By JACL Members Naoko Fujii, Esq; Daniel Mayeda, Esq; Larry Oda; Matthew Marumoto; and Mike Honda

The Japanese American Citizens League, joined by over 60 Japanese and Asian American organizations, filed an amicus brief in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on June 3. The brief challenges the federal government’s use of the Alien Enemies Act — an 18th-century law — now being invoked to justify the deportation of Venezuelan nationals.

Pictured are Alien Enemies Act Descendants (from left) Brian Shibayama, Anne Oda, Victor Uno, Mike Honda, Sharon Uyeda, Larry Oda, Bekki Shibayama and Naoko Fujii.

The Alien Enemies Act has a troubling history. During World War II, the statute was used to detain Japanese immigrants in Department of Justice and military-run prisons, separate from the 10 War Relocation Authority camps where over 120,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated. Among those targeted were Buddhist priests, Judo instructors and respected community leaders — not because of any proven wrongdoing, but because of their roles as leaders within the Japanese American community.

A Congressional commission later found that these mass incarcerations were not driven by military necessity, but by “war hysteria, racial prejudice and a failure of political leadership.” That conclusion, once assigned to a past era, now holds renewed relevance.

For the JACL, the parallels between the government’s treatment of Venezuelan immigrants today and the experiences of Japanese Americans during WWII are unmistakable — and deeply personal.

JACL members including Naoko Fujii, Daniel Mayeda and Larry Oda all had parents or grandparents arrested under the Alien Enemies Act in the days following the attack on Pearl Harbor. Taken by the FBI without notice, denied legal representation or the right to contact family, they were held in jails and later transferred to “enemy alien” detention camps — often for longer durations than family members incarcerated under Executive Order 9066.

Now, more than 80 years later, the Alien Enemies Act is again at the center of legal controversy. The Trump administration has used the statute to deport Venezuelan nationals to detention in El Salvador, alleging — without presenting clear evidence — ties to the Tren de Aragua gang. Legal scholars and civil rights advocates argue that the government’s rationale mirrors the flawed reasoning used against Japanese Americans: The absence of evidence is itself evidence of danger.

In a recent case before the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas, a federal judge rejected the government’s arguments, citing “shoddy affidavits and contradictory testimony.” The court concluded that the evidence presented would not withstand scrutiny in even the smallest lawsuit, “let alone what is at stake here.”

The JACL’s decision to act was grounded in a collective memory of injustice. “We couldn’t keep quiet,” said Fujii, who led the JACL amicus brief team. “If we don’t speak up, this law — used against our families — will continue to be used to discriminate based on nationality and fear, not facts.”

The brief, prepared by pro bono counsel from the Asian Law Caucus, Asian Americans Advancing Justice | AAJC and the Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality, draws a direct line from current executive overreach to historical civil liberties violations. It references the infamous Korematsu decision, in which the Supreme Court upheld Japanese American incarceration during WWII. In his dissent, Justice Murphy warned against judging individuals by ancestry rather than actions, while Justice Jackson cautioned that the Court’s decision had created “a loaded weapon ready for the hand of any authority.”

That weapon, the brief argues, is now in use once again.

The Executive Branch is exercising broad powers to detain and deport immigrants, often without the due process protections guaranteed by the Constitution. Courts, reluctant to interfere, have deferred to executive discretion. What makes this moment particularly alarming is how easily long-standing laws are being distorted to serve political ends.

The historical parallels are stark. In 1930s Germany, authoritarianism advanced through the targeting of marginalized communities, the silencing of dissent and the erosion of the rule of law. While the United States is not yet in such a state, the trajectory is unsettling. It often begins with a statute reactivated, a right revoked, a group scapegoated.

Japanese Americans know the cost of silence. Far too few other Americans stood up to object as thousands of Japanese Americans were stripped of their civil liberties, their livelihoods and their dignity. Even after WWII, it took over half a century for Japanese Americans to achieve redress for wartime incarceration; the Japanese Latin Americans are still fighting for redress and reparations. That legacy compels the community to speak out when new groups are targeted based on xenophobia and fear.

Unlike the wartime “enemy,” the threat today is artificially constructed — ordinary migration reframed as an invasion. Fear, once again, is being deployed as a political tool, and it is easier to target those who look different.

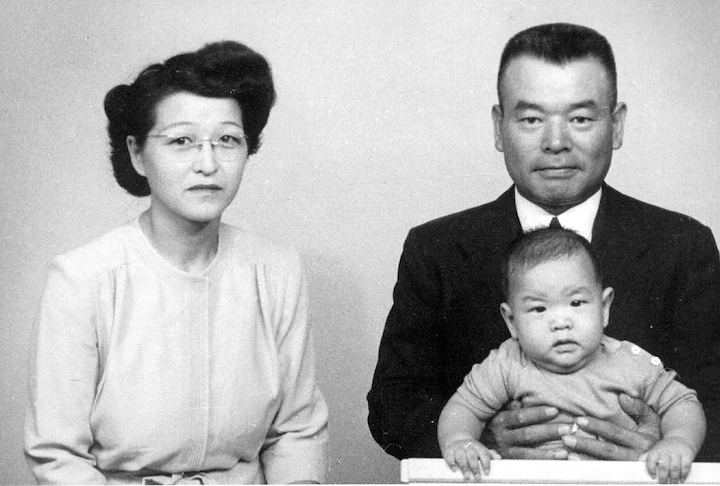

The Oda family: Maki Lorraine, Junichi and Larry Oda (seated on his father’s lap)

JACL National President Larry Oda’s personal story appears in the brief. His father, Junichi, was a hardworking businessman who helped lead Monterey’s abalone processing cooperative. Active in the Japanese Businessmen’s Assn. and a donor to the Japanese Red Cross, Junichi Oda had lived legally in the U.S. for 25 years. Nonetheless, at age 41, he was arrested without notice, labeled an “enemy alien” and detained in a succession of government facilities, including the Santa Fe and Lordsburg internment camps. He was later reunited with his family at Crystal City, where Larry was born.

Junichi Oda’s story is not unique. Beginning Dec. 7, 1941 — before EO 9066 — the government used Presidential Proclamation 2525, issued under the Alien Enemies Act, to arrest more than 17,000 Japanese and Japanese Latin Americans. Many had lived in the U.S. for decades but were ineligible for citizenship due to racial restrictions in federal naturalization laws.

Former Congressman Mike Honda has long warned of the dangers posed by the Alien Enemies Act. “This is not a partisan issue — it is a Japanese American issue,” Honda said. “This is a call to action for all Japanese Americans: Engage your local school boards, county supervisors, state legislators and congressional representatives to pass resolutions supporting the Neighbors Not Enemies Act, which would repeal the Alien Enemies Act.”

The proposed legislation — S.193 in the Senate and HR 630 in the House — is co-sponsored by Sen. Mazie Hirono (D-Hawaii) and Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn, Fifth District).

Under Executive Director David Inoue’s leadership, the policy team has submitted testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee, led grassroots lobbying efforts, created public action alerts and trained advocates through programs like the 2025 JACL/OCA Leadership Summit.

The law, first passed in 1798, was last used during WWII. Critics argue that its use now is a legal shortcut — an effort to bypass the due process required under modern immigration law.

“If we don’t tell these stories, no one will know this happened to us,” said Larry Oda. “And we can’t let it happen again.”

To read the authors’ and more stories, visit the Alien Enemies Act Stories Project at: https://jacl.org/alien-enemies-act-stories.