A ceremonial podium in front of the second memorial wall, containing a unified timeline of Native American and Japanese American history on the stie. (Photo: Rob Buscher)

The inaugural Snow Country Pilgrimage features the dedication of the Fort Lincoln Snow Country Prison Memorial, culminating a 25-yearlong effort led by JA community organizers to build relationships with Native leaders.

By Rob Buscher, P.C. Contributor

‘Sitting Bull would have been a renunciant.” These words have echoed in my mind for weeks since hearing them during the Snow Country Prison Pilgrimage in Bismarck, N.D., during the weekend of Sept. 5-6. Recounted by United Tribes Technical College archivist Dennis Neumann, the quote was attributed to David M. Gipp, the late former UTTC college president who was a member of the same Hunkpapa Lakota tribe that Sitting Bull once led.

The Snow Country Prison Japanese American Memorial was dedicated during the Snow Country Pilgrimage.

Of course, Sitting Bull was a resister in his own way, an influential spiritual leader of “free Indians” who defied the federal government’s orders to move onto the reservation. He was a freedom fighter who refused to give up his community’s ancestral lands, continuing the fight even when victory seemed impossible. This was a man who said, “If we must die, we die defending our rights.” When he finally did surrender to spare his people from starvation, Sitting Bull was the last man of his tribe to surrender his rifle.

Sitting Bull spent his final months of life held captive at the nearby Standing Rock Reservation, where he was then murdered by agents of the federal government for daring to resist the erasure of his culture and destruction of his people.

It is this honored ancestor that our own Nisei resisters were compared to and which gives a framework to understand the powerful expressions of solidarity and empathy symbolized by the newly completed Fort Lincoln Snow Country Prison Memorial.

The memorial wall contains all 1,901 names of those incarcerated at Fort Lincoln, carved into reclaimed roof tiles that originally adorned the prison buildings.

Photos: Courtesy of Rob Buscher

Led by Dr. Satsuki Ina, whose father, Itaru, was detained there during World War II, this memorial is the culmination of a 25-year effort by Japanese American community organizers to build relationships with the Native leaders of the tribal college.

Dr. Satsuki Ina’s father, Itaru, was detained during WWII at the Snow Country Prison.

Built on land gifted to Japanese Americans by the United Tribes, the memorial was designed by MASS (Model of Architecture Serving Society) Design Group, an international design collective with members in 20 countries that incorporates social justice into its architectural practice.

Set inside the courtyard of a former prison building turned into college classrooms, the memorial features two curved walls constructed from recycled roof tiles that covered the prison during WWII.

One wall features a timeline of the indigenous peoples of North Dakota and also incorporates the history of Japanese American incarceration in the region. Opposite is a longer wall with the names of all 1,901 inmates of Japanese heritage.

Layered with symbolic meaning and sacred images referencing both Japanese and Native cultures, the memorial’s core design team included Jeffrey Yasuo Mansfield, a mixed-race Yonsei, and Joseph Kunkel, a member of the Northern Cheyenne Nation.

Traveling to attend the memorial dedication during the inaugural Snow Country Pilgrimage, this was my first time in the state of North Dakota. Almost exactly 20 years ago in July 2005, I drove through South Dakota as part of a cross-country road trip after graduating high school — from Connecticut to California and back.

A view of the memorial drum circle

It was a coming-of-age trip of self-discovery as I explored regions of the country that were previously unknown to me before moving abroad for college. Of the middle states I traversed, South Dakota left the most memorable impact as I watched the great plains disappear into the rolling foothills of the Rocky Mountains midway through the state.

That was the first time I visited a reservation, and at the age of 17, I realized how little I knew about Tribal Nations in the U.S. These topics were largely excluded from U.S. public school curriculum by design, to keep us ignorant to the ongoing cultural genocide and erasure of Indigenous histories. By limiting our knowledge of tribal communities, the government further legitimizes our nation’s claim to their territories as a settler-colonial state.

Over the two decades since then, I have traveled the far corners of this country and come to know Native American communities in the context of pilgrimage to other confinement sites located on their ancestral lands.

