up dragnetting noncriminals, legal residents and U.S. citizens alike; stationing National Guard troops and even Marines within American cities; illegal deportations; transporting arrestees to prisons beyond U.S. borders; and attempts to circumvent the clear, plain wording of the Constitution’s 14th Amendment regarding birthright citizenship.

Although none of that had yet happened when Motomura turned in the final manuscript for “Borders and Belonging,” since it was before the outcome of the November 2024 general election, he nevertheless said he “knew what some of the issues would be.”

“Because the book was written before what’s happened since Jan. 20, I couldn’t address them in a way I can now address them more now. I can address them more directly because I can say, ‘Well, you know, this is what’s happening, and here’s how I look at it based on what I wrote in ‘Borders and Belonging,’” he said.

One of Trump’s first official acts after taking office on Jan. 20 was his issuance of Executive Order 14160, aka “Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship” (tinyurl.com/ec3e658r). It is a challenge to the legal concept of jus soli, Latin for “right of the soil,” which, under the 14th Amendment, confers anyone born on U.S. soil or under U.S. legal jurisdiction U.S. citizenship.

One of the fundamental, foundational legal cases that undergirds the application of the 14th Amendment also happens to be in the Trump administration’s crosshairs for challenge and reinterpretation. That case is the heretofore settled law of the 1898 Supreme Court case United States v. Wong Kim Ark.

❖❖❖

So it was that Motomura found himself with other Asian American legal experts on an April 16 panel titled “Advancing Equality: United States v. Wong Kim Ark,” sponsored by the Chinese American Museum.

Connie Chung Jo and Hiroshi Motomura at the April 16 panel titled “Advancing Equality: United States v. Wong Kim Ark” in downtown Los Angeles. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Held at the Historic Pico House in L.A. Chinatown, on the panel with Motomura were Dr. Linda Trinh Vo, professor emeritus at the University of California, Irvine; Connie Chung Jo, CEO of Asian Americans Advancing Justice Southern California; and Helen Zia, who was also the event’s keynote speaker. The special guest for the event: Norman Wong, none other than the great-grandson of Wong Kim Ark.

Norman Wong’s great-grandfather was the defendant in the landmark Supreme Court case that affirmed birthright citizenship. Wong’s mother, meantime, was incarcerated at an U.S. concentration camp for ethnic Japanese during World War II. (Photo: George Toshio Johnston)

Norman Wong also has a direct connection to another historical incident with legal consequences to Asians who came to America. Referring to how his great-grandfather had “endured jail time for citizenship challenges,” he mentioned how another relative of his had also been incarcerated for her ancestry.

“My mother also endured similar treatment. She, like my great-grandfather, was born in the USA. In 1942, she was forced, with her family and thousands of other Japanese Americans, to relocation camps, an experience that her family of 11 kept unspoken.”

For Motomura, Wong’s attendance was a fascinating continuity from the past to the present. “I had no idea that Norman Wong was around. It’s just really interesting to hear it from his perspective,” he said. “And, of course, he sees that case as central now in terms of birthright citizenship.”

On the topic of citizenship, Motomura said the following: “The real significance of Wong Kim Ark is partly in the register of understanding that this is an important landmark in the fight against racial discrimination in this nation’s history. But the other thing it does is it says there’s actually two ways you can think about citizenship.

“One is kind of the diploma version, the ‘If you’ve shown you’re an American, we’re going to give you diploma, we’re going to give you a merit badge’ and say, ‘OK, you’re a citizen.’ I think that’s how governments think about that now. That’s the reason why it’s hard to get naturalized in a lot of situations.

“I actually find that version of citizenship, in some respects, very troubling because what Wong Kim Ark did, that decision said, is, ‘No, we’re not going to just look at what you’ve done, but we’re going to look at the future of the country, and the last thing we want is a group of people who are living here but without full rights, at least without full formal rights.’

“What Wong Kim Ark stands for is the idea that it’s not just the merit badge that you get for your past life. It’s also the way you make the nation stronger in the next generation, and it’s a way you avoid having a generation of people who live here that don’t really have full legal rights.

“And so when we think about a lot of these citizenship rules, so much of the restrictions we’re seeing now are from the perspective of, ‘You don’t deserve it’ as opposed to the perspective of ‘What are the rules are going to make this country stronger and be more inclusive?’ And one of the best ways you can make a country more inclusive is to give people citizenship.

“What matters is not for the parents’ generation, but for the children. The fact that my father was a citizen was one of the ways that I felt like I belonged. . . . So, I think that a lot of the value of Wong Kim Ark in fighting the racial discrimination is to look ahead and not look behind.”

❖❖❖

As noted, one of the first official acts taken on Jan. 20 by the newly inaugurated president was to issue EO 14160, which was almost immediately challenged. As an executive order and not a constitutional amendment, such a challenge was inevitable.

Speaking at the aforementioned April 16 panel, Linda Trinh Vo explained what was in the executive order. “The current administration declared: ‘Children born in the United States will not be automatically entitled to citizenship if their parents are in this country illegally or temporarily,’” she said, noting that the EO was blocked by a federal court.

Also expected was that the Justice Department would appeal the ruling and that the issue would eventually wind its way to the Supreme Court to rule on the executive order’s legality. On Dec. 5, that happened when the high court announced it would decide whether the president had the legal authority, via executive order, to put restrictions on a constitutional amendment that addresses birthright citizenship. Published reports foresee justices issuing their ruling by the end of June.

Noting that he got himself “out of business of predicting what the courts will do,” Motomura at the panel nevertheless said, after noting the Supreme Court’s rightward turn over the last 10 years, “I can tell you a normal court — a normal Supreme Court even — would say, ‘This is ridiculous,’ but you know, to be honest, I’m just not sure what’s going to happen, although I have more confidence that this will be struck down than many other things that the administration is trying to do.”

Another topic that Motomura is unsure about is whether he will be writing a fourth book about immigration. “I’m definitely of retirement age,” he said. “On the other hand, I continue to work and have ideas. So, it’s hard to say. I do think that maybe the more substantive answer to your question is that each of these books responds to something I felt I left out of the prior book. Some of the answers to your question depends on how things evolve, in terms of how I assess this ‘Borders and Belonging’ book and what’s left out of it.”

Perhaps the answer to that question will be prompted by how the Supreme Court rules on EO 14160 in mid-2026. Regardless, it’s safe to say that the balanced, measured and nuanced perspectives that Motomura has provided on the issue of immigration will continue to be needed as America deals with new challenges on immigration that will inevitably arise from geopolitics, demographics and even the climate.

To view a video of Professor Hiroshi Motomura, visit tinyurl.com/ysm6kscr.

*Approximately 260,000 people with Somali origins live in the United States.