In each region, the relationships are slightly different between Japanese Americans and Native communities, but they are generally positive. In some cases, there is direct collaboration, perhaps epitomized by the Amache Alliance Youth Ambassadors Program, which brings together young Japanese Americans with Cheyenne and Arapaho youth at both the former WRA camp and site of the Sand Creek Massacre during its annual pilgrimage.

Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation also has a longstanding relationship to the Apsáalooke, commonly known as the Crow Nation, including one member of their its staff who is a recognized member of the tribe. Poston Community Alliance even has a small section in the Colorado River Indian Tribes Museum in Parker, Ariz.

The Snow Country Pilgrimage coincided with UTCC’s 55th annual International Powwow, one of the largest in the country.

What excited me most about this trip was the prospect of engaging with members of the United Tribes of North Dakota and learning more about their histories. Participants were able to do so because the Snow Country Pilgrimage was deliberately planned to coincide with UTTC’s 55th annual International Powwow — one of the largest in the country with an estimated annual attendance of around 30,000 people from more than 100 tribes.

The Bismarck-Mandan metro area straddles either side of the Missouri River on the unceded lands of the Mandan people who since time and memorial have been the caretakers of this region. These lands were some of the last strongholds of the Plains Indians as they were displaced gradually northward and westward over decades of conflict with the joint colonizing forces of U.S. militarism and American capitalism.

The U.S. Army first established a presence in the Bismarck region in 1863, when it was first used as a forward operating position for the U.S. Cavalry. In 1872, the first Fort Lincoln was built about eight miles to the west of its current site, on the opposite bank of the Missouri River.

Stationed at the original Fort Lincoln was Gen. George Custer, who deployed from the site on his way to the Battle of Little Bighorn when his military occupation forces were decisively defeated by the Sioux and Cheyenne Nations.

The “Last Stand” narrative that paints Gen. Custer as a martyr to progress is written through the lens of settler-colonial propaganda and seeks to absolve him of the violent campaigns of suppression against Native peoples simply for existing on their ancestral lands.

Sitting Bull did not personally fight in the battle, but it was won under his spiritual guidance. It would be his last great victory, and one that gave hope to the Indigenous peoples across the country.

In this setting that reverberates with the ghosts of Indigenous genocide, the federal government enacted a second period of forced migration and detention when it converted Fort Lincoln into an alien isolation center in the early months of WWII. The prison was first used to hold some 1,100 Issei men arrested under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, who were detained at the site while awaiting their loyalty hearings.

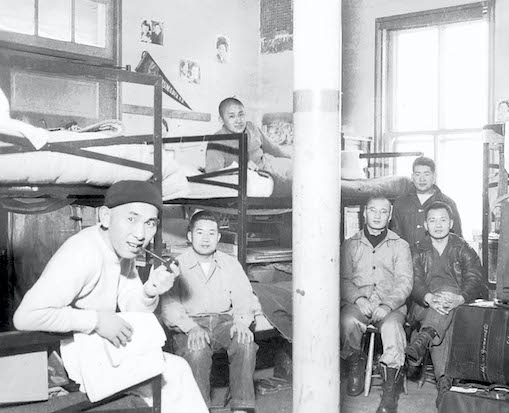

Fort Lincoln Internment Camp Japanese American incarcerees during World War II

Later in the war, 750 mostly Nisei renunciants were transferred from Tule Lake. Some were deported to Japan, and others were transferred to detention sites administered by the Department of Justice, such as Crystal City in Texas.

Fort Lincoln Internment Camp fence guard towers

Photos: Courtesy of UTTC

Among descendants of the incarcerees formerly held at this site, it has become colloquially known as the Snow Country Prison — so named by Itaru Ina in a haiku poem he wrote in late 1945. The untitled poem reads, “The war has ended / but I’m still in / the snow country prison.”

Yet, as much suffering took place in these territories, the United Tribes have transformed the former site of trauma into something positive, having successfully recovered a portion of their land with the establishment of the United Tribes Technical College in 1969. As the late former college president David M. Gipp jokingly said, “The Indians have finally taken Fort Lincoln.”

In visiting the college and interacting with the students and faculty, what stuck out to me was the profound sense of empathy shared by the Native communities. This sentiment was both immediate and universally felt by all with whom who we interacted.

Whether current college students in their late teens to early 20s or tribal elders in their post-retirement years, everyone we met welcomed us as friends and relatives. They understood implicitly the impact of generational trauma related to our shared histories of displacement, confinement and forced assimilation.

Speaking to this, the current college president Dr. Leander McDonald reflected on the many direct parallels in his remarks given at the opening ceremony of the memorial.

Dr. Leander McDonald speaks at the dedication ceremony.

“There’s been centuries of U.S. policy that forcibly removed Indigenous nations from their ancestral lands, especially the Land Removal Act of 1830,” McDonald said. “Many were confined to reservations, faced massive loss of territory and sovereignty. For Japanese Americans in WWII, Executive Order 9066 led to their uprooting. They were forced to abandon their homes, businesses and communities to live in internment camps. In both cases, U.S. authorities exercised a paternalistic rationale, justifying forced relocation as protective or necessary, despite being rooted in racial and cultural prejudice.”

Commenting on the specific conditions of confinement and their lasting impact on both communities, McDonald continued, “For Native Americans, reservations and boarding schools were deemed civilizing or protected, but actually reflected colonial control and assimilation. Boarding schools enforced English language and Christian practices, actively suppressing tribal languages and cultural traditions. This was a deliberate policy of cultural assimilation.

“For Japanese Americans,” he further continued, “their removal is framed as a wartime necessity, despite no credible evidence of threat. . . . Both of these experiences were rooted in systemic racism. For Native Americans, generations continue to bear the psychological and cultural wounds of displacement, boarding schools and loss of autonomy. Japanese American survivors and descendants experience lasting trauma, higher range of posttraumatic stress disorder, health issues, shortened lifespans and emotional scars.”

Further emphasizing the connections across our communities, the opening ceremony featured drum performances from TaikoArts Midwest and the Sloughfoot Singers. At one point toward the end of the ceremony, the two groups joined together for an ensemble performance that incorporated both taiko and drum circle traditions.

Seattle JACL’s Stan Shikuma places his offering on the memorial wall.

Photo: Rob Buscher

Pilgrims were then invited to pay their respects by affixing origami cranes with the names of formerly incarcerated ancestors onto the memorial wall. Some of the Native participants also placed into the wall’s alcove sage smudge sticks, used for spiritual cleansing to remove negative energy and commune with the spirit world.

An original crane offering left by a pilgrim

As pilgrims gave their offerings and prayers, a flute duet was performed by Megan Chao Smith on a Japanese shinobue and Dakota Goodhouse on the traditional Lakota-style flute.

The opening ceremony also featured a poem written by Dr. Denise Lajimodiere, the first Native American poet laureate of North Dakota. Incorporating some of Itaru Ina’s words into her verses, the final passage read, “A sunny, early fall day, a healing ceremony was held for Japanese internment survivors, while wiping away the tears, ceremony, smudging, prayers, song, the drums sang out across the field, the buildings that once held prisoners surrounded by barbed wire. Now, survivors are surrounded by a healing song, as each is wrapped in a star blanket, signifying safety, protection, warmth. Something healing is happening in North Dakota.”

Satsuki Ina remarked during the memorial ceremony that the creation of this memorial is perhaps the greatest enactment of solidarity that any community has ever shown Japanese Americans.

She commented, “When Dr. McDonald and others from United Tribes invited us to fill this space on land where they were going to memorialize our histories together, I actually cried when that invitation was made, thinking about the loss of land that the Native American people have suffered and yet so generously offering us this moment, this place and the heart of community.”

The entrance to Fort Lincoln then and now (Photos: UTTC and Rob Buscher)

Gifting our community space to erect a permanent memorial is the ultimate testament to the compassionate witness of our wartime incarceration by these Native Americans in North Dakota. Their allyship comes from the shared understanding of cultural genocide and erasure under white supremacist settler-colonialism.

Let us honor their gift by further educating ourselves about the history of Native Americans and acknowledge the role that our own community has played in settler-colonialism. In doing so, we can prove ourselves worthy of their trust and friendship as we fight together for our collective liberation.

To learn more about the Snow Country Prison Memorial, visit: www.uttc.edu/about-uttc/visit-our-campus/snow-country-prison-memorial-at-bismarck/.